Remember the CrowdStrike reboot debacle back in 2024?

The company created a new detection signature (a data-only update) for its malware-spotting product, and pushed it out to all its users.

That’s often considered a low-risk kind of update, because the program code itself hasn’t changed, and no new software features have been added.

Except that CrowdStrike tried to cram a 21st data chunk into a block of memory that was designed to hold just 20 such signatures, creating a buffer overflow, as the jargon calls it.

This crashed the product component concerned, which just happened to be a kernel driver, buried right down in the operating system layer of Windows itself, and the only truly safe way out when the operating system itself gets corrupted is to “blue screen” and reboot afresh.

You can either imagine or remember what happened next.

Even though CrowdStrike updated the rogue update within two hours, afflicted computers typically crashed again so soon after rebooting that the product’s auto-update software never got a chance to run and fix the problem, so the computer rebooted again, and crashed again, and․․․

․․․ended up stuck in a bootloop, until either someone knowledgeable intervened and fixed the issue by hand, or the user got lucky and after umpteen fruitless reboots, the updater finally managed to run before the buggy driver crashed, and thereby corrected the fault by itself.

The should-I-or-shouldn’t-I dilemma is the primary concern that most people have when updates come out, especially if they’re cybersecurity-related patches and the consequence of not updating is to fall behind on safety and security.

What if you don’t patch, and thus end up in the very group of users on whom cybercriminals and state-sponsored attackers will tend to focus their attention, especially if they figure out how to exploit the now-known bugs you haven’t fixed?

But what if you do patch, and your computer either doesn’t work properly afterwards or, as in the extreme case of CrowdStrike’s buffer overflow, won’t reboot at all?

With that in mind, Microsoft’s recent patch-for-a-buggy-patch update, dubbed KB5077797, makes an interesting change from the usual tales of woe.

In this case, the Patch Tuesday updates for January 2026, which came out as usual on the second Tuesday of the month (2026-01-13), introduced a bug that for some users meant that although they could still start up their computer just fine after applying the fixes․․․

․․․they couldn’t always shut down correctly in the first place!

To be clear, this comedy of errors didn’t create the same sort of outages and disruption as the abovementioned CrowdStrike incident, not least because “stuck” computers would boot up again OK if they were forcibly shut down.

Today’s laptops, almost without exception, include a fail-safe power-off option, whereby holding down the power button for five seconds (or longer – mine has a 10-second delay) deliberately and abruptly cuts off the power and leaves the computer off until it’s manually turned back on by pressing and holding the button again for a second or two.

A forcible shutdown of this sort doesn’t depend on the co-operation of the operating system, or on any special software you’ve installed, so it works even if the operating system has crashed and the computer is frozen.

The old-school trick of force-closing a desktop computer by yanking out the power cord (by design or inadvertently) doesn’t work with a laptop unless the battery is discharged or dead, so holding down the power button for long enough that you’re unlikely to do it by mistake is the emergency compromise.

Sudden shutdowns aren’t the best thing in the world, but these days they very rarely cause the sort of system corruption that leaves your computer unable to bootup at all, as the less security-conscious operating systems of yesteryear sometimes did, so they’re acceptable from time to time if you have no other choice.

Of course, this bug isn’t entirely without risks.

Although hard-stops using the power button are usually OK, and generally don’t result in an unbootable computer, they can leave you with lost data that was still in memory and never saved, with corrupted files that some fussy applications might refuse to load in future, or with an extended reboot time caused by automated operating system safety checks.

There’s also another worrying issue, especially if you live in the Southern hemisphere, where it’s midsummer right now, namely that this bug means that you might think your computer has shut down, or entered a low-power state such as sleep mode or hibernation, when it hasn’t.

And if it hasn’t, but you blithely put it into its protective case, shove it into your backpack, and set off for a bicycle ride home from a coffee shop in summer temperatures of more than 310K (about 40°C, 105°F, or 565°Ra), then – and don’t ask me how I know this, though I got away with it at the time – you may end up with an overheating crisis when you reach your destination.

