The digital cyber-vandals who churned out the first computer viruses liked to tag them with counter-cultural names that they could use for bragging rights.

Sometimes, those names took hold because they were memorable, or because they were unavoidably woven into the visual fabric of the malware.

What else, for instance, could the infamous Tequila virus have been called, given that when it showed itself after three months of quietly replicating, it said Welcome to T.TEQUILA's latest production, and proclaimed BEER and TEQUILA forever?

Often, however, malware researchers of the day went to great lengths to choose names that were deliberately different from what the authors wanted.

Some researchers even took text from the malware, but reversed it as a vague sign of disrespect, which is how the Nimda virus got its unusual name, being the word Admin backwards.

(Quite how often malware writers sneakily reversed their names in advance, in a double-bluff aimed at getting the name flipped back by the anti-virus industry, will never be known.)

Intriguingly, the dilemma of cyber-threat naming is back in the spotlight today, following an imprecation from INTERPOL for cybersecurity vendors to steer clear of the term Pig Butchering, widely used to describe a form of cyber-scam based on bogus investments, notably those involving fake cryptocurrencies.

The name, it seems, comes directly from the scammers themselves, and is an approximate translation of a Chinese phrase that the fraudsters use to refer to their victims.

The metaphor is as odious as it sounds.

The scammers look on their victims as farm animals to be fattened up for slaughter, with the scam ending in financial “butchering”, when the scammers cut contact and run off with every cent that the victims – and perhaps their friends and families, too – have “invested.”

The Chinese connection comes from the fact that the playbook of this scam arose in South East Asia, originally targeting Chinese-speaking gamblers who routinely traveled outside mainland China to visit casinos, which weren’t legal in their own country.

By many accounts, when casinos in nearby countries were forced to close down during the coronavirus pandemic, cybercriminals ramped up their efforts to lure frustrated Chinese gamblers into speculating in cryptocurrencies instead, which is how this crime ended up with the translated name “pig butchering,” even though that isn’t a common idiom in English.

Though originally concentrated in South East Asia, this crime is now truly global, given that it is conducted entirely online, with scammers targeting victims far and wide.

In 2024, for example, the former CEO of a bank in Elkhart, Kansas, was sentenced to over 24 years in a federal prison for embezzling more than $47,000,000 from the bank and putting the money into one of these fake investment scams.

US authorities managed to recover $8,071,038 of the missing money, providing at least some restitution for the residents of the small town from which the funds were stolen, but covering the rest of the loss fell to the FDIC, the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which insures bank deposits and acts as a safety net for bank failures.

INTERPOL, as we mentioned above, would like us to find another name for this crime, arguing that:

The term “pig butchering” dehumanizes and shames victims of such frauds, deterring people from coming forward to seek help and provide information to the authorities.

(Clearly, as the $47 million embezzled from the people of Elkhart, Kansas reminds us, some of the primary victims of this crime are serious criminals in their own right, and sparing them from “dehumanization” and “shame” is probably not high on the agenda of their secondary victims.)

The tricky question, of course, is what phrase to adopt instead for a cybercrime that typically unfolds like this:

The idea, very simply, is to lure the victims into the sort of brief chat you might have with a stranger at the station, or the fellow commuter you end up sitting next to on a bus.

Often, those conversations drift harmlessly into companionable silence; occasionally, however, you find some common interests that you are happy to chat about, such as why you prefer iOS to Android, or how much quieter and more comfortable the new electric buses are.

After all, what’s the harm in conversing casually with someone whom you aren’t planning on sharing any personal data with, and whom you’ll probably never hear from again?

But “pig butchering” follows a deliberately devious path of chat that is neither casual nor random, as the US National Cybersecurity Alliance (NCA) bluntly explains:

• Seemingly accidental or mistaken contact, but the person wants to keep talking.

• Conversation turns to investments in cryptocurrency, gold markets, or foreign exchange.

• Continued, sustained contact to encourage repeat theft.

Crypto investment: After conversing with the target, the scammer will try to persuade them to invest in a cryptocurrency or platform. They may also suggest gold trading or forex (foreign exchange markets). In pig butchering, all these “investments” are fabrications, and the money goes straight into the scammer’s pocket.

Extended contact: The scammer will insist on continued investment once they’ve hooked a victim. They might produce fake charts or even send over small “withdrawals” to convince the victim. Sometimes a target is directed to a fraudulent app that mimics financial platforms like Robinhood or Coinbase. Once the victim catches onto the scam or seems to be tapped dry, the scammer ends contact and disappears.

The fraudulent investment apps that these scammers lure their victims into installing are often surprisingly realistic, copying the look-and-feel of legitimate apps, and linking to “live” websites that appear to list real-time transactions just like legitimate online trading sites, thus giving the impression of a genuine and lively “online market.”

