Cybersecurity is awash with acronyms, which certainly saves lots of space in marketing material and adds a certain high-falutin aura to sales patter.

But this tendency comes without a mixture of complication and controversy.

Ironically, part of the controversy is that language purists insist that abbreviations are initialisms and not acronyms unless they can be pronounced as words, so that all acronyms are initalisms, but not all initialisms are acronyms.

The complication comes in the form of confusion, where the phrase that the letters stand for gets superseded or forgotten altogether, but the initialism nevertheless enters widespread usage as an item of vocabulary that is taken for granted, even though no one is really sure quite what it means any more.

MDM, short for mobile device management, is a fascinating example.

When this terminology first became widespread, the word “mobile” generally implied the phrase “mobile phone”, in the sense of a smartphone of the iOS and Android sort.

Not merely a traditional cellphone or feature-phone, but a handheld computing device that could be used as a a phone, yet that was more of tiny, truly mobile computer with a broad choice of apps for consumers and companies alike.

By the time Apple and Google phones arrived on the market, the word “endpoint” was already in widespread use, typically as an umbrella term to describe regular computers that weren’t servers, thus avoiding the cumbersome phrase desktop, laptop or notebook.

And by the early years of the 2010s, cybersecurity software for these endpoints acquired its very own initialism EDR, short for endpoint detection and response.

Most vendors adopted the tag EDR very quickly, because any product that still billed itself as an “anti-malware” or “anti-virus” sounded pale in comparison, and didn’t match the fancier name now being used by analysts for software that, after all, did much more than merely scan for computer viruses.

There was a modest problem, however, in applying the name EDR to third-party security products designed for mobile phones and their tablet-sized counterparts.

Many mobile security toolkits could detect some malware, prevent some types of malevolent behaviour such as snooping on other apps, and delete rogue text messages before they could cause trouble…

…but both Apple and Google (and, briefly, Microsoft with its Windows Phone product, discontinued in 2015) exerted considerable control over third-party software vendors, notably making it somewhere between difficult and impossible for cybersecurity vendors to produce and maintain full-strength EDR tools for mobile phones.

Apple notoriously, right from the first version of iOS, implemented rigid controls, not only locking down the operating system itself against modification or repurposing by anyone else, even the device’s owner, but also limiting the apps available for download to an App Store owned and operated by Apple itself.

Google’s own Android phones have generally been more flexible, in that most of the company’s own devices can be wiped and reflashed with an operating system of the owner’s choice, including a free, non-Google-branded build of Android such as LineageOS, and can be configured to accept “off-market” downloads that don’t come from the Google Play Store.

Nevertheless, Google Android itself doesn’t let independent cybersecurity software vendors do everything they might want or need: as in Apple’s iOS, there are strict built-in controls over how apps interact.

Notably, every app runs as a different user, so that apps can’t access each other’s data by default, or peek at each other’s on-screen data, or interact in any of the many ways we expect and find useful on desktop or laptop computers.

From a cybersecurity point of view, that’s great for privacy and safety, because even a buggy or deliberately rogue app can’t inevitably snoop on what you are doing in your other apps.

But that sort of blanket restriction also makes cybersecurity innovation hard, because writing a low-level threat-blocking program when one app can’t keep its eye on others, even for respectable and useful purposes, limits its range and effectiveness.

Indeed, many vendors who used to offer EDR-style tools for Apple and Google phones have largely given up doing so, for two main reasons:

Fortunately for companies who are concerned about mobile phone security, both Apple and Google do provide built-in support for mobile device management tools.

MDM tends to focus on reducing what’s known in the jargon as the attack surface of devices used for company work, rather than detecting and blocking rogue behaviour when it does happen, for example by:

The trendy terms you will hear for phones that have been hacked to reduce security right down at the operating system level are rooting on Android, because root is the official name for the administrator account used by Android itself, and jailbreaking on iOS, a nod to the act of escaping from Apple’s carefully regulated ‘walled garden.’

Annoyingly, perhaps, Apple and Google have come up with rather different MDM systems and terminologies, so that users who switch from iPhone to Android or vice versa may find the other’s approach a little confusing at first.

Loosely speaking, Apple devices generally rely on a single copy of apps such as an email clients, accessing two different accounts, each with their own, separately managed data stores.

Google’s approach involves two separate profiles, each with their own full copy of every app required for work and personal use, each with their own apparently independent storage, almost as though you had two phones and kept swapping between them.

Google also allows more options for how much power the IT team or security operations center (SOC) have over individual devices.

If you haven’t come across these initialisms before, prepare to learn about:

Interestingly, Google has an MDM mode even stricter than Fully Managed, known as Dedicated, which is designed for kiosk-style devices such as bus stop signs or advertising hoardings, which can be used to keep the device locked into in a single app, preventing access to any other apps or even the home screen.

Apple’s approach is less granular.

Apple allows iPhones to be set up for what’s known as Zero-touch Enrolment, where the devices are bought by the company, pre-configured by a device distributor, and delivered as if truly new.

Users get all the delight of taking the product out of the box and peeling off the protective packaging as if it were their own, but get few or no choices in the setup process.

Alternatively, for users who want to use their own devices, Apple supports User Enrolment, which gives up less control and information to the IT team

For example, under Apple’s User Enrolment process:

Before we finish, we need to point out that although MDM started life as an alternative sort of cybersecurity toolkit for devices that didn’t or couldn’t enjoy the same levels of EDR protection as your laptop…

…its remit now extends, in Microsoft’s vocabulary at least, to laptops, desktops and even servers.

As mentioned above, Microsoft killed off its Windows Phone product nearly a decade ago, but still offers a set of products and services dubbed MDM, with operating system enrolment identifiers all the way from PRODUCT_HOME_BASIC, through PRODUCT_CONNECTED_CAR, to PRODUCT_ENTERPRISE_SERVER.

MDM seems a curious name for a cybersecurity product intended for use on systems such as Windows servers that you are probably already be protecting and managing with more powerful, broqder-brush tools such as EDR, inventory tracking, and directory services.

But it’s worth remembering, in Microsoft’s vocabulary at least, that the initialism MDM is used to refer to device management in general, whether that device truly is mobile or not.

Getting value out of MDM, instead of merely putting cost into it, generally requires compromise by both sides:

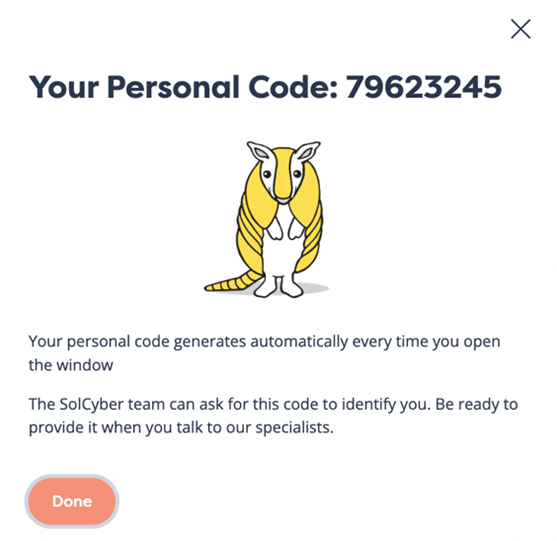

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of a mobile pbone by Ravi Sharma via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.