Different cybercrime groups have different interests, and different aims.

Some of them don’t probe your network or trick your users in the hope of initiating a huge campaign of intellectual property theft, or of unleashing a giant ransomware attack.

Some of them just want to find out how they could carry out those attacks if they wanted to, and then to sell that information on to cybercriminals who do.

Last week, we looked at supply chain attacks to understand just how much devious dedication some cybercrooks put into their criminality.

We revisited the astonishing story of Jia Tan, the nickname of an inscrutable attacker who spent at least a year up front ingratiating themselves into the open source community in the general field of file archiving and compression – miles away, you might think, from remote access, cryptography and network security.

But Jia Tan’s apparent dedication to data compression was a cunningly disguised, long-term effort to compromise the security-conscious OpenSSH remote access toolkit on Debian-style Linux servers.

Debian is a large and generally well-managed community Linux distro, which uses its own modified variant of OpenSSH, which uses a mainstream system management toolkit called systemd, which uses a tiny project called XZ Utils for data compression.

Deliberately and directly injecting a remote access backdoor into the official source code of the OpenSSH project itself, or into Debian’s variant of it, or into the widely-used systemd tools, would probably be very difficult, because you’d need to trick every single sceptical expert in those open-source communities into believing that your weird and suspicious changes were in everyone’s interest.

Jia Tan therefore decided that helping out in the archiving and compression community for a year or so to create a track record of apparent helpfulness, followed by months of apparently selfless ‘dedication’ to the understaffed yet widely-used XZ Utils project, would be a much easier way to slither into the supply chain.

The OpenSSH code remained untainted, as did the systemd code.

Instead, Jia Tan compromised the unassuming XZ Utils decompression code tucked in at the bottom of the pile, not to booby-trap the decompression process, which still worked just fine, but to booby-trap OpenSSH’s own remote login process indirectly.

That login process was turned into what’s known in the jargon as an unauthenticated remote code execution backdoor, which means just what it says, and is at least as terrifying as it sounds.

Two cautious years, effectively undercover, for one exploitable hole, though what a hole it was!

Fortunately, Jia Tan’s treachery was thwarted before any real harm was done, because a security-conscious Microsoft software engineer called Andres Freund stumbled across the rogue code and sounded the alarm before most Linux servers had received the poisoned update.

Sadly, if that is the right word, not all cyberattacks require so much long-term planning and such careful ‘sleeper agent’ duplicity.

Some cybercriminal gangs seem to arrive, apparently from nowhere, in network after network, working their way into a position from which they can attack every single computer (or as many as they can find and access without getting spotted) at the same time.

Often, these criminals are part of a ransomware gang, and their aim is to create so much operational disruption by stealing and scrambling critical data that they can demand enormous blackmail payments for what they smugly refer to as “post-paid penetration testing services.”

As you probably know, many ransomware groups these days use what the legitimate business world would probably call a franchise or affiliate model.

A small core group of criminals creates and hands out new malware samples for each attack, handles the decryption keys that victims are blackmailed into buying, and keeps track of the pseduoanonymous cryptocurrency payments made by desperate victims.

Their affiliates, recruited on underground cybercrime forums, do the actual network attacks, the data stealing, and the file scrambling that leaves their victims staring down the barrel of a blackmail demand.

By keeping tight control over the decryption keys, these core crooks prevent their ‘affiliates’ from simply doing deals with their victims directly and running off with the money. (The core crooks typically take 30% of everything paid in, or at least of everything they say was paid in.)

The front-line attackers therefore don’t need to be cybersecurity specialists, elite programmers, malware researchers, or exploit developers.

The core crooks provide the malware samples, so they don’t need, and aren’t looking for, programming expertise or reverse engineering skills in their ‘franchisees’.

What the core crooks want is to attract partners-in-crime who are willing and able to go for network-wide attacks every time: affiliates know that the fewer computers on a network they miss in their attacks, the harder it is for the victims to recover on their own.

Affiliates who know how to track down backups and ruin them; how to use virtual machine (VM) consoles to get into every running guest VM on every server and scramble them all; how to figure out cultural niceties such as the naming conventions for accounts, computers and filenames so they can fit in quickly and unobtrusively; how to build a network map as good as or better than you have yourself; and how to make subtle but critical modifications to your chosen system-wide cybersecurity settings…

…they’re the sort of people whom the core ransomware criminals want to attract.

