In 🔗 Part 1, we looked into two issues: how individual threats such as brand new malware strains get named, and how the terminology for various classes of cyberattack come about.

Sometimes, threat names for malware – itself a very handy and self-descriptive name, neatly compressing the concept of malicious software into one word – provide at least some useful information about the threat itself.

But even a carefully-chosen threat name isn’t always enough, as we learned from the examples we used in Part 1, which came from the very early days of program-based and email-based malware, way back in 1987.

The names weren’t perfect even then, when new viruses were rare enough that you could still memorize the entire catalog of known malware if you really wanted to.

Indeed, many threat names in history, even during ultra-widespread malware attacks, have ended up confusingly unrelated to the threat in question.

The notorious and network-crushing Code Red worm in 2001, for example, infected almost every Windows computer where the IIS web server was turned on, which just happened to include a huge number of home users’ PCs, where it was enabled without them realizing.

From every infected computer, it then rapidly attacked other computers all over the world, generating internet-crushing levels of traffic in less-well-connected parts of the globe.

But Code Red was named after the Mountain Dew soft drink of that name, because the first analysts to deconstruct the malware had turned to its high caffeine and sugar content to pep themselves up during a marathon reverse-engineering session.

And the Conficker virus, which was automated zombie malware programmed to spread like crazy until 2009-04-01 and then to start upgrading itself with unknown additional strains of malware, is apparently just a foul-mouthed phrase used, presumably in frustration, by German-speaking analysts who were taking it apart.

Because the uninformative (if understandable) nature of the name wasn’t obvious in English, it caught on, although several mainstream products doggedly called it Downadup instead, which led to widespread confusion amongst users who were convinced they had two super-dangerous malware infections at the same time.

As we mentioned in Part 1, the sometimes mildly regrettable threat names we got stuck with 15 or 20 years ago barely matter these days.

So many new threat samples show up every day that there is not much point in finding a meaningful name for each one, and lots of mainstream threat detection products don’t bother to find even a vaguely relevant name, falling back on uninformative “identifiers” such as Generic and Suspicious instead.

Also, many malware samples today, just like Conficker back in 2009, are programmed primarily to fetch further malware.

Their final outcomes simply can’t be predicted, let alone named, in advance, except to say that those newly-downloaded malware samples could be different in every country, could vary on each sort of device, and could change repeatedly throughout each day.

More manageable approaches to threat naming these days look for terminology that encapsulates the types of cyberattack that each security hole is likely to lead to, thereby describing the sort of immediate side-effects that cybercriminals who exploit that hole are looking to achieve.

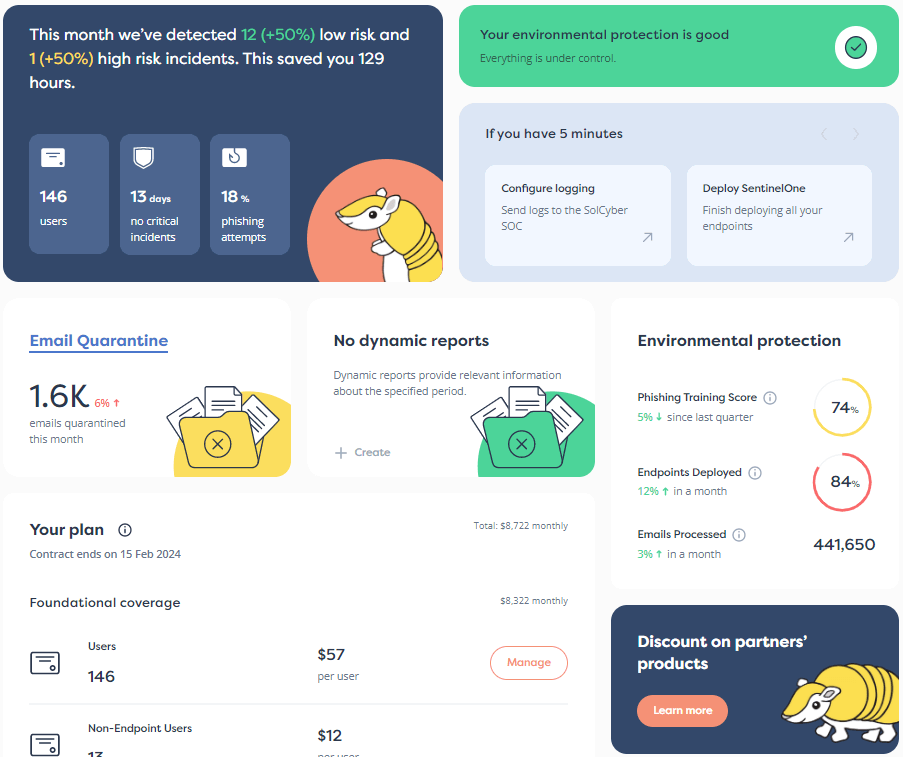

The “big five” terms that you will encounter in security bulletins are these:

GUEST account, and ends up at a more privileged level, typically as the SYSTEM or root user, bypassing any passwords or multi-factor authentication codes that a genuine system administrator would need. EoPs are often tag-teamed with RCEs so that a code execution exploit that gives only minimal system access can then be converted into a take-over-the-whole network attack.As you can see, these threat terms don’t denote attacks by any specific malware samples, or even any broad classes of malware such as viruses, worms, ransomware, spyware, and so on.

