Over the last two weeks, we published a two-parter about Virtual Private Networks, or VPNs, a network technology that lots of us rely on both for work and for personal browsing.

A reader sent in the following email [lightly edited for clarity]:

I found your VPN articles very helpful because you explained the good and the bad without being judgmental about it.

I know there are dangerous VPNs out there, such as ones that said they kept no logs but did so and then leaked lots of data including passwords, as well as the 911 S5 VPN that sold off your network connection to criminals, which you wrote about recently.

In the second VPN article you briefly mentioned Tor as a form of browser-specific VPN, so I wondered if you could write about Tor in more detail?

I have tried to understand it before but most articles about it either get stuck in jargon by the third paragraph, or they are there to tell you Tor will save the free world and won’t hear a bad word said about it, or they want to tell everyone it is so dangerous you should never use it and if you do you are no better than a criminal yourself.

Can you give us a balanced view so we can figure it out for ourselves?

Sincerely,

Anon E. Mouse

To start with, let’s dig into what Tor is all about.

We’ll start with how it got its name, and the main components of the overarching Tor Project, which pitches itself as “[fighting] every day for everyone to have private access to an uncensored internet.”

Tor, although it’s now a proper noun in its own right and not an abbreviation, started out as an acronym standing for the onion router, a curious metaphor (we can’t think of any other network technologies named after root vegetables) that will become obvious in a moment.

The Tor Project actually looks after three main components that fall under the Tor umbrella:

443 [usually used for HTTPS] on the server called example.com.” The Tor client software then arranges for your traffic to take an encrypted, randomised, zig-zag path through the Tor network to your desired destination, which not only disguises your location but also makes your connection much harder to trace.The good news is that this three-part complexity is neatly hidden for most users, because visiting the Downloading the Tor Browser page from the Tor Project’s website will automatically fetch and install the Tor client and the Tor Browser in one go.

Launching the Tor Browser will automatically load up the Tor client in the background, choose secure settings for you so you don’t need to learn a complex set of configuration instructions first, connect to the Tor network for you, and route your browsing through it.

The browser puts a circuit icon in the address bar that you can use to reveal the relays that your Tor client selected for the current connection:

Firing up the Tor Browser certainly directs your browsing data through a virtual network, using the public internet to bounce your data randomly through a series of Tor relays, and it uses multiple layers of encryption to try to keep your traffic private along the way.

This multi-layered encryption is where the onion metaphor comes from, because onions grow in a series of circular layers, each of which wraps around the one inside it.

In that sense, Tor certainly is a form of VPN, but with some very important differences that are worth keeping in mind.

Some of these differences provide much stronger levels of privacy and security that a typical consumer VPN, but others of them could leave your network activity exposed in ways that a regular VPN would prevent, at least in part:

ping command. This means that even apps that are routing the bulk of their traffic through the Tor ‘onion’ might be leaking other data without you knowing.

As you’ve probably figured out, the first two items in the list above represent risks from which a traditional VPN will tend to protect you, because most VPN software works down at the network level, as though you had plugged a secure network adapter into your computer and disconnected your other network cards.

Tor, on the other hand, works at the application level, so that only some network traffic from some apps goes out shielded, while the rest follows its regular, unprotected path.

But last three items in the list above provide a type of privacy protection that a one-stop VPN service can’t.

As we demonstrated in Part 2 of the VPN article series, choosing a consumer VPN to secure your internet access will stop web services such as shopping sites and ad-delivery networks from seeing the true location of your home network or your mobile phone.

But diverting your traffic from your own ISP to a VPN provider is really just swapping one ISP for another.

Either your ISP or your VPN service (or both, if you don’t use the VPN for everything) is always in a position to identify you uniquely, and to accumulate an extensive record of your network traffic along with the destination servers to which you sent it.

Even if they can’t see the details of the data you exchange, for example because you are browsing over HTTPS, your ISP or VPN nevertheless gets plenty of ‘data about your data’, known in the jargon as metadata, including your network flows, which form a record of how much you said, and when, and which computers you said it to.

