1987 had shoulder pads, mullets, and emailed malware.

The first of these threats (or perhaps “unseemly risks” is a more balanced phrase) spontaneously vanished in the 1990s; the second has recently made a modest comeback; but the third one never went away.

This holiday season, as much as any other, we’re therefore unable to think about cybersecurity without yet again recalling George Santayana’s famous words from 1905.

By that time, the transformation of America by the industrial revolution, which had been surprisingly swift, had clearly become permanent and irreversible – ships made entirely of metal! electricity! arc welding! high-rise buildings with elevators! the telegraph! unbelievable bridges that made you forget Manhattan was an island! railroads! mail-order catalogs! a miracle building material called aluminum! carriages that moved without horses! photographic pictures! heck, moving pictures! patent medicines that literally made you glow in the dark, until you could glow no more!

It seemed like a world in which the bounties and the benefits of science and engineering would never end, yet Santayana was minded to warn us all:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

If you’re a LinkedIn user and you’re not yet following @SolCyber, do so now to keep up with the delightfully useful Amos The Armadillo’s Almanac series. SolCyber’s lovable mascot Amos even does seasonal songs (though he gets other people to sing, because his own voice is rather croaky) urging us not to forget those people who work through the holidays to keep us safe online:

Even if you know all the jargon yourself, Amos will help you explain it to colleagues, friends, and family in an unpretentious, unintimidating way.

Let’s rewind 38 years to December 1987, a time when very few people had online computer accounts.

Nevertheless, those fortunate few, such as users of IBM’s VM/CMS operating system, popular in business and academia, were understandably keen on the possibilities of email and what was effectively instant messaging.

VM/CMS made email surprisingly easy to use, albeit on clunky IBM 3270 text-mode terminals without graphics, mice, pointers, overlapping windows, or any of the niceties we take for granted today.

VM/CMS was short for Virtual Machine Converational Monitor System, an orotund name that captured two vital characteristics that not all computer systems offered their users at the time:

VMs would run more slowly if there were hundreds of users logged on, but everyone would still have the illusion of working on their own computer, at their own pace, in real time.

Students and keen hackers, of course, learned to show up late, or work on holidays, when their favorite terminals in the best spots in the lab would be free and they could enjoy the illusion that the mainframe really was their very own computer.

With few other users online to compete with, their own VMs would run much faster, and much more exciting and challenging programs could be tried out while everyone else slept. (Some things never change.)

VM/CMS terminals were truly interactive and connective, just like today’s internet, but in words, not in pictures.

Users had near-real-time online interaction, one-to-one and in groups, but without all those AI-generated “bus going over speed bump at 300mph” videos that we suffer from today.

There weren’t any “don’t you wish you were this self-proclaimed cryptocoin influencer living it large in Dubai” messages, either, or any clicks-likes-and-shares anxiety.

But there was malware, albeit that this sample was apparently created by a bored student thinking they were funny, rather than by money-grabbing cybercriminals or rogue operators taking bribes from their own or a foreign government.

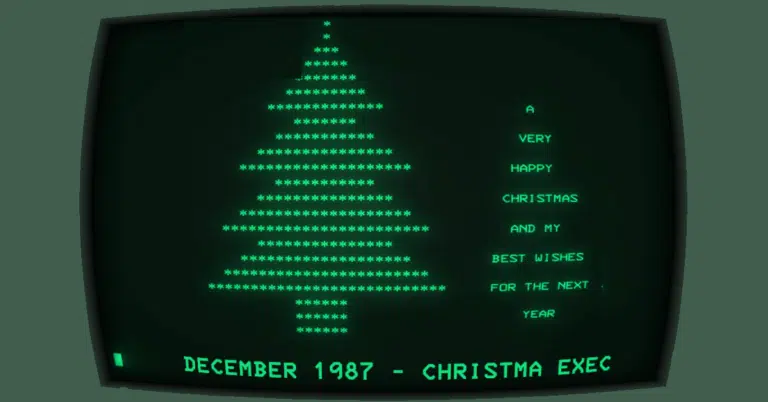

The so-called Christmas Tree Worm of December 1987 was the first network malware that not only spread by email on purpose, but that also actively and automatically retransmitted itself to as many people as it could, including people on other VM/CMS systems elsewhere on IBM’s networks.

