We’ve written (and spoken) about the fecklessness and unreliability of ransomware criminals before.

It’s obviously unwise actually to trust ransomware attackers, given that by the time their extortion demands arrive, they’ve already provided unbeatable proof of their untrustworthiness.

Typically, by the time you have been squeezed into “negotiating” with them (to use the legal-sounding and upbeat terminology they like to apply to their own “work”), they’ll already have committed one, some, or all of the following crimes:

But ransomware criminals have regularly shown themselves to be dangerously incompetent, even when their apparent intention was to do what they said, namely to delete all stolen files and to provide a reliable method to recover scrambled files to get your business back on track.

If the media player above doesn’t work, try clicking here to listen in a new tab.

Well, here’s some further evidence that even criminals who apparently go out of their way to attack high financial value targets․․․

․․․write checks, if you will accept that metaphor here, that their abilities can’t cash.

This example involves the notorious Nitrogen ransomware, apparently derived from the source code of earlier malware known as Conti and Conti 2, which was “leaked” by disaffected ransomware gang affiliates some years ago, and published where the whole world could find it.

Nitrogen takes aim not at a company’s laptops and desktop computers, but at its ESXi servers, typically used by large businesses to host virtual machines for critical computing services such as websites, collaboration tools, payment systems and more.

Recent reports from cybersecurity companies investigating attacks using the Nitrogen code revealed a ruinous buffer overflow in the Nitrogen malware.

Loosely speaking, it’s as though the criminals used unbreakable padlocks to lock you out of every filing cabinet and storage closet in your business, put all the padlock keys into a bucket that they offered to sell back to you, but didn’t notice that the bucket had a hole it it.

Although they still had the bucket, the keys had all fallen through the hole.

Even if you were willing to meet their blackmail demands, there was nothing worth paying for.

According to code dumps published online, there’s an out-of-bounds memory write, where a program blindly stores data in the wrong place, and a buffer overflow, where a program intends to save data in the right place, but writes out more bytes than it should and tramples on adjacent data values.

The Nitrogen ransomware code saves a 32-byte data blob known as a public key for each encrypted file, with which the actual decryption key needed to unscramble that file can later be recovered, assuming the victim pays up.

(Technically, the victim pays for a private key, held hostage by the criminals, which can be combined with these public keys to recover the scrambling keys needed to decrypt each file.)

But the malware then saves a 4-byte representation of the number zero (0x00000000) in the wrong place, straight over the start of the public key.

There are 232 (about 4 billion) different values that a four-byte number can store, so there’s only a 1 in 232 chance that the public key started with four zeros before the bug triggered.

That makes a (232−1)/(232) ≈ 99.99999998% chance that the key just got ruined.

Then, to add insult to injury, the program also then writes the value 32 (perhaps the programmer wanted to save a count of the number of bytes in the public key?) to a four-byte memory area allocated just before the public key.

Except that the programmer saved the number as an 8-byte variable instead, overwriting the first four bytes of the public key all over again.

This sort of mistake is easy to make when you’re trying to share code and data between Windows and Linux (or ESXi), because the 64-bit Windows and Unix-like worlds handle numbers differently. In C, you’re guaranteed that a numeric vairable declared as a long int is at least 32 bits (4 bytes) in size, but it is allowed to be bigger. On Windows, a long int is indeed exactly 32 bits long, but on most Unix-like systems, the same variable will take up 64 bits (8 bytes) instead.

Most reports so far have insisted, in a loosely accurate sort of way, that because the public key gets damaged by this bug, and because the private key needed to regenerate the public key has already been deleted, then decryption is impossible, even with the full co-operation of the attackers.

As a result, even a victim who is willing to pay up would be wasting their money.

That’s good advice, but it’s not entirely correct, and the details reminds us that making absolute claims about cryptographic strengths and weaknesses, such as “decryption is impossible after XYZ has happened,” can be a risky business.

Does damaging part of a public key for which the related private key no longer exists really “destroy” the key forever?

For example, if your interest was to not to get the data back but instead to be certain that no one else could ever do so (for example to prevent the extraction of leftover data from decomissioned devices), could you be confident that just 32 bits of cryptographic corruption would be safe enough?