Tor makes even this sort of high-level snooping much more difficult, not least because one commercial entity doesn’t get all your metadata.

On most occasions that you visit a new site over the Tor network, you arrive via a different Tor exit node, probably run by a completely different individual or organisation, in a different country, with its own rules about collecting, logging, analysing and sharing any data. (By default, Tor tries to log enough information to be useful for troubleshooting, but not enough for subsequent surveillance or tracking.)

At this point, we need to take a slight technical detour to describe how and why Tor’s three-hop circuits provide better privacy and anonymity than a VPN, or even than three commercial VPNs in sequence.

Firstly, a new Tor circuit doesn’t use traffic relays from the same provider every time, which is unavoidable even if you chain three different commercial VPNs together.

This makes it harder for rogue operators in the Tor ecosystem to conspire to track you with any fidelity, given that your own Tor client chooses the nodes for each circuit in an unpredictable way.

Secondly, the Tor client, which picks the nodes for each circuit itself, does three layers of ‘onion encryption’ first, each one wrapped around the previous layer, before sending your data to the first relay in the circuit.

Each relay can only strip off the outermost layer of encryption, so that each relay only gets access to a subset of the information need to reconstruct your traffic and its network flow:

Data coming back is treated in a similar way, with the exit node wrapping any replies in three new layers of encryption and handing it back to the middle relay node, which is as much as the exit node knows about the return path.

Each relay in the circuit knows only the location of the two nodes on either side of it, with the middle relay making it hard for the entry guard (which knows where you are) and the exit node (which knows where you went) to collude to unmask your full network flow.

As we mentioned above, Tor also supports an special and unusual way of connecting known as a hidden service, denoted by a special web-style name that ends with the text .onion.

This creates a level of privacy that a chain of traditional VPNs can’t, no matter how long that VPN chain might be.

Simply put, hidden services hook together two three-hop Tor circuits ‘back-to-back’, in a six-hop connection that not only protects the server from knowing who or where the client is, but also protects the traffic in the other direction, so that the client can’t figure out where the service is, either.

Perhaps more importantly, there’s an additional layer of end-to-end encryption in every hidden connection, because the Tor proxies at each end of the back-to-back circuits agree on a secret session encryption key while the connection is being set up.

(A three-hop Tor circuit that exits onto the regular internet has a Tor proxy at one end but a regular server at the other, so it has no practicable way of negotiating full end-to-end encryption.)

The hidden service protocol is too complex to explain here, so we’ll just note the following: the hidden service itself chooses three separate three-hop Tor circuits of its own as a redundant way of notifying the Tor network where it can be reached; your browser, when it wants to connect, opens an outbound Tor circuit to a node that’s dubbed as rendezvous point, as we mentioned earlier; and the hidden service creates its own outbound Tor circuit to and from which the rendezvous point shuttles your browser’s traffic.

As this diagram [lightly modified and annotated] from the Tor Project’s own full explanation shows, the client’s circuit knows only where the server’s circuit ends, but can’t find out where it starts, and although the server can return data to the end of the client’s circuit, it doesn’t know where the original request started:

Because a hidden service connection starts and terminates at a Tor proxy in both directions, your traffic never emerges onto the public internet at all, as the image above denotes by wrapping all the communication inside a green ‘onion’ outline, so there’s no need for an exit node anywhere in the circuit.

The end-to-end encryption starts in the local Tor proxy at the browser’s end of the link, and doesn’t get stripped off until the data has traversed the Tor network and reached the Tor proxy on the server where the hidden service is running.

The browser side knows only that it has asked to connect to a server with a name such as pxq2lo2t25l2s7nsvgbnzoj2l2m3vl4mi5xku6h5mqatjcwdybutaqyd.onion, but not where that server actually lives on the internet; likewise, the hidden server knows only that data arrived via a Tor circuit, but not where the visitor’s traffic originated.

Generally speaking, neither end can give the other away, unless either or both of them make an operational blunder, or someone finds a data leakage bug in the Tor software.

As you can imagine, all of this privacy and anonymity comes with a cost; indeed, with several costs.

