Annoyingly, or perhaps a better word would be dangerously, many bad cybersecurity habits of the past live on for years after we know we should have got rid of them.

A fascinating example is the use of the remote-access protocol officially known as TELNET and codified in RFC 854 more than 40 years ago.

Intriguingly, TELNET isn’t an acronym and it isn’t an abbreviation, though TEL- obviously denotes “far away,” as in telescope, and -NET refers to “networking.”

The name therefore conjures up a 20th-century image of a teletype (an old form of remote terminal that communicated over dedicated wired connections) running over the internet instead of over the phone company’s network:

The purpose of the TELNET Protocol is to provide a fairly general, bi-directional, eight-bit byte oriented communications facility. Its primary goal is to allow a standard method of interfacing terminal devices and terminal-oriented processes to each other. It is envisioned that the protocol may also be used for terminal-terminal communication (“linking”) and process-process communication (distributed computation).

It’s more often written in small letters these days, because the client and server programs that usually implement it are known as telnet and telnetd respectively.

In this article, however, I’ll write TELNET for the protocol itself, and telnet for software using that protocol.

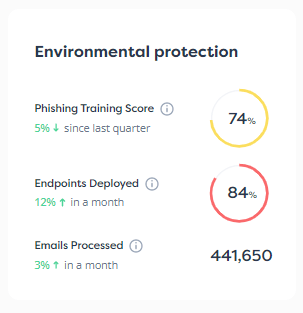

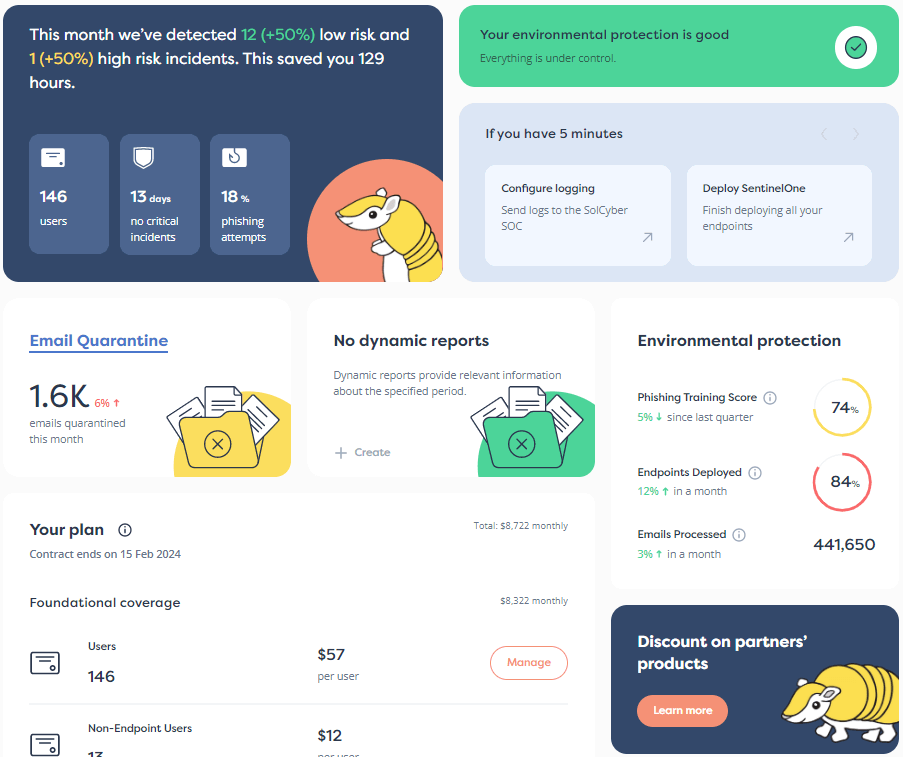

If you’re a LinkedIn user and you’re not yet following @SolCyber, do so now to keep up with the delightfully useful Amos The Armadillo’s Almanac series.

Even if you know all the jargon yourself, Amos will help you explain it to colleagues, friends, and family in an unpretentious, unintimidating way.

As you probably know, TELNET has always been risky to use, and becomes riskier still as the client and server ends get further apart on the network, because everything sent from one end to the other is transmitted “in clear,” a cryptographic jargon term meaning entirely unencrypted.