If you’re lucky, the battery will go flat before there’s a meltdown, or your laptop will have temperature sensors that shut it down even if the operating system has already crashed; if not, you could end up with a damaged computer.

My laptop did shut itself off in time, so I avoided catastrophe, but I had a lengthy wait before I could use it again. Resist the temptation to put an overheated computing device in the freezer to speed up the cooling process. When you take it out, moisture in the air will condense or freeze onto it, inside and out, and potentially (pun intended) leave you with a whole new problem if you turn it back on before it’s dried out.

Amusingly, if that’s the right word, this bug was caused by a Windows security feature that’s supposed to provide extra protection for your computer when it’s in the most vulnerable part of its bootup process.

That’s the time between the firmware that’s baked into the computer by the manufacturer, and the operating system you’ll finally be running.

The firmware is supposed to be cryptographically protected by the vendor, so you can’t, by default at least, replace it with your own low-level code; and the operating system partition is these days usually protected with a full-disk encryption toolkit such as BitLocker (Microsoft Windows), FileVault (Apple macOS), LUKS (Linux), or GELI (FreeBSD).

But between the locked-down firmware and the encrypted operating system, which enforces its own security controls once it starts up, come one or more UEFI applications that help the operating system itself to load up.

UEFI is short for Universal Extensible Firmware Interface, and presents a low-level set of software functions that boot-time programs and drivers can call upon.

This is a modern-day replacement for what used to be the BIOS, a much less structured and freewheeling boot-time layer known as the Basic Input/Output System that Windows no longer uses on hard disks.

Make no mistake: UEFI is a sprawling coding landscape, implemented in the C programming language and aimed squarely at C programmers.

It has none of the user separation and memory-based protection that higher-level operating systems provide, and gives programmers plenty of opportunity for coding in security vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows and memory management bugs.

But UEFI has several advantages over the old-style BIOS approach, including that it is at least consistent and extensively documented (for all that the documentation can be complex and confusing), and that it supports a system known as Secure Boot.

When turned on, Secure Boot means, in theory at least, that only digitally-signed UEFI applications and drivers can take part in the bootup stage between the firmware and the operating system.

(UEFI apps use the same internal structure as Microsoft Windows programs, but they can’t run in Windows, and by convention have the extension .EFI instead of .EXE.)

The idea is that, even though these UEFI apps live in an unprotected FAT-based partition (Volume 3 in the image below) where anyone with temporary access to your computer can modify them easily, unauthorized or unwanted tampering will fail because the modified files won’t be correctly signed.

If there is a downside to Secure Boot, it’s that it is cryptographically dominated by Microsoft, so that digitally-signed UEFI applications almost always need a chain of signatures signed off by Microsoft itself.

Unlike web-style digital signatures, you don’t get a range of trusted certification authorities, including not-for-profit ones, to choose from.

Of course, if you’re planning on running Windows 11 anyway, Secure Boot is required, should “just work,” and has certainly made dangerous pre-boot malware such as rootkits and bootkits much harder for attackers to deploy.

But even a UEFI-based bootup that’s protected by Secure Boot isn’t perfectly secure, not least because bug-free UEFI apps are hard and expensive to write.

Here’s a short video from 2025 showing a proof-of-concept attack against Microsoft’s own UEFI bootloader code, exploiting an old vulnerability by reinjecting a buggy UEFI app, even though it had been patched some time before:

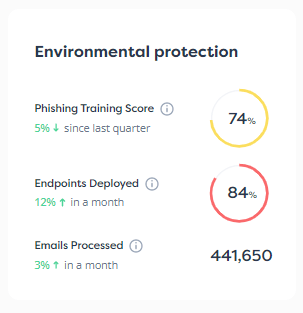

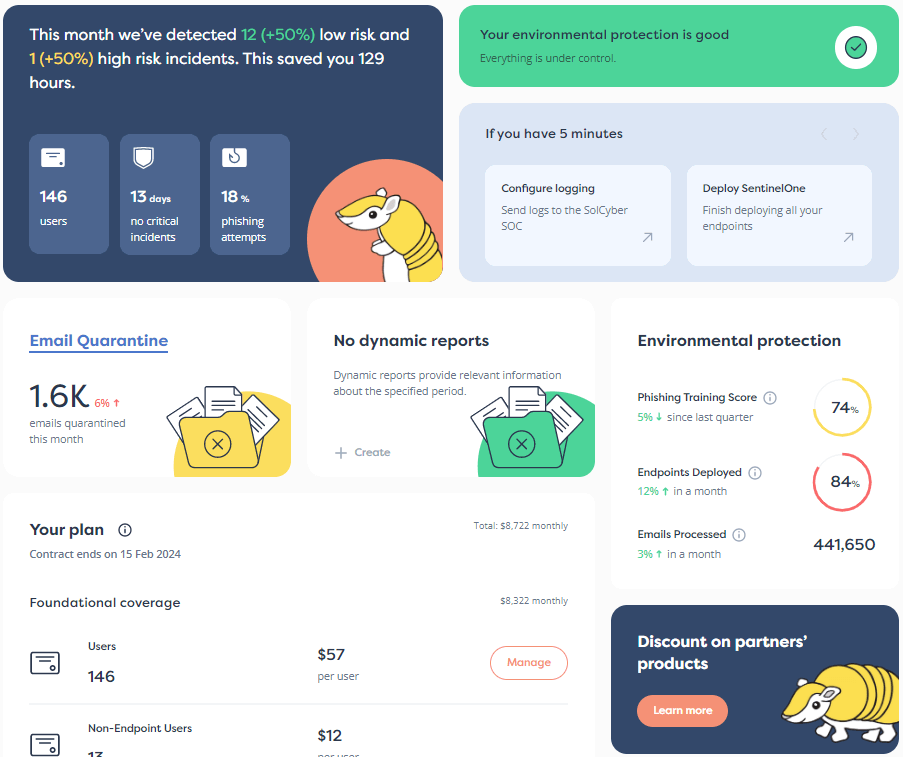

For more fun visual content of this sort, including the delightful explainer series Amos The Armadillo’s Almanac, why not follow @SolCyber on LinkedIn?

Additionally, UEFI drivers and apps sit quietly and apparently unimportantly in a disk partition that many people rarely look at, or don’t even know about. (See image above for how to inspect the EFI partition, which isn’t accessible via the conventional Disk Management program.)

Although these apps are vital for booting up your computer, they directly generate neither much interest nor any revenue, so they often fly under the the radar of scrutiny and patching, for vendors and users alike.

Windows 11 therefore includes yet another layer of protection for the UEFI environment, based on the same sort of virtualization technology used by popular software such as Hyper-V, Xen, and KVM.

This protection is known as System Guard, and its goal is to prevent unexpected and unauthorized fiddling with the system firmware once the system is running, even by users with admin-level powers.

It also provides additional protection during startup against malicious UEFI apps, even ones that are digitally signed or that know how to exploit vulnerabilities that can sidestep Secure Boot’s security checks.

Unfortunately, System Guard turned out to be a sort-of back-to-front Achilles’ heel that caused the bug now fixed by KB5077797.

Unlike Achilles’ famous heel, which was his one and only weak spot, this vulnerability was pretty much that the System Guard protection turned out to have an overly strong spot that prevented legitimate activity introduced into Windows after the January 2026 Patch Tuesday update!

If you’re vulnerable, you should have received KB5077797 by now via Windows Update.

You can check by looking at your update history on the Settings > Windows Update page.

If you don’t see KB5077797, then force an update manually, which should either fetch the patch if it applies to you, or complete successfully without reporting KB5077797 if you don’t need it, as seen in this example:

Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.