What if we all adopted a human-centric cybersecurity culture anchored in value and quality, instead of an automated race-to-the-bottom predicated on cheapness and quantity?

We suspect that’s what you want, and we know it’s what we want, so what can we do to bring everyone else along with us?

Last week, in Part 1, we dug into a megabreach of personal information that probably affected between 100 million and 200 million Americans, with a mixture of home addresses, emails, phone numbers and social security numbers (SSNs) stolen in the incident.

The data was originally stolen, it seems, back in 2023, and offered for sale on the dark web for several months at a price of $3,500,000.

It was ultimately dumped where anyone who knew where to look could download it, and many people have now done just that.

Not all of it was current or accurate, with researchers suggesting that about 10% of the data was for people born between 1900 and 1930, and various people who looked up their own data reporting that it was out of date or wrong.

At a guess, however, as much as half the adult population of the US was needlessly exposed to stalkers, scammers, spammers and identity thieves.

The good news, if you can call it that, is this wasn’t a breach at an official organization such as the Social Security Administration (SSA) itself, which issues SSNs in the first place.

In other words, it wasn’t a fundamental institutional cybersecurity failure by an official body that we have no choice but to deal with and trust to keep our data to itself (there’s understandably only one SSA, one IRS, one Passport Agency, and so on).

The data was stolen from a boutique private company in Florida going by National Public Data, or NPD, run by a former actor and video film producer called Sal Verini.

In fact, National Public Data was just a trading name (a doing business as name, or d/b/a for short) for Verini’s business entity Jerico Pictures, now apparently lying low since news of the breach broke:

The bad news, and you can definitely call it that, is the worrying question of why, or perhaps how, hundreds of millions of Americans chose to share information as personal as their home addresses and SSNs with a business such as NPD.

You might imagine that this could happen at a country-wide financial services company trying to comply with know-your-customer rules, but even the biggest US banks and lenders don’t have more than 100 million customers.

And employers are compelled to keep accurate personal information about their staff, but even the biggest US employer has far fewer than 10 million staff on its books, some or many of whom live and work outside America and don’t have SSNs anyway.

How on earth did Jerico Pictures d/b/a NPD, which apparently has fewer than 25 staff, come to have a database covering so quite so many people?

What possible reason could NPD have to collect and keep that data?

What would motivate anyone to hand their data over to the company?

The short and simple answer to the last question above, as we discovered in Part 1 is: Nothing.

No one actively chose to entrust their SSNs to this company.

No one was asked if they wanted their personal information to be scraped up in unknown ways from unknown sources, packaged into a database, indexed, and commercialized into an online ‘identity verification’ service.

If you’re on the NPD breach list (and its sheer scale suggests that if you live in the US, you might as well assume you are), you didn’t get to choose whether to have your information collected in the first place; you weren’t consulted about how it would be used; and you weren’t asked which NPD customers should be allowed to see it by paying NPD for access.

To be blunt, even if there hadn’t been a breach of epic proportions that was all over the news recently, we’d still have plenty of questions to ask and answer about whether this is the sort of internet that we want or deserve.

Of course, there is a breach in this story, of an unusually large sort, and we need to concern ourselves with that first of all.

As we wrote last week:

Distressingly, the NPD breach made cybersecurity headlines recently not because it was unusual or even unexpected.

Data protection seems to have become a custom, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet might have said, “more honor’d in the breach than the observance,” and NPD’s blunder was apparently deemed article-worthy not directly because of the breach itself, but because of the announcement of a class-action lawsuit many months after the breach happened, and months after the stolen data was first offered for sale on the dark web.

Even though massive breaches are understandably more newsworthy that smaller ones, they’re not necessarily worse for their victims, for whom the overall danger depends on what sort of information was in the mix that was stolen.

That’s why data privacy controls such as the General Data Protection Regulation in the EU and the UK don’t specify a minimum ‘size’ for a breach. (GDPR really is a singular Regulation, not a plural, although it covers seven Principles and is divided into 99 Articles.)

That doesn’t mean size is irrelevant.

The number of victims affected by a breach, combined with the level of risk to which each victim was exposed, may affect the severity of any penalties imposed by the regulator.

