In some corners of cybersecurity, the saying “attacks only ever get better and faster” serves both as a warning and an encouragement, causing us to lift our game so that our defense gets better and stronger in response.

But the saying doesn’t seem to work that way when it comes to data breaches: despite more security tools, safer operating systems and stronger data protection regulations, data breaches often seem to be getting bigger and worse.

It doesn’t have to be that way, so what can we change to reduce the frequency and severity of data breaches, especially when we didn’t choose to have our data collected in the first place?

There’s a famous saying in cryptography, a word that literally means secret writing, namely that:

“Attacks only ever get better and faster.”

We presented a practical demonstration of this in a recent article about cryptographic cracking, where we investigated the security of the well-known RSA encryption algorithm.

RSA requires you to generate two large, secret prime numbers P and Q, used together as a private key for decryption; you multiply them together to make a number twice the length known as N, which you can publish openly as a public key for encryption.

This mysterious-sounding system works because personalized values of P and Q typically take just seconds to find, even when P and Q are each thousands of digits long, and calculating N = P×Q takes a tiny fraction of a second.

But working backwards to figure out P and Q from N alone is staggeringly difficult, because it can only be done by trial and error and the numbers involved are huge.

We went back almost 50 years to when Ron Rivest (the R in RSA, and thus one of its three co-inventors), offered the opinion that a public key N of 125 decimal digits would take more than 350 million million million hours to deconstruct (or factorize) back into its two prime factors P and Q, thus making the algorithm as good as uncrackable if used correctly.

We thought we’d see how that suggestion had held up, so we generated two random 63-digit prime numbers for P and Q, and multiplied them to make our own 125-digit value N:

Just to be clear: 350 million million million hours hours doesn’t just cover a human lifetime, or even the lifetime of humankind, but is an absurdly unimaginable 8 million times longer than the lifetime of Earth so far, and about the same amount longer than the remaining lifetime of the sun.

Yet in mid-2024, we unleashed a recent 16-core Linux laptop running a program called CADO-NFS that uses the best-known current prime factoring algorithm (the number field sieve), and asked it to split our supposedly safe-beyond-the-lifetime-of-the-solar-system number N back into P and Q.

How times have changed!

The cracking process took just under two hours:

Does that mean we might as well give up on encryption, given how much better and faster things have become for attackers?

Thankfully, it doesn’t, because we’ve continually been improving our cryptographic algorithms and standards at the same time, given that computers are more powerful for all of us, not just for attackers.

For example, we no longer use 125-digit values of N for RSA, but use numbers at least 600 digits long, and we now have a range of alternative algorithms to choose from that provide similar levels of security with less cumbersome key sizes, so we don’t have all our eggs in one basket.

Simply put, the scary-sounding truism that “attacks only ever get better and faster” doesn’t mean we’re bound to lose the cybersecurity arms race, because there’s a counter-truism that “defenses can be made stronger and harder to crack, too.”

Ideally, of course, that counter-truism really ought to apply to all aspects of cybersecurity, not just to encryption and decryption.

Sadly, the parts of cybersecurity that you might think are the easiest to fix, because they don’t involve esoteric mathematics, weird science and complex algorithms in the way that cryptography does, seem to the very areas where we’re struggling the most.

Take data breaches, for example.

We have cryptography that’s stronger and easier to use than ever, safer programming techniques, stronger protections built into our operating systems, faster updates, stricter data protection regulations, faster and more reliable backup services, better network management tools, and more and more cybersecurity vendors selling more and more tools that we’re told are game-changers.

But data breaches seem to be getting bigger and worse, as you’ve probably thought yourself recently thanks to the unfolding story of an organization trading under the intriguing name of National Public Data, or NPD for short.

NPD’s website proclaims that its services “are currently used by investigators, background check websites, data resellers, mobile apps, applications and more,” and invites you to “[j]oin now and enjoy quality data with low fees and no monthly minimums.”

The business justifies its name by explaining that it gives “access to the greatest level of public information retrieval available on the Internet,” describing itself as “a public records data provider specializing in background checks and fraud prevention [that obtains] information from various public record databases, court records, state and national databases and other repositories nationwide.”

Loosely put, it runs a web-based subscription service that provides an API (application programming interface) for paying customers to do their own searches against personal data supposedly scraped from locations where it has already appeared online.

The presumption seems to be that scraping the data makes the collected information fair game for commercialization.

After all, isn’t that what search engines such as Bing and Google do in a very general way?

Isn’t that what Google Street View does with company buildings, shops, private houses, apartment blocks, public parks, and more?

Isn’t that what the Wayback Machine at archive.org does with other people’s web pages, preseving them even after they’ve been edited, moved or taken down altogether by their copyright holders?

Isn’t that what thousands of so-called data brokerage companies already do with all sorts of data such as telephone numbers, electoral records, and internet domain registrations?