The answer, at least for this ransomware, is actually, “No.”

The Nitrogen malware uses the Curve25519 algorithm, standardized under the name X25519, where X is short for “key exchange,” and 25519 comes from the fact that this algorithm makes use of the prime number 2255−19.

An X25519 private key, loosely speaking, is a randomly chosen 256-bit (32-byte) number, and the corresponding public key is calculated from it using a mathematical formula known as elliptic point addition, also called scalar multiplication.

We won’t go into the details of that process here – that’s a story for another time – but the neat thing about X25519 is that although you can quickly compute the public key that goes with any private key, you can’t run the calculation in reverse, so you can’t recover the private key from the public key.

Next, let’s create two public-private keypairs, which we’ll call (Xprv,Xpub) and (Yprv,Ypub).

Now we can use the elliptic point scalar multiplication algorithm to combine Xprv and Ypub (your private key and my public key), like this:

And we can also combine Yprv and Xpub, which is my private key and your public key:

Note that we get the same answer both ways.

In other words, we can openly exchange our public keys, so-called because they are safe to reveal – they can’t be wrangled backwards to recover the private keys.

After that, we can separately, but safely and securely, derive what’s called a shared secret, which we can use for mutually secure encryption.

Even if a spy or a criminal intercepts both public keys during the exchange (for example, when setting up a browser-based e-commerce transaction), they still don’t get enough information to figure out the shared secret.

The nasty trick that ransomware crooks use is that after generating “your” public-private keypair and mixing “your” private key with their public key (which they can simply build into the malware if they wish, because it’s not meant to be kept secret), they deliberately throw away “your” private key.

From this point on, the only way you can recover the necessary shared secret is to combine your public key with their private key, which they have kept to themselves.

It’s their private key that they offer to “sell” you if you cough up the blackmail money.

Of course, given that you no longer have “your” private key, you’d better not lose the corresponding public key.

One full keypair or other won’t do the trick – because the whole idea is to exchange public keys and mix together half of each keypair to create the shared secret.

Simply put, at the blackmail stage of a ransomware attack, if either the criminals lose their private key, or you lose your public key, you’re sunk.

For mathematical reasons, X25519 public keys aren’t truly 32-byte random numbers, because not every possible 256-bit value is a valid public key.

But if we pretend that they are, then we can (in theory, at least) try replacing the four corrupted bytes of each Nitrogen public key by every possible 4-byte number in turn: 0; 1; 2; and so on, all the way up to 4,294,967,295 (which is 232-1, the largest number you can represent directly in 4 bytes, or 32 bits).

One of these trial values will produce the right shared secret; that shared secret will produce the right file unscrambling key; and you can detect when you probably have the right key because it will produce sensible-looking output, assuming that we can predict what the first few bytes of each decrypted file should look like.

And, in real life, we probably will know what to look out for: VMWare disk images start VMDK; Microsoft Hyper-V images start vhdxfile; ZIP archives (which include Office files) start PK; and many other files start with so-called magic numbers of this sort.

In other words, although we can’t regenerate the private key that would make recovering the public key trivial, we can run a brute force attack, using the 28 bytes of the damaged public key that we still have.

This should make it possible, in theory at least, to decrypt some, many or all of the scrambled files, assuming we’ve already paid off the crooks for their private key.

Having got this far, however, trying more than 4 billion public keys as a precursor to decrypting each and every file sounds like a very tall order.

Is it possible? Feasible? Practicable?

Yes, it is.

The X25519 algorithm, introduced in the mid-2000s, was carefully designed to provide similar levels of security to other popular public-key encryption systems of its era, while using less memory and being efficient even on low-powered devices such as mobile phones or IoT products.

Shared secret derivation can be done very quickly, typically at a rate of several tens of thousands of public keys per second on single CPU core on a commodity laptop.

On my own laptop, for instance, after just a few minutes of programming with a pure-C open-source implementation of Curve25519, I could easily exceed 40,000 trial keys per second using a single process.

