If you’re a regular road user, especially if you’re a vulnerable cyclist, people you know will often bid you farewell with a cheery wave and a well-meaning cry: “Ride safely!”

Make no mistake, it’s delightful to be sent on your way with a spot of encouragement of that sort, so don’t let me talk anyone out of doing just that.

But apart from making the rider feel happier, knowing that someone cares about them, how much value does that advice really have?

After all, most cyclists don’t set out to ride unsafely.

In any case, their comparatively low speed and momentum means that their safety is much more likely to be put at risk by carelessness, aggression or unsafe actions by other road users – those carrying hundreds or thousands of times as much kinetic energy.

(As cycling safety experts like to point out, think of how safe it is to walk alongside a train that’s standing at the platform to get to your carriage, compared to how dangerous it is to stand at the platform edge when a train hurtles through the station without stopping.)

In practice, it would be as useful for the person handing out that vehicular advice to take a completely different approach.

For example, they could fling back their head, take a deep breath, and bellow into the passing traffic as loudly as possible: “EVERYONE ELSE DRIVE SAFELY!”

Or they could offer advice along the lines of, “Never, ever, ride a bicycle. Statistics show that although accidents are uncommon, cyclists tend to come off worse, so it’s better to be the one doing the running over than the one being run over.”

Even if we ignore that defeatist attitude, and its logical conclusion that because bigger cars tend to crush smaller ones in collisions we should pursue solutions that favour ever larger and more complex vehicles on safety grounds…

…for anyone who doesn’t have a car, or can’t afford one, or doesn’t have the space to keep one, or any of a range of other reasons, advising them to give up riding altogether doesn’t help at all.

Many cyclists ride because that’s their most effective transport solution, and jumping ship to a car (if you will pardon the mixed metaphor) is not a useful option.

Well, cybersecurity is full of much the same sort of apparently well-meaning truisms, and one that you’ll hear all the time, especially in or around holiday seasons when people are more likely to travel, is, “Beware Public Wi-Fi.”

A few years ago, that advice tended to be more specific, along the lines of “Beware free Wi-Fi,” or “Never use unencrypted Wi-Fi,” but it has now settled into what comes across as a blanket ban on connecting to any network that you don’t run for yourself, by yourself (or that isn’t officially run by your employer, if you are back in the office these days).

That, of course, raises three immediate questions, namely, “Why not? What if I can’t easily manage without it? And anyway, what to do instead?”

Sadly, perhaps, not a few of these Wi-Fi warnings, often reprinted as public-spirited advice in the media, are put forward by cybersecurity vendors themselves, for example by providers of what are known as personal virtual private network (VPN) services, to promote their products as necessary and sometimes even sufficient to make you safe on Wi-Fi networks.

But is that alone enough to keep you safe?

And, for that matter, does it inevitably improve your online security?

It’s easy to assume that the best way to stay ahead of the cybercriminals is simply to keep up with all the new and ever-changing security tools that claim to help.

But what if your supposed countermeasures ultimately make things worse, or at least harder to keep under control, given that they add yet more steps, yet more security processes, and yet more complexity into your online life?