The malware hid its sleazy side with a cheery decoy message that filled the screen, distracting victims from its background misbehavior in a way that malware writers have copied ever since:

*

*

***

*****

*******

*********

************* A

*******

*********** VERY

***************

******************* HAPPY

***********

*************** CHRISTMAS

*******************

*********************** AND MY

***************

******************* BEST WISHES

***********************

*************************** FOR THE NEXT

******

****** YEAR

******

Even in 1987, IBM’s networks had a huge global reach, and although the worm outbreak apparently started at a university in Germany, it ultimately spread throughout the world.

It blasted its way through EARN (the European Academic Research Network), BITNET (its North American cousin), and, unavoidably perhaps, IBM’s own VNET, the IBM staff network that just happened to be the backbone of EARN, BITNET and others that were layered on top of it.

Strictly speaking, it wasn’t the CHRISTMAS worm, it was CHRISTMA, and more precisely it was CHRISTMA EXEC.

VM/CMS programs (the divisive word app had not yet been invented) had names of up to eight characters, followed by the suffix EXEC to denote an executable file, much like the .EXE extension on Windows programs to this day.

Loosely speaking, you’d receive a message, probably from someone you knew, possibly someone you knew well and communicated with a lot.

The message was actually a program, written in a popular IBM scripting language of the day with the delightful moniker of REXX, short for Restructured Extended Executor, a swashbuckling name that sounds so much richer in possibilities than the dominant languages of today.

Perhaps the most popular language today is JavaScript, which got its name as a dubious marketing trick to make it sound like the entirely dissimilar language Java, which was already well-known. There’s also Python, named after a satirical TV show that was considered daringly countercultural when it aired, although that was 60 years ago, when fish slapping dances and Norwegian Blue parrots were still unknown, and the Knights Who Until Recently Said Ni did, indeed, still say exactly that. And we now have, of course, the language Rust, named after an astonishingly dangeorus and harmful family of plant diseases.

Programmers might be intrigued enough to study the code, but non-technical users didn’t need to, because the creator of the worm used a splendidly direct social engineering trick that works well to this day.

They simply told recipients, in a cheery comment in the code, what they needed to do:

/*********************/

/* LET THIS EXEC */

/* */

/* RUN */

/* */

/* AND */

/* */

/* ENJOY */

/* */

/* YOURSELF! */

/*********************/

REXX, just like C and C++, uses the special markers /* and */ to denote parts of the program that the computer will ignore, in order to provide helpful remarks that allow you to ignore the code.

Then the message gave the following fateful “advice”, just like modern-day scammers inviting you to open attachments and click [OK], or telling you to scan QR codes so you don’t look too closely at their URLs:

/* browsing this file is no fun at all

just type CHRISTMAS from cms */

If you typed the cheery word CHRISTMAS into your terminal, then VM/CMS happily ignored the redundant ninth character in the word, treating it as though you said CHRISTMA.

The system also automatically knew to look for a file with the suffix EXEC, in the same way that Windows doesn’t expect you to worry about extensions such as .EXE and .DLL, even though you might be more inclined to be cautious when seeing the file’s full name.

The program that had just been emailed to you dived straight into your address book, a VM/CMS file called NAMES that each user would customize to suit themselves.

This “nicknames” file contained, as you will have figured out already, a helpful list of the names and network identities of the very people who would be unsurprised – perhaps even delighted – to receive a digital Christmas card from you.

You can guess how this went down.

If you “viewed” the CHRISTMA “greeting” you’d just received, then everyone in your NAMES file would get a copy, and because groups of friends and colleagues are usually in each others’ address books, a veritable Christmas storm of messages arose almost at once.

If you manged to infect 50 of your close friends and colleagues, and your address appeared reciprocally (as you might expect) in each of those 50 people’s NAMES files, you alone would get 50 messages back from them, in a sort of Ponzi scheme turned back-to-front, such that the earliest participants end up with the worst outcome.

Malware these days tends not to replicate itself, precisely because infection storms of this sort draw far more attention to the attack than simply sending a single customized copy to each potential victim.

But the underlying message is clear.

DON’T TAKE ANY ACTION, CLICK ANY BUTTON, OR EXECUTE ANY COMMAND JUST BECAUSE THE SENDER TOLD YOU TO.

That advice doesn’t just mean the obvious precaution of not installing apps on someone else’s say so.

It also applies to precautions such as:

Have a safe festive season, everyone!

Learn more about our mobile security solution that goes beyond traditional MDM (mobile device management) software, and offers active on-device protection that’s more like the EDR (endpoint detection and response) tools you are used to on laptops, desktops and servers:

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.