With 16 cores running in parallel, the total rate reaches about 500,000 keys per second.

Trying 232 possible public keys would therefore take slightly more than 8000 seconds, or about two-and-a-half hours.

Indeed, if you had an ESXi server that was offline already due to being hit by this ransomware, you could use the raw server to help you with its own repair.

Booted into a memory-only Linux distro of your choice, you could reasonably expect a key recovery rate 10 times quicker than that, taking about 15 minutes per key using just one server.

Each scrambled file has its own decryption key, shielded by its own damaged public key, so you’d need 15 minutes per file you wanted to recover.

So you could almost certainly rely on finding about 100 keys a day (there are 96 quarter-hours in one day), which might well be enough to get your most important virtual servers running again, and your business back in its feet.

Make no mistake – this article is not meant to encourage anyone to pay a ransomware demand, whether the malware involved is Nitrogen or any other.

It’s intended to re-iterate two points:

Ransomware attackers often write checks their technical abilities can’t cash, even if you ignore their inherent criminality and dishonesty.

And cryptography “experts” often make security claims that don’t stand up, even if their intention was to be honest, because cryptographic correctness is hard.

Notably, numbers like 232 used to sound impressively large when applied to cryptographic cracking tasks, back when the DES encryption algorithm still used 56-bit keys, and internet download speeds were measured in kilobits per second.

Not any more!

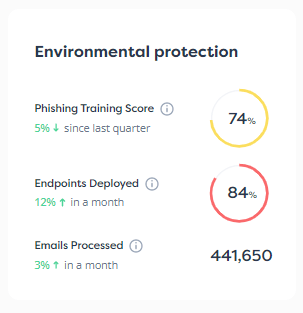

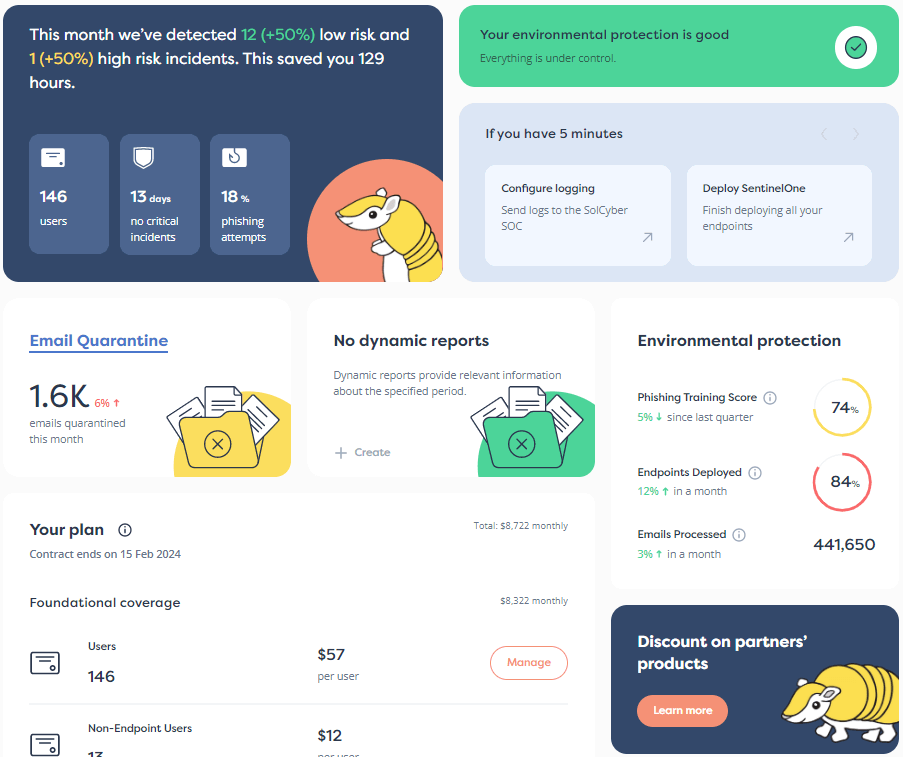

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of nitrogen dioxide gas at various temperatures by Efram Goldberg via Wikimedia, under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.