The widely-used GPG software recently patched a critical vulnerability that tells an interesting and educational story about cybersecurity in general – what you might call lifestyle security, rather than merely security-by-compliance.

If you’ve been around computers for a while, you’ll probably remember a program called PGP, which caused all manner of controversy in the early 1990s.

PGP stands for Pretty Good Privacy, written and published in the US by a security and cryptography enthusiast called Phil Zimmermann in 1991.

Zimmermann made the product free for non-commercial use, and published its source code so that experts could inspect it, critique it, and check it out to ensure it didn’t have any cryptographic booby-traps or backdoors in it.

This was a reasonable thing to do, because some vendors of proprietary encryption systems have been caught out over the years sneaking hidden backdoors into their products, for undisclosed uses by undisclosed third-parties.

At the time, however, the US classified encryption tools as munitions, just like guns and bombs, and you needed a license to export them from the country.

So, even though Zimmermann didn’t sell his software outside the US, there were already sufficiently many people worldwide on the early internet that the source code was widely downloaded from outside the US and turned into working software by inquisitive users living overseas.

Unofficially speaking, it was as though those users had “exported” the PGP program, albeit in a new and unusual way.

Zimmermann therefore became a person of interest to the US authorities for allegedly violating export laws, but wisdom eventually prevailed, the investigation was dropped in 1996, and he never faced court.

By that time, proprietary or undisclosed encryption algorithms were widely considered a bad idea, and Zimmermann’s open-source approach was seen as a huge advantage, to the US as well as to the global internet.

The desirability of openness in cryptography came about not only because of the serious breaches of trust mentioned above, but also because the world had realized that even the smartest and most trustworthy programmers were likely to end up with insecure algorithms if they were left to design their code in a intellectual vacuum.

As an old cryptographic saying goes, “Anyone can invent an encryption system that they can’t crack themselves,” but encryption algorithms need to be unbreakable by everyone, not just by their creators, however careful and well-intentioned they may have been.

So, with the potential legal jeopardy of PGP laid to rest in the US, numerous variants began to appear, along with an evolving public standard known first as PGP Message Exchange, and later as OpenPGP (now RFC 9580 in its most recent incarnation).

One of the best-known PGP-derived software programs these days is GNU Privacy Guard, or GPG (see what they did there?), a free and open-source implementation that is included as a standard package in numerous Linux distros.

For better or for worse, GPG has grown into a complex, interconnected set of libraries and tools, including programs called gpg, gpg-agent, pinentry and dirmngr.

GPG also defines various mechanisms for shuffling data between these components, including the curiously-named Assuan, a text-based protocol for various purposes, including requesting passwords from users via pop-ups and the like.

I can’t find a definitive explanation for the origin of the protocol name Assuan in GPG. I’m guessing it is a Victorian-era spelling of Aswan, as in the Aswan region of Egypt, where the Aswan High Dam across the River Nile now stands. This region is associated with tombs, temples, carvings, inscriptions and esoteric messages dating back more then 5000 years. It was once known as Syene [Συήνη, usually said as siEEnee in English], under which name it is associated with Eratosthenes of Kyrene (he wasn’t from Syene himself). Syene is very close to the tropic, where the sun is directly overhead once a year, a fact that Eratosthenes used in estimating the circumference of the earth, way back in about 250BC. The name is therefore associated both with esoteric writing systems and with scientific endeavor.

Even if you’ve never knowingly used GPG, or perhaps never heard of it at all, your password entry and cryptographic security may nevertheless depend on it if any of the software or services you use, locally or in the cloud, make use of its various components.

GPG and its protocols are reasonably widely deployed for acquiring and and processing cryptographic keys, and for encrypting and decrypting secret data, notably in email.

Indeed, the GPG team recently fixed a critical bug relating to the product’s use for what’s known as S/MIME, short for secure multipurpose internet mail extensions, often used by email services that offer true end-to-end encryption.

Most server-to-server email transfer these days uses TLS (transport layer security) to protect your messages during delivery, but that isn’t true end-to-end encryption.

That’s because the servers themselves (for example, Microsoft’s webmail service at one end and Google’s at the other) add and remove this TLS encryption on top of, and separately from, any encryption you may have applied yourself.

Likewise, if you use a web browser to send and receive email, the connection between your browser and the email service is encrypted and protected with TLS, but that encryption is added and removed just to secure the data in transit.

(That’s much better than nothing, because it stops just anyone snooping on your data as it goes across the internet, but once again it’s not your encryption, and if you send an unencrypted email, the mail service you’re using will see the raw, unscrambled data once the TLS is stripped off.)

S/MIME, in contrast, aims to encrypt and to protect the integrity of your email data before and after it’s transmitted to and from your email provider.

That way, it remains encrypted by you even while it’s being processed, stored temporarily along the way, and then passed on.

Any TLS encryption added when you use webmail, or when your mail provider passes messages from server to server, is therefore just another layer of protection on top of your own end-to-end security.

Loosely speaking, when someone wants to send you encrypted messages or attachments, they choose a random encryption key for each message, for example a key for the AES cipher.