Of course, most internet protocols were unencrypted back in the 1980s and early 1990s, including SMTP (email), HTTP (web traffic), FTP (file transfer), and more, meaning that all sorts of private data could be snooped on and even modified undetectably along the way.

The insecure nature of TELNET therefore didn’t raise many red flags at the time, though we’ll see just how dangerous cleartext logins really are at the end of this article.

In 1995, a security-conscious computer scientist in Finland named Tatu Ylönen came up with a cryptographic protocol and software to support it called SSH, short for secure shell, where the word “shell” is Unix shorthand for a terminal window or a command prompt.

His SSH software formed the basis of the security-conscious OpenSSH toolkit, currently the most widely-used SSH implementation around.

Many network routers rely on it, and almost every Linux and BSD distro provides it as a standard package, as do Windows and macOS.

OpenSSH includes numerous other important SSH-based tools as well, notably SCP and SFTP, or secure copy and secure file transfer protocol, which use the SSH protocol for securely exchanging files.

If you use GitHub for source projects, or a cloud-based service for blogging, you probably use these tools in some form when you’re uploading new content or downloading backups.

Happily, SSH is about as easy to use as TELNET (the client-side software takes care of most of the tricky cryptographic stuff for most users), so it quickly started to supersede TELNET, and become one of the first cryptographic adoption success stories of the internet era.

But TELNET didn’t die out altogether.

Firstly, existing remote access tools still work fine over the TELNET protocol, whereas switching to SSH usually means adapting the software and scripts used at both ends of the link, which could mean getting someone else to make the switch in tandem with you.

Secondly, the insecurity of TELNET isn’t obvious until you stop and deliberately take a look at network traffic that uses it. (Read to the end of the article for a revealing packet capture.)

Thirdly, lots of routine traffic still goes unencrypted over local networks, notably wired local networks, which are often considered “safe enough” because they’re physically limited to a single office, or to a private server room.

However, because TELNET is a left-over artifact from days gone by, there’s not much interest in developing or maintaining the remaining implementations of the protocol.

Those sysadmins that still use it (perhaps by compulsion rather than by choice) have little option but to rely on the same old code they’ve been using for years.

One such toolkit is the GNU InetUtils package, which was last updated in January 2026, mostly to fix some embarrassingly ancient typos in the software comments, but also to fix a stack-based buffer overflow, albeit one that probably wasn’t exploitable.

This may give the impression that that the code is still receiving cybersecurity-related attention, but it seems certain that no one is being paid or sponsored even in the most modest way to do that job.

Sadly, shortly after the update to version 2.7, dated 2026-01-14, came a bug disclosure warning on oss-sec, the well-known Open Source Security mailing list:

If you are tired of modern age vulnerabilities, and remember the good old times on bugtraq [a full-disclosure list that shut down entirely in 2020], I hope you will appreciate this one. If someone can [allocate] a CVE, we will add it in future release notes.

/Simon [Josefsson]

# GNU InetUtils Security Advisory: remote authentication by-pass in telnetd

For reference, the CVE identifier now allocated is CVE-2026-24061.

Here’s how the bug plays out in real life.

(I’m not going to disguise the details, because exploiting it is trivial, and instructions and scripts on how to do it have already been promoted widely.)

The telnetd server-side daemon program doesn’t handle network connections directly.

Like all the server tools in the GNU InetUtils suite, a top-level server program called inetd, known jocularly as a super-server, listens for connections on multiple TCP ports, and fires up a new telnetd process every time a TELNET request comes in, usually on port 23.

Loosely speaking, inetd handles incoming connections and launches telnetd, which then negotiates connection options with the client, such as how to close the connection, whether to use extended character sets, and so on.

The telnetd program turns control over to the standard Unix login program, typically /bin/login, which handles any needed authentication, such as asking your username and password, and then runs a command shell program where you can launch scripts and programs of your choice.

In my tests, I used a tiny and much simpler server-side utility called onenetd, which is a minimalist replacement for inetd that deals with just one port at a time. It runs in the foreground, so you can’t leave it running by mistake, and needs no configuration files. It’s available in source and binary form from my GitHub page.