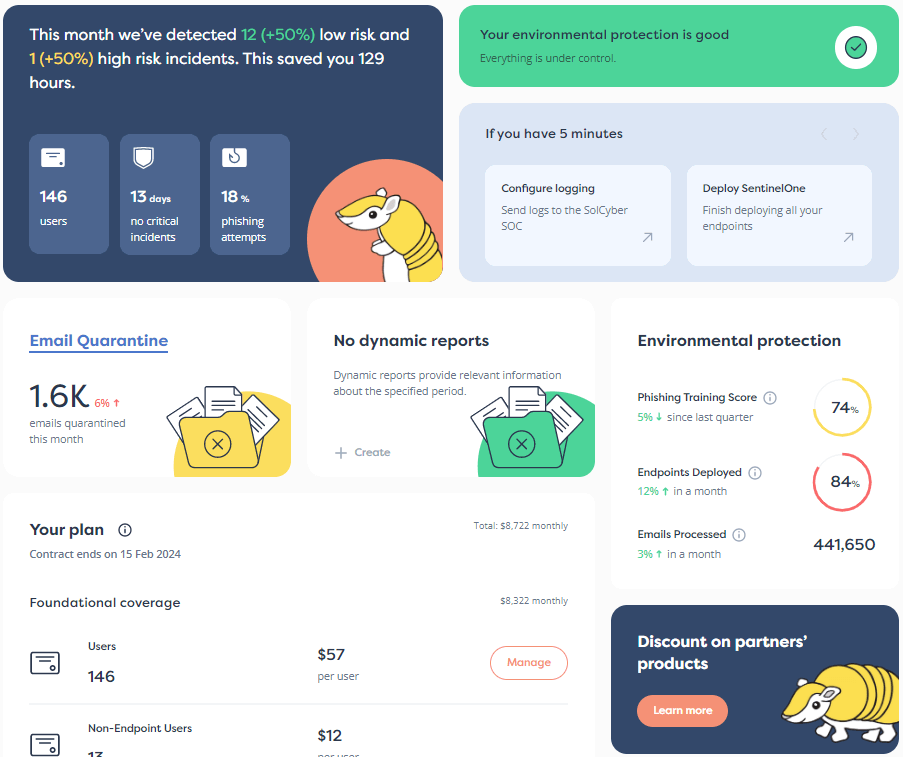

As the main page of the SolCyber website wryly points out: “After 20 years, cybersecurity is the only industry where you buy more stuff, yet remain less certain about your level of protection. This is not OK.”

The truth is that getting to the bottom of online safety, security and privacy, even just for Wi-Fi, is a difficult and ever-changing task.

Do more security tools automatically mean more security?

Perhaps, or perhaps not.

Let’s dig in and take a look, using Wi-Fi as our sample issue.

In theory, a VPN scrambles all your data as it travels between your computer and the VPN provider, which feels as though it ought to provide an extra layer of protection against any snooping or interference.

If you’ve connected via someone else’s Wi-Fi router, for example, then that router is the very first ‘hop’ for any network packets on the way out, and the very last ‘hop’ for any replies that come back, regardless of how far away your intended destination might be.

That certainly brings a bunch of obvious risks when you don’t have any control over that ‘first hop’ router, especially for traffic that is neither encrypted nor integrity-protected.

For example, here’s a sniffable DNS request (name-to-network number lookup) via a free and unencrypted Wi-Fi network, still commonly offered at coffee shops, shopping malls, hotels and so on because it means not messing around with Wi-Fi passwords just to connect to the access point in the first place:

To explain, MAC in the diagram above is short for media access control, a 48-bit (6-byte) tag that most types of network card inject into their network packets as an identifier so that requests and replies on the local-area network (LAN) can find their way back and forth.

In case you’re wondering (I’ve truncated the MAC addresses above for brevity and privacy), the first three bytes of a MAC address often denote the vendor or creator of the network device.

The prefix 74 04 f1 is assigned to Intel Corporation, and therefore suggests a laptop with an Intel chipset; 52 54 00 suggests that the server relaying the DNS reply, or the DNS server itself if it is running on the LAN, is hosted on a Linux virtual sever based on the popular virtualization tools QEMU or KVM.

Whether you use a VPN or not, MAC addresses uniquely, if temporarily, tag your network packets on the LAN. (Once your network packets take the next step on their route, the MACs they contain are replaced with identifiers specific to the network hardware devices in next hop, and so forth.)

In other words, encrypting your network traffic is not enough on its own to protect your privacy online.

If you use the same computer, with the same network card, with the same MAC address, on two different networks, a traffic snooper can still track you between those two networks, even though they might have no idea what you’re saying.

On one hand, you don’t actually need VPN software to shield yourself from this sort of traffic matching.

Modern iPhones and Androids, for instance, can deliberately reprogram your network hardware with a different, albeit consistent, MAC address for each Wi-Fi network you commonly use, which reduces the chances of being tracked by collusion between two different providers, one of which knows who you are and the other of which does not.

On the other hand, VPN software that encrypts all your data may or may not provide this sort of MAC address randomization; you’d need to do your own digging (or to read a report from an independent observer you are inclined to trust) to know what level of device anonymity is in play.