“Better and faster searching,” right?

Let’s get an idea of just how much “better and faster” things can get when we rely on public searches for details that would have been as good as private just a decade or two ago.

From NPD’s domain name nationalpublicdata.com, we can query its official registration details using the WHOIS protocol, but the true identities of the owner and administrators are shielded by a proxy company that provides the sort of privacy that wasn’t really allowed when internet domains first went on sale.

Even data brokerage services such as NPD that are happy to sell on your personal data insist on domain privacy for themselves, not least because the presence of genuine home addresses, phone numbers and email addresses in domain registration details turned out to be more useful to spammers, scammers and stalkers than to legitimate users:

Similarly, all we’ve got to go on from the NPD website is a toll-free phone number, a generic email address, and a contact mailing address:

Numbers at the end of a street address may sound as though they denote an office suite or an apartment number, but often they merely identify a postal drop at a mail service company, meaning that the actual location 1440 Coral Ridge Drive could be the registered address of tens, hundreds, or even thousands of businesses.

Google Street View can help us here:

We’re looking at a UPS Store, with a just-legible sign in the window advertising that the location is a “full service mail provider.”

A search for other companies at the same street address quickly brings up what seems to be a local dog-walking company, for which you imagine a real office would be superfluous, a long-defunct company that had the same “suite” number of #236, and an outfit called Jerico Pictures, a film-making business:

Assuming a business would choose a domain name to match its company name, it’s worth taking a look at the WHOIS data for jericopictures.com (note that it’s Jerico, not Jericho), which is immediately interesting:

And the company website is intriguingly uninteresting when we took a look:

But the top Google result for Salvatore Verini Jerico Pictures (if we ignore Google’s top-of-the-page advice that we probably meant to write Jericho) is truly fascinating:

This letter, direct from the US federal legislature, was mailed last week and explicitly references the data breach that has been all over the news since about the start of August 2024, when the civil lawsuit mentioned above was filed.

As you can see in the sequence of screenshots above, companies that scrape and index information that is at least in theory already publicly available can be really helpful when researching incidents such as cyber-breaches and corporate chains of responsibility.

We didn’t need to to travel to Coral Springs in Florida to see if our place of interest was a real office or just an accommodation address, or apply in writing to the Florida registrar of companies and then wait to receive ownership details via the postal service.

But the breach for which Salvatore Verini is now being held to account paints a very different and much more dangerous picture of the commercialization of so-called ‘public’ data.

Importantly, the NPD breach is a vital reminder of two worrisome cybersecurity risks confronting our personally identifiable information (PII) in today’s online world:

In the Hofmann lawsuit linked to above, the first of many federal cases now filed against Jerico Pictures [15 as at 2024-08-27T14:00:00Z], the complainants make this point, among many others:

[The plaintiffs] never provided their PII to [NPD].

However, despite this fact, [the complainants] still have the reasonable expectation and mutual understanding that [NPD], who used [their] PII for its own business purposes, would comply with its obligations to keep such information confidential and secure from unauthorized access.

We probably all sympathize with this statement, which boils down to the argument that it’s bad enough for you to collect my PII without asking me first, and it’s adding insult to injury to assume, because you didn’t ask and therefore I didn’t know you were doing it, that you therefore have no need to look after it properly.

(If you break into my house unlawfully to burgle it, and burn it down because you decide to make yourself a cup of coffee while you’re there but forget to turn off the stove when you leave with my TV, you can’t pretend you didn’t cause the fire because you weren’t supposed to be there in the first place.)

Unfortunately, perhaps, the scale of NPD’s carelessness has been widely and confusingly reported in the media, with reporters rushing to publish headlines suggesting “Nearly 3 Billion People Hacked in National Public Data Breach” and “Personal Data of 3 Billion People Stolen in Hack”

The Hofmann lawsuit probably kickstarted this sort of needless exaggeration, noting as it does that NPD “allows its customers to search billions of records with instant results” (which seems to be a fact), and following with the suggestion that “[the defendant] scrapes the PII of potentially billions of individuals,” (which is carefully worded as a theoretical possibility rather than as a fact).

But the presence of billions of records in a stolen database doesn’t mean there are billions of individuals who have each had one item of PII breached, any more than the 1.3 million entries in the long-term operating system log from my Linux laptop imply that I have collected system information about my own computer and 1,299,999 others.

(Those entries include regular repeated lines listing my system configuration at each reboot; they boil down to fewer than 120,000 data points if timestamps are ignored and duplicates removed; and in any case represent the data from exactly one computer with a single user.)

Even the letter from the Congressional Committee says, cautiously using the passive voice, that “it is reported that the personal information of nearly 3 billion people [was] compromised, with the stolen data including information such as Social Security numbers, phone numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses.”

