The word ransomware, in its original meaning, was coined close to 40 years ago, at the end of 1989.

At the time, malicious software, or malware, was already a significant cybersecurity problem , usually in the form of computer worms or viruses – self-spreading programs that copied themselves from computer to computer without permission, wreaking havoc along the way.

The damage caused by malware, even when the perpetrator was apparently just showing off and didn’t intend to cause real harm, could be serious.

But no one had figured out how to make money out of malware, because it wasn’t obvious how to trick or to coerce victims into paying up.

There were no online payment systems to hack or subvert back then, not least because only a minuscule percentage of users had access to a network.

Until a cybercriminal named Dr Joseph V. Popp from the US figured out a trick to “kidnap” your precious data virtually, in the hope of blackmailing you into paying for its safe “return.”

He created what looked like an interesting software utility, programmed it to lie low for a while so no one would raise the alarm as it implanted itself on PCs the world over, and then used it to scramble your data unexpectedly, right there in place on your own computer.

The software was snail-mailed out on floppy diskettes, so it required no modem or network for potential victims to download it in the first place, and it needed no network over which to “steal” their data (or exfiltrate it, to use one of the military metaphors that suffuse cybersecurity today).

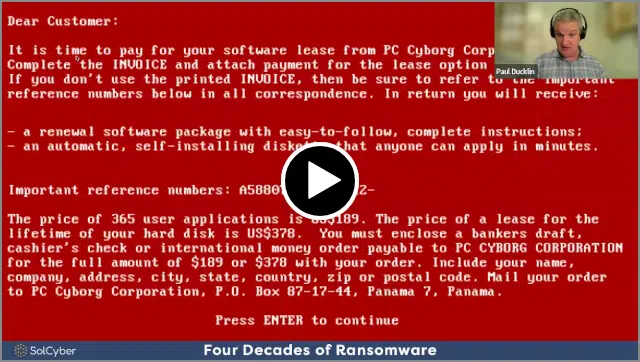

Once it triggered, the malware attempted to extort a ransom payment of $378 via money order to an accommodation address in Panama.

The software showed a bright red warning message that filled the screen, and even printed out the message in the form of an “invoice” if you had a printer attached.

You can also watch this video directly on YouTube if you would like additional video controls, including speed-up.

You can also watch this video directly on YouTube if you would like additional video controls, including speed-up.

If this MO sounds familiar, right down to the ransom note dumped to the printer and the dramatic red warning in the middle of the screen, that’s because cybercriminals are still using the same techniques today, sucking many hundreds of millions of dollars a year out of the global economy via blackmail payments just like Popp’s.

In case you’re wondering, Popp carefully avoided sending his malware to people in the US, presumably in the hope of keeping US law enforcement off his back. Many of his victims were subscribers to a UK computing magazine, from which he acquired a mailing list under false pretenses, so most of his victims were in Britain. Popp was extradited from the US to the UK to stand trial for cyberblackmail, but ultimately found mentally unfit and deported back to the US, where he died in 2007. With no prepaid credit cards or cryptocurrencies in those days, paying up was simply too hard, so the money-making part of the scam didn’t work out. Indeed, ransomware was rarely seen again until almost 25 years later, once pseudo-anonymous online payments had become possible.

Today’s ransomware criminals, of course, are much better organized and much more demanding that Popp was, because they tend to do some or all of the following:

For years, CISOs, users, lawyers and politicians have wrangled with the thorny problem of what to do about ransomware from a regulatory angle.

Clearly, the outright criminality of ransomware attacks has been established in many countries for many years, with numerous arrest warrants and criminal prosecutions brought against attackers, right back to the days of Joseph Popp himself.

But what about regulations that apply to those who fall victim to ransomware crimes and other cyberbreaches?

After all, if you have chosen to collect personal data from customers for your own commercial advantage, and assured them that their information will be closely and safely guarded․․․

․․․but then fail to live up to your promise, why should becoming a cybercrime victim exonerate you from liability or consequences if your security precautions were clearly not up to scratch?

Remembering that Joseph Popp’s scam foundered at least in part because actually paying the blackmail money to Panama was simply too hard, experts have suggested numerous civil sanctions aimed at making “pay up” into an unattractive or unavailable option for ransomware victims.

The theory is to impel companies to invest in proactive anti-cybercrime techniques, instead of taking a gamble by paying hush money after an attack to keep things quiet.

Various levels of regulatory control have been proposed, including:

Australia has become the first country in the world to put the third option above into effect for all types of business.

Companies don’t face an outright ban on paying cyberblackmail money, but they are required to disclose any ransomware payoff of any sort.

(Companies with a turnover below AU$3,000,000 a year [about US$2M, GB£1.5M] aren’t yet covered by this law.)

Notably, although the law uses the words “Ransomware reporting obligations,” companies can’t easily sidestep the regulations by arguing that no malware was involved, or that no data was scrambled, or that the blackmail didn’t fall unto the category of a “ransom” because nothing was returned or handed over as part of the payment.

The Australian government has made it clear that it is interpreting the word ransomware in its general and recent meaning, rather than in the limited and specific file-scrambling sense that it had when it was coined back in late 1989.

There doesn’t need to be any explicit -ware (in the sense of software installed and used for harm), or any strict ransom- (in the sense of a payment for some active, positive outcome such as the return of deleted data or the provision of a working decryption key).

Paying for any sort of passive, negative outcome is covered too, such as when attackers demand money not to leak stolen data, or not to attack the network again, or not to sell access codes on to other criminals.

And handing over negotiations and the payment of the blackmail to a third party so you can claim not to have paid up yourself doesn’t get you off the hook, either.

Nor does burying the payment as some sort of benefit-in-kind, such as admission to a bug bounty program or the provision of free products and services:

[This regulation imposes] reporting obligations on [most companies that] are impacted by a cyber security incident, and who have provided or are aware that another entity has provided, a payment or benefit (called a ransomware payment) to an entity that is seeking to benefit from the impact or the cyber security incident.

So far, the Act doesn’t require companies to admit publicly that they paid up, and indeed imposes fairly tight restrictions on what the Australian authorities can do with the reports they receive.

For example, the evidence submitted in a ransomware report can’t be published by the government, and can’t be used directly in any criminal prosecution against the company that provided the report.

But that doesn’t create a sneaky way for malevolent companies to cover themselves against criminal charges by “outing” evidence in a ransomware report and thereby “burying” it under some sort of legal privilege in future.

The Act explicitly notes that this caveat “does not apply to information held by [a Federal] or State body to the extent that it has been otherwise obtained.”

Presumably, if criminal charges were warranted, relevant evidence could be acquired directly under existing investigative rules and regulations, and introduced on that basis, even if that information had already been revealed in a ransomware payoff report.

Expect other jurisdictions to follow suit.

Many countries already have implicit rules about ransomware disclosures, because many ransomware attacks involve data breaches that need disclosing anyway.

Some countries already have an outright ban on some ransomware payments, for example by formally sanctioning payments to specific threat actors and threat groups, even though those actors may be protected from arrest in their home country.

Remember that cybersecurity prevention is always better than cure, not least because stolen data can never be considered safe from disclosure.

After all, if your data was stolen by criminals for very purpose of blackmailing you into paying hush money, what possible reason could you have to trust those same extortionists to be “honest” for ever after?

Learn more about our mobile security solution that goes beyond traditional MDM (mobile device management) software, and offers active on-device protection that’s more like the EDR (endpoint detection and response) tools you are used to on laptops, desktops and servers:

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.