Simply put, just adding more security tools, and trusting yet another security vendor, won’t automatically give you more security.

As we said above: perhaps it will; perhaps it won’t.

In requests like the one you see above, the name of the website you’re interested in (example.com in the screenshot) has travelled unencrypted at least over the LAN, and the answer has come back without any encryption or integrity protection.

Intrusively, this tells intriguing (but not necessarily insightful or accurate) tales about your online activity, without sniffing out what you actually go on to say, if anything, to the sites that are the subject of your computer’s DNS requests.

Even worse, it means that the access point you’ve connected to can easily rewrite the DNS answers that come back in a way that’s hard to spot, if you can detect such tampering at all.

Worse still, that sort of DNS rewriting isn’t automatically a bad thing all on its own: the network operator might have spotted that you were about to visit a known-bad site and diverted you to a warning page instead.

In short, the act of tampering with DNS replies isn’t always and automatically evil, but it’s hard to tell if it was or it wasn’t.

That’s a bit like those heavily scrambled and obfuscated JavaScript programs we investigated in the recent article series Script Malware: When simple things get hard.

In those articles, we saw how malevolent-looking script programs often turn out to be genuine software trying to lie low to resist copying, or to protect a vendor’s intellectual property.

Routinely blocking those weird-looking JavaScripts, like routinely blocking modified DNS replies, might therefore get in the way of real work, even though letting them through might expose you to in-your-face cybercriminality, thus leaving your endpoint security software on the horns of a dilemma.

Clearly, a VPN can help against DNS hacking of this sort by shrouding not only the content but even the existence of your DNS requests across any network, whether it’s free Wi-Fi, your home Wi-Fi, the wired network in your co-work building, or the 5G service from your mobile provider.

However, as the Classical Roman satirist Juvenal famously wrote, in a mellifluous phrase that’s widely known even to those who know no other Latin, “Quis cusodiet ipsos custodes?”

Who will guard the guards themselves?

A badly-managed VPN could make your cybersecurity problems worse, because you’re concentrating all your network traffic through the VPN company’s servers, where the VPN provider unscrambles it for passing onwards.

In other words, you’re pretty much substituting any faith you may or may not have in your local coffee shop’s Wi-Fi provider, or your local mobile phone company, or your local ISP, with faith in a company that may well pride itself in being based far away in a jurisdiction that you don’t get to choose, that you don’t know much about, and that has a very light or non-existent regulatory touch.

The thing with very-light-touch privacy regulations is that they are like double-edged swords: they cut whichever way you swing them, so that although they may shield you from unwanted and unappreciated surveillance, they may also cut you off from any pretence of fair play by, or recourse against, online businesses that operate under their ambit.

Just to be clear: the point of this article is not to challenge the value of services such as VPNs, or to imply that jumping on any old Wi-Fi network whenever you like is harmless enough not to justify any security concerns.

As we’ve already mentioned, it can definitely work to your advantage to add a layer of encryption and integrity protection to parts of your network that you know don’t provide any of their own.

After all, it’s not enough to trust the owner of your local coffee shop, whose knowledge of coffee and how best to prepare and serve it might be second to none.

You also have to trust the Wi-Fi router they installed using the basic instructions that came with it five years ago; and the security updates offered by the ISP that owns or supplied the router; and perhaps also the IT outsourcing company hired to manage the ISP’s routers; and the software supply chain that feeds into the updates delivered by that outsourcing company; and much more.

(Some ISPs not only enable remote access for their own IT company to the routers they supply, whether they make that clear or not, but also provide no way to turn that access off.)

At the same time, however how do you know you can trust any VPN provider that claims to protect you from that coffee shop router, or from your own ISP, or from your mobile provider?

Yet more confusingly, what if your VPN provider encrypts and secures some of your traffic, but not all of it?

So-called ‘split-tunnel’ VPNs are surprisingly common, not least because some services you need to use, whether for business or at home, might not work reliably or quickly enough through the VPN.