Wiser minds have attempted to put the record straight, with investigative journalist Brian Krebs noting:

Many media outlets mistakenly reported that the National Public data breach affects 2.9 billion people (that figure actually refers to the number of rows in the leaked data sets). HaveIBeenPwned.com’s Troy Hunt analyzed the leaked data and found it is a somewhat disparate collection of consumer and business records, including the real names, addresses, phone numbers and SSNs of millions of Americans (both living and deceased), and 70 million rows from a database of U.S. criminal records.

Researchers at anti-identity theft company Constella also looked at the data; they suggest that it covers at most 294 million individuals, 272 million US social security numbers, and 32 million unique emails.

Fascinatingly, about 10% of the records scraped by NPD seem to cover people who were born between 1900 and 1930, very many of whom will now be dead, and only a handful of records exist for people born after 1990.

Constella also argues that only about 50% of the individuals in the list have lost what the company describes as the “minimal amount” of PII needed to make identity theft possible, implying that at least half of the breached data is useless for immediate identity-related crimes.

Admittedly, that doesn’t excuse the breach, and it’s cold comfort for the tens or hundreds of millions of people whose data was breached.

Also, stolen data that may be insufficient for identity theft or other financially-related crimes may nevertheless leave victims at the risk of stalkers (if their phone number or address in the database is correct), scammers, spammers and more.

Annoyingly, reports that overstate the size of any breach, especially if they overstate it by a factor of ten or more as happened here, don’t do us any favors, for all that the breach might be huge.

Drawing attention to real-world cybersecurity issues is important, but if a breach needs multiple millions of victims before it’s worth writing about, it’s easy to start feeling as though ‘small’ breaches are unimportant.

This is a similar problem to cybercrime reporting that zooms in exclusively on multi-million dollar ransomware payments because they make exciting articles, leaving victims who faced more modest blackmail demands feeling as though they don’t count, even though they’re probably less likely to survive a ransomware attack than a bigger, richer company with the resources or insurance to get back on its feet.

The burning question, therefore, is: “What we should be doing collectively to stay ahead of the ‘better and faster’ attacks from data thieves, as we seem to be able to do with better and faster attacks in, say, the field of cryptography?

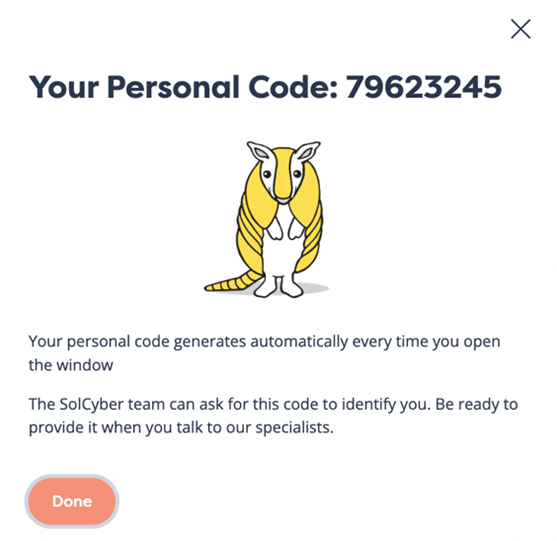

“Tools alone,” as company mascot Amos the Armadillo likes to say on the SolCyber website, “don’t cut it.”

One part of the answer is that we need to change our expectations, our demands, and our actions as digital citizens.

Giving up on privacy should simply not be an option: it’s time to put the humanity and the humans back into data distribution, data collection, and data commercialization.

As Constella’s research suggests, half of the problem in the NPD breach was that a huge amount of real-world data on real-world humans was automatically scraped and collated, but not looked after properly.

The unspoken problem with the other half of the data is just how inaccurate it seems to be.

The fact that its inaccuracy will probably prevent criminals from using it directly for identity theft isn’t a cybersecurity achievement – it’s nothing more than a stroke of good fortune.

Let us not forget that this inaccurate data was collected and indexed without asking and then sold to businesses to help them automate decisions that could affect each subject’s livelihood, chances of employment, acceptability as a customer, and more.

Distressingly, the NPD breach made cybersecurity headlines recently not because it was unusual or even unexpected.

Data protection seems to have become a custom, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet might have said, “more honor’d in the breach than the observance”, and NPD’s blunder was apparently deemed article-worthy not directly because of the breach itself, but because of the announcement of a class-action lawsuit many months after the breach happened, and months after the stolen data was first offered for sale on the dark web.

This makes the question “What to do?” much harder to answer than usual.

Putting a freeze on your credit files, as Brian Krebs explains, is an obvious immediate response, but it deals with one symptom of this breach, not its causes.

Now read Part 2, where we look at some of the things that legislators, regulators, end users, data collators, data consumers, and the greater internet community can do to make our collective defense against data breach problems better and faster…

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image by kirill2020 via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.