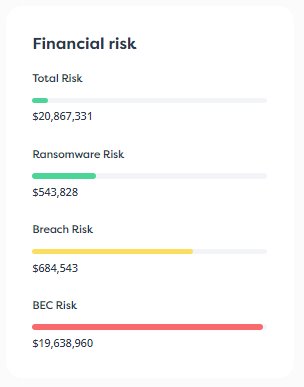

You’ll hear an array of different shorthand jargon terms including ‘BEC’, ‘CFO fraud’ and ‘spearphishing’ used to refer to cyberscams that trick you into paying invoices, perhaps even substantial ones, to the wrong person.

We take a look at how the crooks go about scamming both purchasers and suppliers, and what you can do to protect yourself and your business.

Few of us get paid in cash anymore, with the flipside that few of us pay for things in cash, either.

Ironically, when we did pay in cash much more than we do today, one of the overriding concerns we had (if you ignore the risk of being robbed of the money on the way to pay, of course) was making sure that we handed over the money to the right person, in the right place, at the right time.

Companies that paid wages in cash would require staff to show up in person, identify themselves, sign their payslip, and have their pay packet thrust directly into their hands.

Likewise, as purchasers, we wouldn’t just hand a wedge of banknotes to a random person in a shop when we went to acquire a new washing machine or TV, and the store we were buying it from would go out of its way to prevent ‘deals’ like that happening anyway, in case there was some unscrupulous collusion going on.

No matter how much times have changed, however, we still need to take great care of when, where and to whom we make online payments, for many reasons, not least that cybercriminals are out to get us if we don’t.

Those reasons are what we’re going to look at now, as we explain a range of cybersecurity buzzwords that can be quite confusing, given that they describe a range of different, yet similar and overlapping, types of cyberfraud.

The three buzzphrases we’re looking at today are: BEC, CFO Fraud, and spearphishing.

In truth, they’re not very good terms at all, because they’re annoyingly ambiguous, and because they’ve variously become attached to criminal activities that they don’t describe very well, which can cause confusion.

We’ve taken a look at BEC before, and already published some really useful advice on avoiding it, right here on this blog, but today we’re going to dig a bit deeper into the history of the term, based on the most dangerous form of account payment cybercrime.

The acronym BEC, pronounced beck as if it were the north-of-England word for a small stream or brook, is often treated these days as though it were a word so widely understood that it doesn’t need expanding any more, like TV, RAM or FBI.

BEC stands for business email compromise, and refers to a very particular form of email-based cyberattack where the rogue emails you receive from the scammers aren’t just buffed up (or spoofed, in the jargon) to look as though they came from an email account inside your company…

…but actually, did come from a real company account, just not from the account’s real user.

The hint is in the name: the words ‘business email compromise’ are meant to warn you that the crooks have already broken into your email system, and are therefore already inside the house, so that their messages have a technical and visual legitimacy that spoofed emails from the outside can never quite achieve.

Most BEC criminals take the same sort of long-game approach that we see from so-called romance scammers, who befriend their victims on dating sites and lure them into long-distance relationships that involve victims sending them regular sums of money over weeks or months (and, very sadly, sometimes for years), not merely once or twice.

Simply put, true BEC scammers don’t just ‘borrow’ your email passwords to send a couple of rogue messages, but instead dig themselves in deeply and quietly, as good as living in your inbox while they learn the ropes of how you do business, which companies you trade with, what account payment systems you use, and when various payments are due.

If they can, which is likely if they have login-level access to your account, BEC scammers will often set up a variety of different email filtering rules, possibly with official-looking or unexceptionable-sounding names, that capture and divert some or all of your incoming email into subfolders, so they don’t land directly in your inbox.

This means, of course, that the crooks get to read at least some of your emails before you do, selectively releasing the stuff they want you to see, and suppressing anything they don’t.

Like romance scammers, their criminal abilities (if you will allow that word in this context) aren’t usually technical at all – they may well have bought the account passwords they’re abusing on the dark web rather than hacking or cracking into your account themselves.

