Clouds are made of water droplets bobbing around in the sky, so it’s unusual to think of them on fire.

Unless they’re clouds of smoke billowing from burning data, of course.

Intriguingly, the Old English word for cloud was wolcen (plural wolcnu), like the words still used today in other Germanic languages such as Dutch (wolk/wolken) and German itself (wolke/wolken).

But somewhere along the line, it seems that the related word clud/cludas, as in today’s word ‘clod’ meaning a rounded lump of stone or earth, became associated metaphorically with the ‘lumps’ formed by wolcnu in the heofon above․.․

․.․and thus we came to the phrase ‘clouds in the sky’, which was eventually adopted in turn as a visual metaphor used to simplify the depiction of the mass of ethereal interconnections (pun intended) in a modern computer network.

And that metaphor was itself extended to refer to the actual servers in the server rooms, too, which we now call data centers, because they’re generally much roomier than a typical room these days.

And that metaphor was then extruded in turn to include the network and all other computers involved except our own desktop or laptop, so we no longer needed network diagrams at all.

The wireless routers, the cabling, the fibre, the firewalls, the switches, the racks, the servers, and their many hard disks, just became part of ‘the cloud’, and there was rarely any need to depict it diagrammatically when we could just assume it.

The modern cloud, therefore, is both transient and vaporous (as wolcnu are), and solid (as cludas, buildings, servers, and disks are).

Computing clouds can metaphorically dissipate, if the network has an outage, or literally burn down, if the data center catches fire.

Sadly, the latter is what happened late last month to a substantial governmental cloud service in South Korea.

Reports suggest that, in the conflagration, close to one petabyte of data went up quite literally in clouds of smoke.

The amount of data involved was such that the cloud service, to put it simply, was used for both the data and its backups, given that the compelling reason for using a cloud-style service in the first place was the difficulty of arranging a petabyte of storage anywhere else.

Ironically, it seems that the fire was caused by lithium batteries, presumably present in the data centre to provide backup power to keep the system going if the electrical grid failed.

Lithium batteries hold so much energy for their volume that they are notoriously unpredictable if they overcharge and overheat, and spectacularly hard to extinguish if they ignite.

Don’t fall into this trap with your own data, whether at home or in a small business.

Remember the saying 3-2-1․.․

Aim for three copies (live and two backups), using two different storage systems, ideally with one of them stored both offsite and offline.

Offsite so that if one copy catches fire, the other doesn’t; offline so that if one copy gets breached and ransomed remotely by cyber criminals, the other doesn’t.

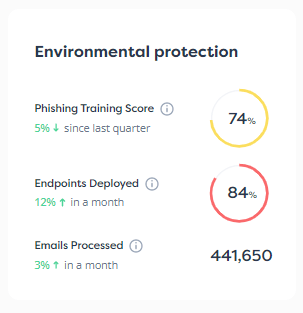

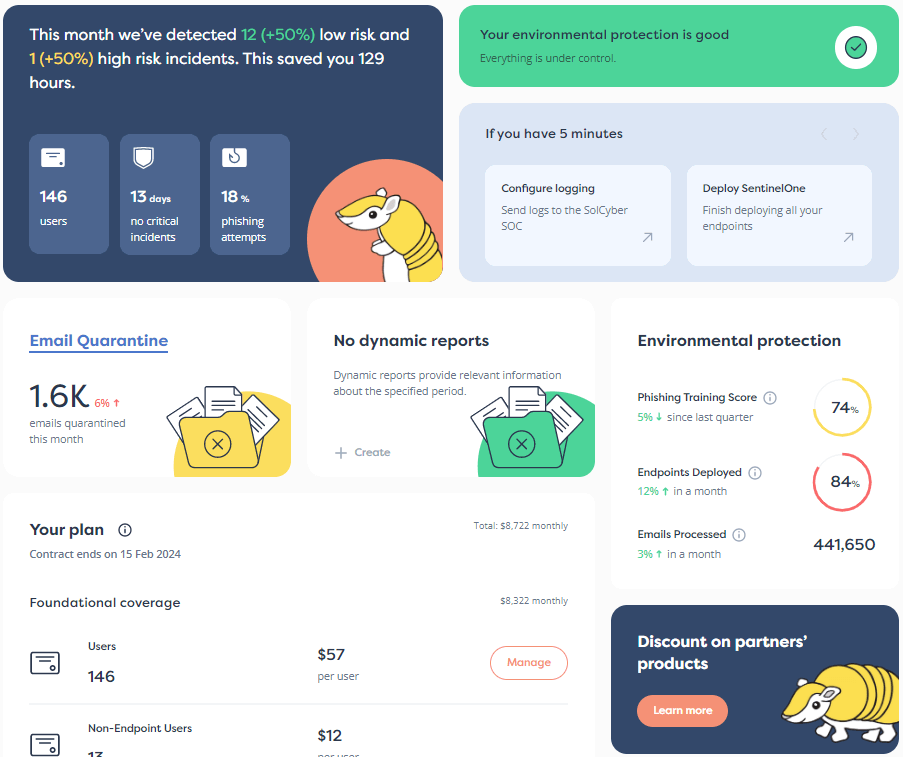

Need to review your backup policies? Need to review your procedures? Struggling to stay afloat in the midst of all those cybersecurity tasks and tools? Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of fire and flames by Christopher Burns (really!) via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.