But a breach is a breach is a breach, whether attackers access a handful of credit card details from this afternoon’s sales at your coffee shop, or steal a giant database containing the SSNs of hundreds of millions of Americans that you scraped up without their consent or knowledge over a period of months or years.

And this brings us to the next question in the chain.

Why do we seem collectively unable to cut down on the breadth and depth of breaches?

The fact that “we’re collecting and processing much more data than before”, that “we’re storing more data in the cloud”, and that “we’re making research and investigation easier and more democratic by putting data online” aren’t really explanations for why breaches seem to be more frequent and more dramatic than ever.

They’re excuses, perhaps, but they aren’t justifications, because other fields in cybersecurity have stayed largely on top of the Bad Guys despite all these factors.

In Part 1, for example, we looked at the field of cryptography, where attacks for unscrambling secret data have consistently become more dangerous and easier to pull off as computers have become faster.

But these ever-faster attacks have, by and large, been matched by ever-stronger defenses, which have evolved precisely because of the known risks of better attacks.

For the most part, cryptographers and users of encryption have not only kept up with but pulled ahead of cryptographic hackers and crackers.

We also looked, back in May 2024, at a branch of cryptographic research known as PQC, short for post-quantum cryptography, which aims to provide ongoing defense against attacks based on a type of crypto-cracking computer that doesn’t actually exist yet, and that we might never even figure out how to construct.

Why haven’t we done something along those lines to keep up with and get ahead of the challenges posed by data breaches?

Just as importantly, why haven’t all of us become better at dealing with breaches when they do happen, and more honorable in our responses? (To be clear, some companies do respond honorably, which is good news, but ‘some’, or even ‘many’, is not the same as ‘all’.)

For example, even though the data involved has been acquired and reviewed by numerous researchers, NPD’s official breach response [checked 2024-09-02T13:00:00Z] includes the dismissive comment below (our emphasis in bold).

You don’t need to be a grammarian to notice that this is written in the passive voice (‘it is believed’, instead of ‘this happened’), and hedged with hypothetical statements (‘a bad actor was trying to hack’ instead of ‘unknown criminals succeeded in hacking’):

There appears to have been a data security incident that may have involved some of your personal information. The incident is believed to have involved a third-party bad actor that was trying to hack into data in late December 2023, with potential leaks of certain data in April 2024 and summer 2024. We conducted an investigation and subsequent information has come to light. […] The information that was suspected of being breached contained name, email address, phone number, social security number, and mailing address(es).

The US Congress (the American Parliament, in British and Commonwealth English) certainly noticed the inadequacy of this ‘report’, writing bluntly and directly to Sal Verini to offer its opinion on the company’s behavior:

Given the seriousness of the matter, your company’s website has yet to provide a substantive explanation about the self-described security incident. […] National Public Data’s lack of transparency about the cyberattack is staggering in light of the alleged compromised information and potential harm to so many victims.

The Committee is investigating this matter to better understand the details surrounding the security incident, and its impacts. To assist our investigation, we request an initial briefing as soon as possible, but no later than August 30, 2024. […] Thank you in advance for your cooperation with this inquiry.

Even industry behemoth Apple has an interesting way with words when discussing security fixes for what are known as zero-days, the jargon term for bugs that get discovered reactively because cybercriminals or intelligence services already knew about them and were exploiting them unchecked and un-noticed.

(The term zero-day or 0-day denotes that there were no days during which even the most energetic system administrator could have patched proactively against the hole.)

Apple generally makes comments to the effect that the company “is aware of a report that this issue may have been actively exploited,” even though the rest of us interpret this to mean, “the crooks got there first; Apple has now caught up and fixed the problem, so users are strongly advised to patch right now to do the same.”

Telling it like it is should be a key part of any human-friendly cybersecurity culture.

Many of us have already suffered a breach of some sort, perhaps even more than one, so it’s easy simply to declare that the genie is already out of the bottle, and therefore that there’s no point in worrying about protecting our personal information any more.

You can easily get a new credit card, for example, but getting a replacement SSN is very much harder; changing your address could involve selling your property and getting a new mortgage to move house; and your birth date is an immutable part of the historical record that can never be changed.

And even if you manage to convince the Social Security Administration to issue you with a new SSN, which victims of identity theft are not automatically entitled to do, your new number will of necessity be linked to your old one anyway.

Perhaps giving up on privacy altogether is the most practical approach?

