The end-of-year holiday season is close at hand.

This is a period in which people of many different cultures, whether they’re religious or not, spend time with friends and family, exchange gifts, go out together, and typically spend more money than they do during the rest of the year, often including many small transactions in convivial, let-your-guard-down circumstances.

In today’s tap-to-pay world, that usually means touching your payment card or your mobile phone on more payment terminals in more different places than usual, sometimes in places that are crowded, or where you have queued to get to the payment point.

But just how much can you trust those payment points, or, for that matter, the crowds of people around you?

Today’s payment cards are generally much more secure than the swipe-to-pay cards of old, which had no technological protection to prevent them being copied, or skimmed, by criminals.

However, despite the technological simplicity of credit card crimes in the past, those methods did require one important thing to happen.

You had to take your card out, and insert it into a physical device, either the swipe-slot of a payment terminal, or the holding jig in the top left corner of a zip-zap receipt printer, for the data on it to be exposed and copied.

But modern tap-to-pay cards, for all the cybersecurity sophistication that makes them very hard indeed to copy or clone, are designed to work by a combination of movement and proximity.

The card doesn’t know or care whether it’s hidden in your bag, stashed in your pocket, or held in your hand, and it doesn’t actually need to be tapped on the payment device.

Your card needs to extract just enough electrical energy from a magnetic field generated by the payment terminal that it can power up and process one transaction, and it needs to be close enough for its wireless data transceiver (a portmanteau word to denote a radio device that can both transmit and receive) to be within range of the payment terminal.

The radio frequencies used are just over 13 megahertz, which corresponds to a wavelength of just under 25 meters, so the system is known known as NFC, short for Near Field Communication, so-called because it only works when your card is nearer than a tiny fraction of that wavelength – typically at a maximum working distance of 100mm, or 4″.

(In practice, NFC generally needs your card or the NFC chip in your phone to get within about 40mm or 1.5″ of the payment device, but radio waves travel easily through 1½ inches’ worth of clothing, bag material, or wallet.)

For electromagnetic radiation such as radio waves, frequency (f) × wavelength (λ) equals the speed of light (c), which slows down so little in air that we can use the speed of light in a vacuum in our calculations, which is a universal constant. Given that c = 299,792,458m/sec, fλ = c, and f = 13,560,000/sec, then λ = c/f = 299,792,458m/sec ÷ 13,560,000/sec ≈ 22.11m (about 7’3″).

You can see where this is going.

If you can’t lead the horse to water, what if you bring water to the horse?

Today’s contactless payment terminals are not only tiny and cheap, but also easy to sign up for, with numerous online payment services that will provide you with both a device and an internet-based account for processing transactions.

Ironically, perhaps, one well-known online POS (point-of-sale) service provider is right now selling a product that looks like a mobile phone and is advertised as “the powerful, portable POS that fits in your pocket.”

(You can buy one outright for less than it costs to own a basic mobile phone, and then process transactions for a fee of about 2% of every purchase.)

What if a criminal bumps up against you in a crowded bus or train, or in the queue at the coffee shop, or while you’re hanging out at the glühwein stand in the Christkindlmarkt with your chums, or as you’re distractedly browsing for a present in the Really Awesome Gift Ideas For Friends Or Colleagues For Whom You Feel Compelled To Buy An Acceptable Seasonal Trinket Without Spending A Lot Of Money store?

What if you’re standing still, with your payment card in your pocket, and the criminal is providing the movement and proximity needed to trigger an NFC transaction by sidling up to you and bringing a hidden payment terminal towards your card?

What if a rogue employee or vendor sets up up a well-hidden bogus payment terminal right near the real one, rigged up in such a way that you see the expected price shown on the real device, all the while unknowingly paying the same or a different amount into a different payment account, either as well as or instead of the real transaction?

Would it work?

If it did, would you notice, and if you eventually noticed, how long would that take, and what would you do about it?

Welcome to the murky world of Ghost Tapping, a media-savvy moniker that punningly channels Charles Dickens’s infamous character Scrooge and the life-changing Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come.

(Dickens meant present in the sense of something coming up presently, but today that word usually refers to buying and giving a seasonal gift.)

The truth is that hard evidence about the scale of Ghost Tap crimes – unexpected transactions secretly and deliberately triggered by portable or hidden NFC tap-to-pay terminals – is hard to come by.

Informal experiments that I performed a few years ago with friend and then-colleague Matt Boddy (Happy Ghost Tap Season, Matt!) suggested that triggering payment cards in a wallet or backpack without the co-operation of the other person was possible, but difficult enough to be an uncommon or unattractive crime given the need for physical proximity.

We therefore reasoned that it was unlikely to pose a significant problem, and that protecting against other seasonal crimes involving physical interaction should be your highest priority.

Fortunately, protecting your personal property against criminal treachery such as pick-pocketing and bag-dipping also helps to protect against the less likely crime of Ghost Tapping, in the same way that defending against cyberintrusions in general also helps to stop specific classes of attack such as ransomware and data theft.

Any crook thinking of trying their hand at Ghost Tapping is already likely to be be a dab hand (if you will pardon the pun) at stealing actual items, such as mobile phones, laptops, your actual payment and ID cards, or cash, which can quickly be passed to an accomplice to avoid being caught “in possession,” unlike a hidden POS terminal that the criminal needs to carry with them all the time.

Nevertheless, there are simple precautions you can take, or that you may have read about, that specifically guard against Ghost Taps.