Those costs aren’t a purchase price or a subscription fee, because the Tor software, including both the proxy and the browser, is free and open source, and the Tor network is run for free by volunteers.

The most obvious cost is performance, given that accessing a regular web server, where the server itself is neither anonymous nor hidden, redirects your data through three randomly-chosen relays that could be all over the globe, run by volunteers who aren’t earning money from the bandwidth they donate, and who are sharing that bandwidth amongst anyone and everyone using Tor:

Hidden circuits juggle your traffic forwards and backwards through six Tor relays and eight encryptions-and-decryptions even for the simplest request, and repeat that process for every reply, making them slower still:

Other problems include:

SOCKS proxy protocol that Tor uses to redirect your traffic, but also need to be configured to talk via Tor and nowhere else. Some apps can’t be configured to use Tor at all; others may use Tor some or most of the time, but unexpectedly access the internet directly and give you away when you don’t expect it.Always remember: Tor doesn’t magically make you anonymous all on its own; the Tor network and its hidden services may expose you to online dangers you would otherwise not have experienced, because the Tor has been keenly embraced by the cybercriminal underground; and Tor may give you a ruinously false sense of security if you don’t use it wisely and correctly.

In three simple words: READ THE MANUAL!

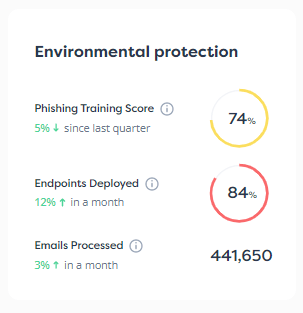

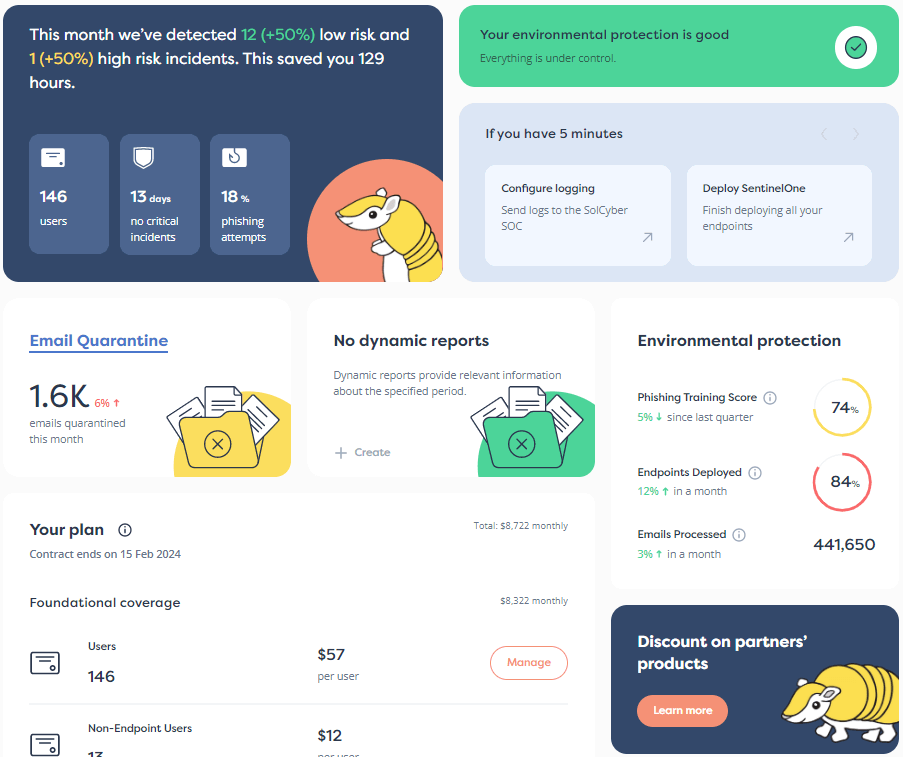

Why not ask how SolCyber can simplify your cybersecurity journey?

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of onions by Lali Masriera via Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.