History suggests that some affiliates do spectacularly well out of their sysadmin skills (unless and until they get caught) by joining multiple ransomware gangs at the same time, and pulling off attack after attack for each one.

In 2022, for example, a Canadian government IT employee turned cybercriminal by the name of Sébastien Vachon-Desjardins was convicted in the US for his role in hundreds of ransomware attacks, including single-handedly carrying out an estimated one-third of the attacks associated with the infamous Netwalker cybercrime group.

Netwalker notoriously targeted organisations such as hospitals and schools; is said to have gone after more than 400 victims in more than 30 countries; and apparently raked in at least $40,000,000 in blackmail payoffs.

Vachon-Desjardins pleaded guilty and was given a 20-year prison sentence, with the judge apparently telling him that he would have received a life sentence were it not for his guilty plea, given the wide and devastating impact of his self-serving criminality.

In a previous case brought against him in Canada, he had already received a seven-year sentence for ransomware attacks against 17 different Canadian companies.

The Canadians almost immediately released him from prison, but only so he could be extradited to the US; on being deported after finishing his 20 years, he will return to prison in Canada to see out his seven-stretch.

When caught in Canada, Vachon-Desjardins was found to have $28 million in Bitcoin and $500,000 in cash, all of which he agreed to forfeit as part of pleading guilty.

If Vachon-Desjardins indeed carried out 33% of Netwalker’s estimated 400 attacks himself, apparently over a period of less than a year (the first attack documented in his US trial took place at the end of April 2020; he was arrested in Quebec, Canada, when his ill-gotten gains were seized, in January 2021), then he managed to ransom more than 130 networks in that time, or approximately one every two days.

Cybercriminals such as Vachon-Desjardins who have decided that their ‘career ambition’ is to take over other people’s networks, stealing and scrambling data as a way to extort money, therefore generally don’t have enough time, even if they have the expertise, to do the reconnaissance or the exploit development needed to figure out a reliable way in to start with.

Instead, they can buy, rather than build, what they need, by finding a willing seller on the dark web whose penchant is acquiring and dealing in information on how to get into other people’s digital lives.

These criminals are known in the jargon as Initial Access Brokers, or IABs for short, an unfortunate name that makes their activities sound like a legitimate career choice, but they are more bluntly described simply as cybercrooks who enable other crooks to break-and-enter in the first place.

The information IABs sell typically includes a wide range of ready-to-use attack enablers: passwords for online accounts containing corporate data; access to remote login portals such as VPNs; details of exploitable online devices that haven’t yet been patched; outdated or incorrectly configured systems that were supposed to have been shut down and retired but never were; and more.

There are many different sources that criminals can use to winkle out these attack enablers, including:

Cyberattacks aren’t always immediately preceded by hostile surveillance activity aimed at finding a way in.

Similarly, signs of hostile surveillance may apparently peter out and not immediately be followed by a related attack, because the criminal groups involved in each of these stages may be completely different.

Initial Access Brokers typically acquire ‘how to get in’ information from one set of sources, either through their own work or by buying it in themselves, and then negotiate to sell some or all of that information on to attackers who are willing to pay for what amounts to access-on-demand to victims of their choosing.

As you can imagine, this not only makes attacks quicker and easier even for non-technical cybercriminals to initiate, but also serves to decouple the various stages of the attack, thus making them harder to detect in advance or to investigate and unravel after the fact.

Here are some tips to defend yourself:

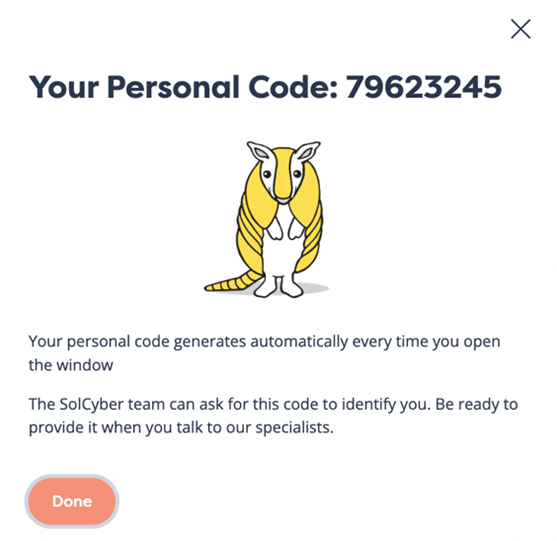

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image by @moneyphotos via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.