One piece of advice that was the same when Matt and I looked into this issue as it is now, is to keep your cards in a radio-blocking cover, and to accept the modest reduction in convenience of extracting the card from its shielding every time you want to use it. (This advice also applies to other contactless cards such as transit tickets.)

Matt decided to buy and test a few cheap products that claimed to stop payment cards being activated unexpectedly, from a trendy-looking metal card-holder box with a hinged lid that cost a few tens of dollars, to a pack of cardboard slip-covers costing well under a dollar each that were lined with some sort of metallic coating.

The idea of buying a bulk pack of cheap slip-covers of this sort is that you can replace them as they get grubby or worn, and hand them out liberally to friends and family if they express an interest in using one.

We found that these products worked as claimed, and that Ghost Tapping was as good as impossible when they were used.

We also tried wrapping cards in kitchen foil – it’s commonly called “tin foil” but it’s actually made out of aluminum – and that worked too. But we didn’t recommend it at the time, and I don’t recommend it now, for three reasons: it’s as annoyingly inconvenient as you probably think; the foil quickly gets torn or scrunched up and stops protecting the card; and when you’re out in public, it unavoidably makes you look like a weird conspiracy theorist instead of simply someone who cares about cybersecurity.

Other advice you may have heard is that Ghost Taps can be prevented if you keep several NFC-chip cards next to each other in your wallet or purse, because they interfere with one another and none of them will work while they are together.

If you don’t have multiple credit cards or don’t want to risk carrying several at once in case you get pickpocketed, which is probably a much bigger risk than a Ghost Tap, then you may have seen suggestions such as keeping your credit card next to an NFC transit card, or inserting a couple of old NFC-based hotel room key-cards in your wallet to run interference.

But this turns out to be an unreliable defense: multiple NFC cards in a stack generally do interfere with each other, but sometimes one of them manages to “win the race.”

In our tests, Matt and I found that when we put two cards together, the card closest to the reader hardly every worked, but the one further away worked surprisingly often.

Intuitively, you might expect the closer card to work better, given that it should power up first and suffer less attenuation through distance. (Electromagnetic signals fade out with the square of the distance they travel, like sound and gravitational force.)

But experience suggests that the more distant card probably powers up only after its closer competitor has started a transaction, interferes with it, and inadvertently clears the way to be the one that works.

Distance gives better prevention than relying on interference, so if you have a backpack, it’s definitely worth keeping your cards and other valuables as deep inside it as you can, instead of in surface pockets, whether you use radio-shielding slip-covers or not.

Doing so, of course, makes life harder for bag-dippers as well, because they have to dig deeper to reach their target.

If anything, the most dangerous device-related risk during the holiday season is being caught unawares and having your phone snatched while it’s unlocked.

We’ve dubbed these phone-grab criminals Balaclava Bandits, because they’re often on fast and silent electric bicycles with their faces shielded to avoid recognition.

They know all the back-street escape routes, and take care to prevent your phone from locking until they reach the next person in the crime chain to whom they hand over the stolen device, at which point your whole digital life may be open to criminal intrusion.

Be sure to read our article dedicated to this rising crime for more advice: Beware the Balaclava Bandits.

Also, check out our deep-dive explainer about modern-day credit card scams that aren’t based on proximity to your card, and indeed don’t need the criminals ever to see your card at all, or even to be in the same country as you:

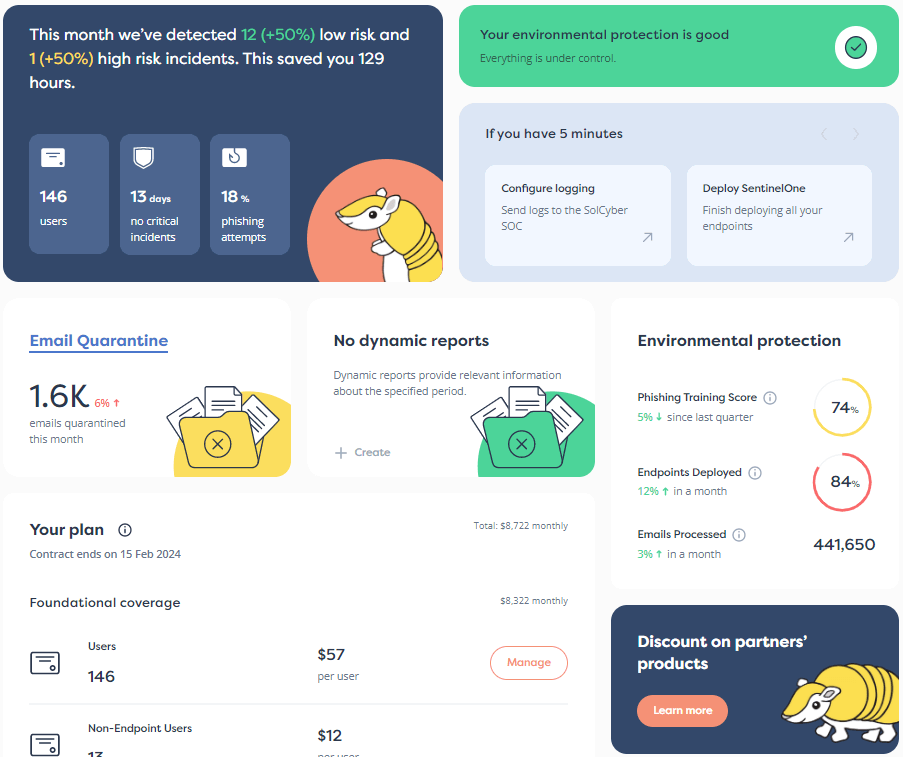

Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.