I tweaked the GNU telnetd code to send back a sequence of DEBUG lines to report that it was about to run the all-important login program, as a simple way to monitor its run-time behavior.

I then used the telnet client program to connect from a computer called red.test to the TELNET server blue.test.

The debug strings are colored blue by the remote telnetd program as a reminder that they come from the server:

As you can see, the remote telnetd daemon ran the /bin/login program, which is where the login: prompt came from, with a series of command-line arguments.

We don’t need to worry too much about those arguments, but -p means to protect important session variables in what’s known as the environment from being fiddled with, and -h red.test means to record activity about this session in the system log with the tag red.test, the apparent name of the computer that just connected.

Loosely speaking, the login program generally needs to run under the all-powerful root account (indeed, the -h option that telnetd uses requires it to do so, because that option affects the system log).

As a consequence, both telnetd and login are usually set to run as root, at least until you’ve logged in, after which the session will settle back to the privilege of the username under which you authenticated.

Often, when you TELNET to a remote computer, you’ll want to login there with the same username as you have on the client side.

You can do this by adding the command-line option -a for “attempt automatic login,” which passes your current username over the network to telnetd, asking it to append the name to the command-line options it hands onwards to the /bin/login program.

This handily skips over the the login: question, straight to the Password: prompt:

So far, so good.

As it happens, you can override the choice of automatic username by setting a special environment variable USER when you run the telnet command:

In theory, this doesn’t reduce security, because the default behavior of telnet is to prompt you to login under any username you like, as we saw above.

But just how much care do you think the telnetd program at the other end takes with that special USER setting we sent over to it?

If we sneak a space character in there, what will happen?

Will the other end include the space character in the username it asks for?

Will it conservatively reject the username as suspicious?

Or will it helpfully but recklessly split the username into two separate command-line options and use them both?

We can find out pretty quickly by trying a USER value that consists of a valid username, followed by a well-known command-line option:

Oh, dear!

We can pass across not only any username we like, but also inject extra command options of our choosing that the /bin/login program at the other end will obey.

And, as you can see from the --help information that the /bin/login command helpfully and trustingly sent back to us, the option -f seems very worrying indeed.

It looks as though -f was chosen as shorthand to denote “fly straight past the login authentication part,” and that is exactly what happens if we use it:

Note how the sneaky USER setting we chose parachuted us directly into the account of showme on the server blue.test, with no Password: prompt at all!

Guess what’s coming next?

Why break in as showme if we can reach greater heights with the same trick?

Straight in as root, with no password.

As you can see above, the id command confirms that I have the all-powerful superuser UID (user id) of zero.

While I was in, I was able to do some rogue sysadministration too, quickly creating a new account called backdoor, assigning it a password, and getting straight back out again.

Even if the sysadmin of blue.test turns off TELNET altogether after reading this article, or applies some sort of mitigation for this security hole, I’ve still got a way back in, this time via SSH, using a regular account with a regular password:

For what it’s worth, this passwordless login trick can also be triggered by using the -l option of the telnet program, which takes your desired login name directly from the command line instead of from the USER variable:

Surprisingly, perhaps, given the ease with which this bug can be exploited, no patch is available, even though it’s already a week at the time of writing since the disclosure first came out and hit the news.

However, patch or no patch, no one should be using TELNET these days, whether that’s the GNU InetUtils implementation or any other.

Sadly, you’ll still find TELNET access available, sometimes even by default, in embedded and internet of things (IoT) devices, and news reports suggest that this vulnerability has provoked renewed interest from ne’er-do-wells who are actively scanning the internet for any TELNET services still out there to exploit.

The solution, therefore, is not to seek a patch for this old-time code project․․․

․․․but to use it an a dramatic prod to do the right thing and banish TELNET from your digital life, especially if you’re a device vendor who is still inflicting it on other people by running it as a service.

Here’s why.

This Wireshark network capture shows what happened when I accessed the showme account on blue.test:

Worried about getting stuck with the challenge of finding buggy apps for yourself, then figuring out the risk to your business, and then doing something about it?

Stuck with an existing approach that is full of technology and tools, but light on humanity and lacking that human-centered approach?

Don’t get lumbered with an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers.

Talk to SolCyber today!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.