Their criminality revolves around persistence, commitment and frequency, so that they keep on top of your email as much as you do, aiming to ‘censor’ your incoming messages regularly and quickly enough that you don’t notice any tell-tale delays.

That way, even if someone else gets suspicious of messages coming from your account and replies to warn you, you never get to see the warnings at all.

Similarly, BEC scammers make sure they get rid of any messages from your ‘Sent folder’ that you didn’t send yourself, making it less likely you’ll spot their meddling even if you become suspicious and dig through your emails to look for anything out of place.

As you can imagine, by keeping track of the ins-and-outs of contracts, invoices and receipts that show up in the mailboxes they’re snooping on, BEC criminals can time their account payment scams perfectly.

The crooks probably know in advance all the relevant due dates and document numbers they’ll need, and they can easily duplicate your internal accountancy jargon simply by copying-and-pasting from earlier emails.

If the crooks aren’t sure, they can even ask around both inside and outside the company, precisely replicating your very own email signoff and tagline every time because your email system adds it for them automatically, and deleting both their questions and any answers they receive so you don’t catch them out.

The goal of most BEC criminals isn’t simply industrial espionage, though that is in fact what they are doing (and for all you know they may be selling any juicy confidential information they find as a sideline), but to convince other people involved in your accounts receivable and accounts payable activities that the details of one or more bank accounts in the payment process have changed.

It’s as direct as that, once the criminals have positioned themselves in the right hiding place.

Either they trick your company into paying some of its own debts to fake accounts instead of to the account of your real creditors, which obviously leaves both parties aggrieved and out-off-pocket…

…or they trick your debtors into paying invoices to fake accounts instead of to yours, again causing double-sided aggravation and loss.

Simply put, the crooks aren’t just hurting your bottom line and stealing from your business, they’re directly cheating and defrauding your business partners as well.

You’ll also hear this sort of criminality described by the nicknames CFO fraud and CEO fraud, although those words are perhaps more commonly being used these days in their literal sense to describe fraud that was conducted by a senior official in the company, such as the scamming for which Samuel Bankman-Fried, erstwhile CEO of notorious cryptocoin exchange FTX, was recently convicted.

Nevertheless, you’ll still come across those terms used ambiguously to denote crimes against the CEO and CFO, and you will encounter them in existing writeups of account payment scams.

After all, the company staff whose mailboxes provide the most leverage in attacks of this sort are, rather obviously, the CFO and CEO, and those are the mailboxes that serious BEC criminals will go after if they can.

Imagine an email that genuinely does come from the CEO’s mailbox, and that instructs you to make a large payment to what sounds like a legal firm as part of a merger or acquisition that the email says needs to be kept confidential for regulatory reasons.

Imagine that the message copies the CEO’s style well enough (CEOs often write notoriously brief and perfunctory messages, given that their job is usually to give instructions and expect them to be followed, rather than to follow instructions themselves).

Imagine that when you reply to make sure that the details are correct, you receive a short but precise confirmation that they are, reminding you not to discuss the ‘acquisition’ with, or to reveal ‘privileged information’ to, anyone else.

That’s why BEC criminals often put special emphasis on getting control over executive email accounts, because that’s where the information, influence and instructions about big account payments are concentrated, although they don’t need access to the CFO’s email to make this sort of attack work.

Fortunately, hacking email accounts isn’t quite as easy as it once was (Microsoft’s recent intrusion notwithstanding), so BEC-style crooks are often forced to rely on spoofed emails, doctored to appear internal but actually sent in from outside.

This has led to the term BEC being used in reports and articles to refer to any sort of rogue email that tries to divert payments to a fraudulent account, whether there really was an email compromise or not.

That’s a a pity, because true BEC incidents generally need a much more extensive and detailed threat response once you spot them than spoofing-based email attacks do, given that they implicitly also involve industrial espionage, as we mentioned above, and given that your threat responders need to check what else might have happened while the crooks were inside your network.

(The US Federal Trade Commission, America’s fair trading body, is now using the term Business Email Imposters to describe crooks who try to defraud you in this way, which I think is a better phrase to use if you want to keep the words business and email in your jargon.)

