What sort of data collection is “fair and reasonable” when it’s your car doing the collecting?

The James Bond film Goldfinger, starring Sean Connery as 007, the world’s most public secret agent, was released in 1964.

Bond’s spy tools in the film included, as usual, a tricked-out sports car.

This one was an Aston Martin DB5 fixed-head coupe featuring an amazing array of armaments and accessories that could only exist in a Hollywood fantasy.

The car had revolving vehicle tags – British, French and Swiss – that were “valid in all countries,” twin Browning machine guns, tire slashers, an oil-slick generator, a smokescreen system, and even a passenger ejector seat, triggered by a hidden red button under a flap on the gear-shift knob.

But these add-ons were not not the most outlandish or unbelievable features of the vehicle.

After all, world leaders had used cars fitted with bulletproof glass for years.

The famous Willy’s Jeep of the 1940s was actually based on an unassuming automobile engine and readily-available transmission components, yet sported a .30″ (or even a .50″) Browning, just like Bond’s DB5.

And aircraft cockpits just as cramped as an Aston Martin cabin had been fitted with ejector seats since the 1920s, and these became standard in military jets from the late 1940s.

Without doubt, the most jaw-dropping ‘I want one of those!’ technological features in the Goldfinger movie were the tracking and navigation devices.

As Q explains when he shows the gadgets to Bond:

“Here’s a nice little transmitting device [smaller than a pack of cards] called a ‘homer’… The smaller model [smaller than a USB key] is now standard field issue. It will be fitted into the heel of your shoe. Its larger brother is magnetic, to be concealed in the car you’re trailing while you keep out of sight. Reception is on the dashboard [behind a fake ventilation grille].. Audio-visual, range 150 miles.”

In the movie, the audio-visual tracking isn’t just a basic oscilloscope with green blips on a black background, but a detailed moving map with roads and topographic detail – better than a top-notch modern vehicle navigation system, in fact.

Unfeasible at the time, but just the thing for an over-the-top spy movie from the heady 1960s era.

Who wouldn’t want one?

Sixty years later, however, in-car navigation is something you’ll find in many private vehicles, even entry-level models.

So important is precise geolocation that there are now four globally available and entirely independent satellite-based positioning systems: GPS (run by the USA), GLONASS (Russian), Galileo (EU) and BeiDou (China), all of which work on a similar principle based on location devices that listen for precise time signals broadcast by an array of 20 or 30 satellites.

Those positioning devices therefore only need to receive data, not to transmit any replies or acknowledgments.

This means, in theory at least, that portable positioning devices, which are tinier even than the ‘heel of your shoe’ tracker that Q shows to Bond in Goldfinger, aren’t enough on their own to give you away to other people.

With GPS, BeiDou, GLONASS and Galileo, you know where you are, with astonishing precision: even the smallest and cheapest bicycle head units, weighing just 25 grams (less than an ounce), are accurate enough to show where you changed lanes or moved out to pass a parked car.

But they don’t know where your receiver is, or even that it is listening out for their positioning broadcasts.

With the receive-but-don’t-reply nature of GPS and its cousins in mind, it’s easy to assume that the so-called ‘connected car’ of today works entirely to your advantage, with no immediate risk to the privacy of your location, the places you’ve visited, or the route you took to get there.

However, and this is a huge however, very few contemporary location and navigation units are true ‘receive only’ devices.

Even those 25g bicycle navigation units can hook up to nearby devices wirelessly, in case you want to share your ride live, in real time, which surprisingly many people do.

(The head unit doesn’t need the oomph to reach a GPS satellite or even the nearest cellphone tower: it talks to an app on your phone, which goes online on its behalf, leaving you free to pack your phone away safely in a padded bag, out of the rain and protected from crash damage.)

Connected cars, of course, do much, much more than that.

Firstly, they have access to the car’s own electrical supply, so they can stay connected and active as long as they like.

Secondly, cars collect much, much more data about every aspect of your journeys than any hiker’s or cyclist’s trip computer.

A modern car typically collects, records, and may – either in real-time or at some future point when you ‘sync’ or ‘update’ via the car’s menu or its associated phone app – upload into the cloud a plethora of details, which could include:

Additionally, the car’s network has access to data that you sync with the vehicle from connected devices such as mobile phones, tablets, music players, Bluetooth gadgets, and more.

Your contact list, your list of made and received phone calls, your text messages, the music tracks you listened to, the videos your kids have watched along the way: those will on be on the list of potentially visible lifestyle information revealed to the vehicle.

Your car doesn’t just know that you went shopping.