It’s more than a quarter of a century since Scott McNealy, CEO of now-defunct hardware and software business Sun Microsystems, infamously described consumer privacy issues as a red herring, saying, “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

But in an angry and still-relevant riposte back in 2000, the year after McNealy’s dismissive claim, journalist and author Stephen Manes took a firm stance in his Full Disclosure column in popular computer publication PC World:

[McNealy is] right on the facts, wrong on the attitude. It’s undeniable that the existence of enormous databases on everything from our medical histories to whether we like beef jerky may make our lives an open book, thanks to the ability of computers to manipulate that information in every conceivable way. But I suspect even McNealy might have problems with somebody publishing his family’s medical records on the web, announcing his whereabouts to the world, or disseminating misinformation about his credit history. Instead of ‘getting over it,’ citizens need to demand clear rules on privacy, security, and confidentiality.

Manes’s conclusion in that article, now 24 years old, was astonishingly prescient:

We won’t get real privacy or security until we demand it as a matter of law. Enough bad things have happened that the outcry should be deafening. But companies eager to improve their marketing efficiency or make billions selling personal data of questionable accuracy continue to wield immense influence.

And yet, in a cybersecurity world where we now have cryptography that’s stronger and easier to use than ever, safer programming techniques, stronger protections built into our operating systems, faster updates, stricter data protection regulations, faster and more reliable backup services, better network management tools, and more and more cybersecurity vendors selling more and more tools that we’re told are game-changers…

…Stephen Manes’s perfectly reasonable cybersecurity manifesto from the year 2000 still remains to be fulfilled.

Indeed, as we remarked last week, the NPD breach revealed not only that a huge amount of accurate personal information had been leaked, thus putting many millions of unsuspecting victims at risk, but also that a similarly vast amount of woefully inaccurate data was casually and uncritically mixed in with it.

Even if NPD’s data hadn’t been breached, it was nevertheless being commercialized and used by unknown third parties to make opaque yet potentially unreliable ‘trustworthiness’ decisions that could affect individuals’ livelihoods, chances of employment, perceived honesty, access to credit, and much more.

This isn’t an issue that can be approached using the traditional method of ganging up on users and urging them to put a bit more effort into cybersecurity, such as picking proper passwords, taking care when filling in logon forms, avoiding unexpected email attachments, or not clicking on sketchy-looking web links.

This isn’t a user-side problem, but a data brokerage problem.

Data brokers, as companies like NPD are known, are both widespread and popular.

Some collect and commercialize data that was willingly shared by consenting users who were promised that their personal information would be kept safe; others collect data that was shared by users with little choice but to do so, for example because they were required by law to identify themselves accurately.

Once data brokers have your data, the active precautions that you take on your own computer and in your own digital lifestyle can’t directly protect you from a security lapse by the brokers themselves.

If you adopt strong passwords, turn on MFA (multi-factor authentication), install endpoint security software, encrypt all your data at rest and in transit, and so on…

…there’s no sympathetic magic in cybersecurity to cause your own diligence to ‘pervade the ether’ and thereby ensure that data brokers take equally careful and sensible precautions with their copies of your personal information.

We need broad and collective action if we are determined to get on top of data breaches:

The ball’s in all our courts!

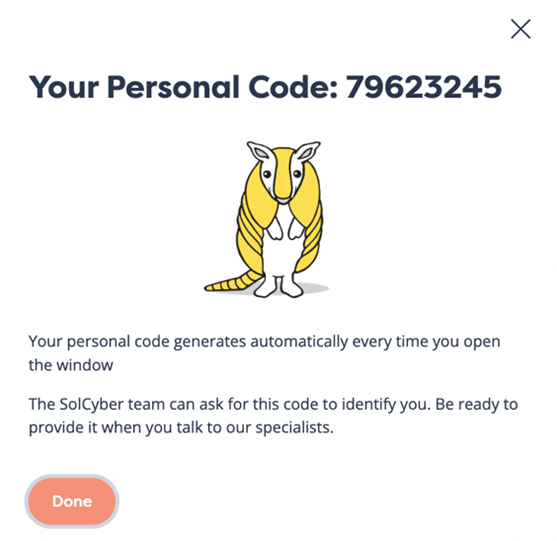

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image by kirill2020 via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.