A higher-level, more general term you’ll hear for email tricks involving a deliberate effort to look personal, rather than using a generic ‘Dear Customer’ message, is spearphishing.

As the name suggests, with a purposeful touch of metaphorical drama, spearphishing refers to phishing attacks (messages that induce you to reveal or to do something online that you later wish you hadn’t) that are targeted at you and your business in a way that makes them seem personal, particular, and more believable that typical scam messages.

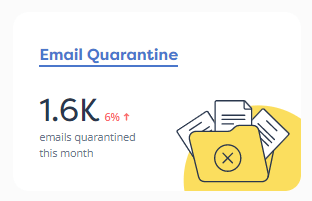

The language and grammar might be better than you’d expect; the spelling may be correct; the names and job titles properly researched; and the email details that show up in the fields From, To, Reply-To and so on will probably look realistic.

Like this simple yet effective example from the field recently reported by the SolCyber threat response team (DD, if you haven’t seen those letters before, means direct debit).

We’ve changed the names for anonymity (they all matched the names and job titles at the company concerned), but preserved the other details and wording:

Note that the message is surprisingly well-written, if not entirely correct (that’s all I’m saying – no hints for the crooks here!) and shows a neat trick that today’s cybercriminals are using, namely not trying to hit a hole-in-one.

The scammers didn’t say, “My new bank account number is X, please switch to it,” but instead invited a reply asking for further details, thus serving the scammers in two ways.

Firstly, even though this technically counts as personalised spearphishing, because the details in the message are carefully constructed, the crooks don’t have to follow up each message by hand.

They can use a script to send out thousands, even millions, of customised email probes in this vein, and rely on those who reply to single themselves out for follow-up.

Secondly, the crooks avoid revealing any actual bank account details in their initial burst of messages.

Bank accounts are comparatively difficult to set up these days, usually requiring on-the-ground accomplices to put themselves at risk of detection and arrest by fronting up to a real bank with fraudulent identity documents.

So, criminals in the account payment scamming underworld like to keep usable accounts quiet until the last possible moment, lest they get frozen proactively.

Remember that spearphishing attacks don’t require the crooks to know you personally, because emails of this sort can be made both personal and believable just with data fetched from sources that are already public, such as social media sites or data dumps from previous breaches.

Whether you call it BEC, CFO fraud or spearphishing, account payment fraud is important to look out for, not least because some deliberate payment diversions may go unnoticed for a month or more.

In fact, some frauds of this sort are spotted only after an account is flagged as delinquent by the creditor and handed over for debt recovery, thus adding insult to injury and making a bad thing even worse.

Remember two simple catch phrases: “If in doubt/Don’t give it out,” and “If you think it looks scammy/Back yourself and call it in.”

Here’s a longer example of a “CFO fraud” scam message intercepted by SolCyber researchers.

In this case, the message was sent directly to the target company’s CFO, addressing her correctly by name (we’ve anonymised her here as Angela Baker: angela@example.com).

The message claims to include an earlier email thread between the sender and the company’s CEO (Charles Delta: charles@example.com), and the sender claims to represent a legal services company.

Note how the fake lawyer’s message to Angela refers to an attachment that wasn’t included in the email, which not only avoids the need for the crooks to come up with a believable invoice in the first place, but also reduces the quantity of threat detection data available to cybersecurity software such as email filtering gateways.

Attachments are often omitted from emails that are replies or followups (many email clients ask you if you want to skip sending attachments back out in followup messages, especially on mobile devices), so the absence of the attachment is not particularly suspicious on its own.

The scammers are instead hoping that the recipient will reply to investigate further, no matter how quizzically or disbelievingly, and open up a communication channel through which the criminals can begin to develop the scam.

PS. If there are any knotty topics you’re keen to see us cover, from malware analysis and exploit explanation all the way to cryptographic correctness and secure coding, please let us know. DM us on social media, or

email the writing team directly at amos@solcyber.com.

More About Duck

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.