They then encrypt that secret, or symmetric, key with your public key, and then package all of the needed public cryptographic material, along with the encrypted secret-key-and-data, into the message.

This apparently long-winded approach, combining two sorts of cryptographic system, is used because public-key encryption isn’t good on its own for long messages.

Instead, cryptographers take a hybrid approach.

They use a fast, symmetric, secret-key cipher like AES to shield the message, which may be megabytes or longer, and a public-key algorithm such as elliptic curve cryptography to shield the one-time AES message key, which is typically only a few tens of bytes in size.

As long as you keep your private key private, only you (or your S/MIME software on your behalf) can unravel each per-message key, so only you can unravel the full original message, so only you can read it.

Some data about the message, known in the jargon as its metadata, such as the time it was sent, who sent it, how big it was, and so on, will still be open to outside scrutiny․․․

․․․but neither your ISP, nor your mail provider, nor anyone else along the way, nor the recipient’s mail server, nor the recipient’s ISP, will be able to extract the end-to-end encrypted attachments in the message.

And therein lies the bug that was fixed.

The sender gets to choose the per-message secret key, and to package it into the email they send.

That per-message key, assuming they used the AES algorithm, will always be either 16 bytes (128 bits, the keysize for AES-128), 24 bytes (AES-192), or 32 bytes (AES-256) long – those are the only three key sizes that AES supports.

These sender-generated keys are packed up into a digital container using an algorithm known as a KEM, short for key encapsulation mechanism.

KEMs aim to provide safe and well-defined ways of packaging cryptographic keys, rather than letting every program come up with its own way of exchanging key material and thereby ending up with an unstandardized digital mess.

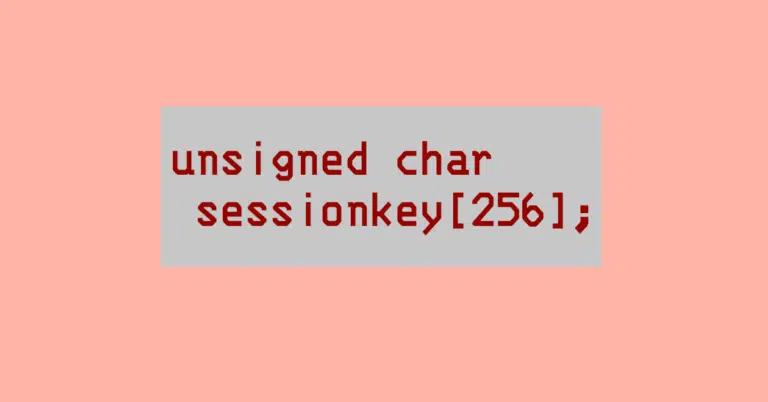

Given our mention that AES keys are at most just 32 bytes long, you can guess where this is going.

The GPG programmers who wrote the code to unpack AES keys would have known that any decapsulated key (that’s the jargon shorthand for extracting a key that has been packaged by a KEM) would fit into 32 bytes of memory.

So they apparently figured that reserving a chunk of memory “with plenty of spare room just in case” would be fine, and therefore allocated a fixed-size buffer of 256 bytes, instead of working out how much was really needed each time and reserving the right amount.

Their next coding shortcut was that they didn’t make sure that the sender of the message really did send a proper key, rather than, say, one 400 bytes long that [A] could not possibly be valid, and [B] much more importantly, would not fit into the otherwise-generous 256-byte buffer they’d set aside.

So, if an incoming key was more than 256 bytes long, whether by programming accident or by cybercriminal design, the code never got as far as checking that the key was invalid.

The decapsulation process itself burst the bounds of that 256-byte memory buffer first. (This bug is now assigned the identifier CVE-2026-24881.)

As the bug report puts it, “The overflow occurs before [any] integrity checks complete.”

The report also points out that a deliberately-malformed encryption key will always cause a “denial of service via a gpg-agent [program] crash,” given that the bogus data corrupts the running program directly.

What’s worse, though, is that the report notes that because of the precise control that an attacker has over the data that overflows the buffer (given that the sender gets to decide exactly how many bytes to send over and above the 256 that will fit), this “memory corruption represents a plausible code-execution primitive depending on platform and hardening.”

That’s a compressed, jargon-heavy way of saying:

With some care and a bit of luck, the attacker may be able not only to crash the receiving program for sure, but also to do so in a way that lets them control what happens next at the other end, up to and including injecting malware onto the recipient’s computer, even if all the recipient does is try to view an encrypted message.”

In a word, or more precisely in three words: RCE, short for remote code execution, generally the most worrying sort of security bug.

If you’re a programmer, there are two vital things you always need to do before and while you unpack data to check whether it’s valid:

If you’re a sysadmin:

As an intriguing and ironic aside, it seems that this bug was introduced when GPG’s key decapsulation code was changed just over a year ago․․․

․․․and that those changes were made to ensure that its KEM, or key encapsulation mechanism, complied with the latest US Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS).

Just to be clear: Compliance alone is not correctness!

Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.