It knows (or could know, for all you know) which mall you went to, how many people set out with with you, how you got there, and whom you picked up or dropped off along the way (their phones or Bluetooth devices would give them away entering or leaving the vehicle, even if none of the in-car sensors did).

It could tell what radio show you listened to on the journey, what you talked about, whom you called while you were in the car park, how much gasoline or electric charge you bought while you were out, and whether you drove with the aircon on or rolled the windows down instead.

It knows how many times you changed lane without signaling, whether you made any reckless left or right turns that chirped the tires, and how many other drivers made you angry along the way.

It certainly knows just how vigorously you put your right foot down when that burbling 1969 Mustang pulled up next to you at the lights, and just how hard you had to brake when you ran out of room for your impromptu street race.

As the Mozilla Foundation put it in an article published about a year ago:

There’s probably no other product that can collect as much information about what you do, where you go, what you say, and even how you move your body (“gestures”) than your car. And that’s an opportunity that ever-industrious car-makers aren’t letting go to waste. Buckle up. From your philosophical beliefs to recordings of your voice, your car can collect a whole lotta information about you.

Of course, the data that gets collected and uploaded isn’t all that matters: there’s the thorny problem of who gets to see it, including data brokers and third parties who might get a chance to buy it up, mine it, and perhaps to sell it on again.

Australian non-profit and consumer advocacy group CHOICE recently looked at this issue in a study that looked for the devil-in-the details of the privacy policies of 10 popular automotive brands.

The Australian public broadcaster ABC wrote up an article about the findings that bluntly announced: “These car brands are collecting and sharing your data with third parties.”

The article’s summary put it like this:

In short: An investigation by consumer advocacy group CHOICE found most of Australia’s popular car brands collect and share “driver data”, ranging from braking patterns to video footage.

Kia and Hyundai collect voice recognition data from inside their cars and sell it to an artificial intelligence software training company.

What’s next? Privacy and consumer rights advocates are pushing for law reform to limit data collection to what is “fair and reasonable”.

.

The problem identified by CHOICE wasn’t so much that data was being collected, which all of us probably realize, but the difficulty of finding out what privacy policies drivers had agreed to in the process of purchasing a vehicle.

Buying a vehicle often involves lots of paperwork such as finance and insurance, matters that undoubtedly dominate the concerns of most buyers.

In comparison, the issue of whether they are selling off their drivetime playlists to advertisers, or helping AI companies make their voice prompts better, hardly seems important.

Unfortunately, one of the big takeaways from the CHOICE study is just how different the privacy policies, the opt-in-and-out procedures, and the available data deletion tools are from manufacturer to manufacturer and even from model to model.

That’s troublesome, because it means there’s no simple way for any cybersecurity advisor or privacy expert to provide a ‘one size fits all’, or even a ‘one size fits many’ list of where to look, what choices to make, and what buttons to press in the app or in the car itself to tailor your privacy settings to your liking.

To be clear, cars that send and receive real-time vehicle and journey data aren’t all bad.

Satnav means you’re less likely to get lost or to try to read a printed map while negotiating unfamiliar roads, real-time traffic updates mean you’re more likely to avoid jams and thus reduce congestion and pollution, and automated detection of potential emergencies makes it more likely you’ll get help if you break down in a dangerous location or get into an accident.

Similarly, vehicle and video data that you willingly decide to share with an insurance company could reduce your premiums, and help settle disputes quickly and more equitably after a collision.

Nevertheless, data about you, your driving, your family, and your friends shouldn’t be something that gets collected at all, let alone monetized, until you have given explicit consent, clearly requested and properly explained.

Until that is the norm, all we can really offer are the following very general tips:

Consumer opinion does matter, and consumer privacy choices can change things for the better!

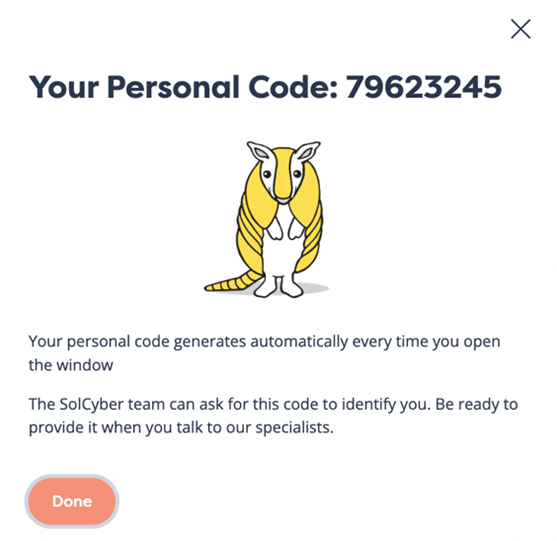

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.