Loosely speaking, they’re useful in bug-fix release notes and other security bulletins for denoting the sort of attack that individual bugs or configuration errors could enable.

They also help you to predict the sort of attack symptoms that you, or your SOC (security operations center) team, might look out for if the listed bugs or configuration flaws are ever exploited, and help you choose the sort of proactive cybersecurity precautions that are likely to help the most.

Of course, threat categorization isn’t as simple as knowing the five classes above.

A US non-profit called MITRE maintains a popular framework called ATT&CK (pronounced att-ack), which aims to maintain a well-documented taxonomy for classifying cyberthreats (individually and in categories), attack techniques, and attack groups, by which we mean the various cybergangs, threat actors and state-sponsored operators who carry out those attacks:

MITRE ATT&CK is a globally-accessible knowledge base of adversary tactics and techniques based on real-world observations. The ATT&CK knowledge base is used as a foundation for the development of specific threat models and methodologies in the private sector, in government, and in the cybersecurity product and service community.

If you’re getting started in cybersecurity and you are keen to get on top of the sort of jargon you will read and perhaps write in technical reports, the ATT&CK framework is a useful toolkit.

(Cybersecurity jargon has its place as a compact way for experts to share technical details without using the same lengthy terms every time, provided that everyone can agree on the same vocabulary.)

Unfortunately, there’s an awful lot of ATT&CK terminology to learn, or at least to be aware of, thanks to the breadth, depth, speed, power and complexity of today’s internet, and the fact that we’re still struggling to get the basics of cybersecurity right, 24 years after the Code Red worm, and 35 years after the first ransomware.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE:

You can also watch this video on YouTube with more video controls, including speed-up.

The ATT&CK threat matrices (there are many charts, handily interlinked) and the semi-official nomenclature they introduce are not for the faint-hearted, as suggested in the image above, with a sprawling array of terminology and a curiously eclectic and incomplete list of threat names.

Similar complexity exists in the naming of threat groups, where different organizations have used a variety of naming tags over the years.

Some US organizations, for example, have used the suffix (or family name, if you like) Bear for threat actors believed to be associated with Russia, including the long-running and well-known nickname Fancy Bear, which dates all the way back to 2004.

Unfortunately, MITRE calls this group APT38 instead, and lists a dizzying array of what it called “associated groups” for that name. though it’s not clear if these are alternative names for the same gang, a list of other groups that might be related merely through a possible connection to Russia, or a collection of threat actors of unknown origin and motivation who use similar techniques:

[APT28’s] Associated groups [are]: IRON TWILIGHT, SNAKEMACKEREL, Swallowtail, Group 74, Sednit, Sofacy, Pawn Storm, Fancy Bear, STRONTIUM, Tsar Team, Threat Group-4127, TG-4127, Forest Blizzard, FROZENLAKE.

Microsoft, in contrast, uses its own threat designators based on conditions that generally denote bad or dangerous weather.

Some of these family names have vague associations with the part of the world that the threat actors are assumed to inhabit, such as Sandstorm for Iran and Typhoon for China.

Other names are used to denote cybercriminals with similar motivations but with unknown origin, and the generic word Storm is reserved for “groups in development,” however that is determined:

Although family names tend to suggest an active working relationship between groups, the family names actually tie groups together largely by location or by motivation.

Apparently connected groups could, in fact, be competing for financial gain, or working towards different or unrelated social and political aims.

Nevertheless, Microsoft argues that its naming scheme is helpful, claiming that:

We offer a more organized, articulate, and easy way to reference threat actors so that organizations can better prioritize and protect themselves. We also aim to aid security researchers, who are already confronted with an overwhelming amount of threat intelligence data.

We’ve used a two-part article to dig into the complexity of threat names, threat naming, and threat identification…

…and, to be honest, we’ve really only scratched the surface, as we saw from the graph in Part 1 showing the enormous rate at which new malware samples show up, and as we saw above from the screenshot of just one of many MITRE ATT&CK threat matrices, where we were able to squeeze just 25% of the simplified version of the chart into the image.

We didn’t have time to look into various other lists and taxonomies of threats and vulnerabilities, such as those from NIST (US National Institute of Standards and Technology), OWASP (Open Worldwide Application Security Project), and many curated threat collections and descriptions available on GitHub and other publicly-available repositories.

The good news, however, is that although charts like the ATT&CK matrices can teach you a lot of convenient terminology for threats, and teach you where and how to look for them in your network and in your logs:

Qilin and Rhysida gangs, for example, and you can help to prevent ransomware with the same tools and techniques that will also head off most other sorts of malware. Indeed, many ransomware attacks don’t start with a ransomware gang, but arrive at the end of a chain of previous intruders and attackers.Get in touch today, and let us help you improve your security posture fast.

Learn more about our mobile security solution that goes beyond traditional MDM (mobile device management) software, and offers active on-device protection that’s more like the EDR (endpoint detection and response) tools you are used to on laptops, desktops and servers:

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

Featured image of red roses by Biel Morro via Unsplash.

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.