The graphs, of course, are entirely concocted, heading almost continuously upwards, and the balance statements that the app presents are completely fake, showing an “investment amount” that simply doesn’t exist.

Android users can be lured into installing non-Google apps by themselves, because Android allows the use of software markets other than Google Play.

But iPhone users can be targeted too, even though consumers can install apps only from Apple’s own App Store, which is pitched as carefully vetted and safe.

(Malware does get into the App Store surprisingly regularly, but long-running scams that rely on apps are hard to pull off by infiltrating the App Store, because rogue apps get thrown out if they’re spotted.)

One trick involves convincing victims that they are lucky early adopters – much like the investors who managed to get into Bitcoins back when they were just a dollar or so each – and inviting them to sign up for a limited-access app release.

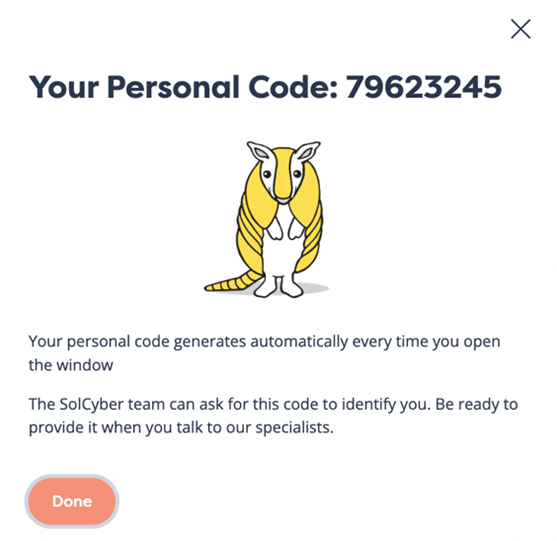

For this early adopter privilege, the scammer will explain, the victim needs to join an invitation-only group of users by enrolling their own phone into the scammer’s Mobile Device Management (MDM) service, as though they were an employee being issued with a work-owned phone.

This gives the scammers a huge degree of remote control over enrolled devices: they can wipe the victim’s phones remotely, for example if they think that the police are onto them; and they can install proprietary “business” applications that aren’t available in the App Store, and that have therefore not been vetted, or seen by by Apple at all.

Even at the end of the scam, when the victim has become suspicious to the point of demanding to withdraw their “investment” in its entirety, the scammers sometimes sting the victim for yet more money, using high-pressure threats and intimidation.

The scammers may seem entirely obliging at first, leading the victim to believe that their payout is about to go through…

…before jumping in to warn the victim that “the government” is now involved, seeking to recover some sort of withholding tax from the total payout, for example 20%, before the rest can be sent.

As suspicious as the victim might be, the scammers temptingly note that even after 20% is withheld, 80% of the imaginary “investment” will be paid out anyway, free and clear of further “government” intervention.

As you can probably imagine, the intimidation comes next, based on a lie that the “authorities” have become suspicious, have abruptly frozen the account, and are insisting that the necessary tax be paid in advance, instead of withheld, so that the victim can “prove” their legitimacy as the owner of the account.

“Don’t worry,” the scammers will say, “Beg or borrow from your relatives – or take an unauthorized ‘loan’ by stealing from your employer – to come up with the tax money, and you’ll immediately get 100% of the ‘investment’ back, so you can return all the money you ‘borrowed’ before anyone notices.”

But if you don’t pay, the scammers turn nasty, with a threat such as, “The government will come after you personally, and they won’t be interested in a 20% tax. The funds are frozen, so they’ll take it all anyway, and then prosecute you for having had the ‘investment’ in the first place.”

The name Pig Butchering reflects very clearly just how much disdain the criminals have for their victims, and just how brutally the criminals want to interfere in, and ruin, their victims’ lives, to the extent of stealing their life savings, and persuading them to plunder the life savings of other people, too.

Nevertheless, INTERPOL wants us to stop using that term, and to use a name that reminds us how the scam often starts in the first place, namely Romance Baiting.

Sadly, that’s not a terribly good name either.

Although these scammers started out by using dating sites as a convenient way of forming non-romantic friendships with possible victims, they now use a wide range of excuses for making their first contact.

These are investment scams, and the scammers may not use dating or romance to “bait” their hooks.

In the words of the NCA:

Scammers often pretend they contacted the potential victim by mistake. While contact can occur through texts [SMS messages], it can also happen through social media DMs, dating sites, or other electronic communications.

By lumping in these scams with old-school romance scams, where the criminals really do bait their hooks by pretending to fall in love with their victims, we’d run the risk that some victims might be sucked in simply because the scam didn’t start on a dating site.

Don’t feel shamed or dehumanized if you are a victim of this type of scam: the name Pig Butchering is a pejorative reference to the criminals who run these scams, not to the victims they prey upon.

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of investment app by Tech Daily via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.