The security of some of your traffic might therefore depend on the trustworthiness and competence of your VPN provider, yet the security of the rest of it might continue to depend on the coffee shop, or its ISP, or the ISP’s supply chain, or even on the honesty and integrity of other patrons in the coffee shop while you’re there.

Even if you decide that the answer to “Beware Public Wi-Fi” is to avoid it entirely, what sort of service should you choose instead?

If you decide buy a local mobile phone SIM card whenever you travel to a new country (often the fastest and cheapest way to get online), how much do you know about the terms and conditions of service in that country?

What sort of mandatory surveillance and logging are you are agreeing to?

How do you cancel your service permanently when you leave so that future misdemeanours on that mobile number don’t come back to haunt you?

If you decide to opt for wired connections only, for example at a hotel or co-work site, how will you manage the fact that wired LANs pose similar risks to Wi-Fi, with the annoying difference that almost all wired networks are entirely unencrypted, while at least some Wi-Fi networks provide at least a basic level of safety against casual surveillance by almost anyone in the vicinity?

In short, if you’re willing to “Beware Public Wi-Fi,” especially by avoiding it whenever you can, on the grounds that you can never be sure how much trust to put in access points you didn’t set up yourself, you need to be ready to “Beware VPN Services,” and to “Beware Mobile Networks,” and to “Beware Wired LANs Outside your Home,” too, thus presenting yourself with a much bigger cybersecurity headache than you might at first have thought.

So, if it’s difficult to answer the many cybersecurity questions implied by the single warning to “Beware Public Wi-Fi,” bearing in mind that we’ve looked here at a single DNS request and therefore merely scratched the surface…

…perhaps it’s time to ask for help for your cybersecurity as a whole, from a managed security service provider that is run by humans, for humans?

Avoiding public Wi-Fi while you are out and about is easier said than done, so here are some simple precautions that can help, no matter what extra security software you may decide to use as well:

• Encrypt as much as you can of your own network activity, before it leaves the software that generates the traffic. Don’t rely only on network-level encryption such as a VPN, because that typically gets stripped off somewhere along the way at the servers of the intermediate provider, and therefore doesn’t provide what’s known as proper end-to-end encryption. If you can, configure your browser using an option you’ll probably find in your settings as HTTPS-Only mode or Always use secure connections. This means that you can’t make unencrypted connections to websites by mistake, and a VPN provider that decrypts your VPN data half-way to its destination ends up with still-encrypted data.

• Consider turning on secure DNS, at least in your browser. You still need to trust the secure DNS provider (e.g. Cloudflare, Google, OpenDNS), but it means that the websites looked up by your browser, which may include controversial sites that you ultimately never visit anyway, and will probably give away a handy list of all the cloud services you use regularly, won’t be visible to your VPN provider or your ISP as you browse. On iOS, this feature is on by default (and can’t easily be turned off); on Android, search Settings for Private DNS Mode, which should be on by default.

• If you have a recent mobile phone, check that MAC address randomization is turned on. As explained above, this means your phone chooses a different, albeit long-lived, hardware identifier for each Wi-Fi network you connect to, which helps reduce the likelihood of you being matched between two different networks, one of which you haven’t shared any personal data with. On iPhones, search Settings for Private Wi-Fi Address; on Android, search for Use randomized MAC.

• Consider turning automatic network connection off. It’s generally OK to auto-join your home network, as long as you’re confident that you have kept your Wi-Fi network password private. Anyone who sets up a rogue network with the same name elsewhere (this is a simple trick to lure your phone or laptop into connecting silently to a fake service while you’re on the road) would need to know your own network password to create an imposter access point that your device would accept. Unencrypted Wi-Fi, or services with shared passwords, such as the ones written on coffee shop walls, are easy to fake. Search for Auto-Join on iPhones and Auto-connect on Android.

• Given that mastering all the complexity discussed here will help you with just one part of just one aspect of cybersecurity, why not find a managed security service provider who can help? Don’t just buy more and more tools and services from vendors who are badgering you to upgrade to close the protection gap that the last product they sold you turned out not to deal with. Find out how SolCyber is built different, and choose a security service where you can always talk directly to a human, and get help with anything.

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image via Felipe López on Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.