Even if you’ve got cybersecurity covered in your own digital life, remember that friends don’t let friends get scammed!

We’re halfway through October already, which means we’re halfway through Cybersecurity Awareness Month, an initiative of the US government aimed at getting us all to do exactly what the name suggests.

Attitudes to Cybersecurity Awareness Month are, to put it bluntly, mixed.

Privately, you’ve probably heard experts you know and otherwise trust treating it superciliously, looking down on it as “too little, too late,” or treating it as some kind of “same old, same old” government formula showing that the authorities have fallen behind, and are happy clutching at trivialities instead.

Publicly, however, you’ve probably seen just how excited the marketing departments of cybersecurity vendors get about hitching their boats to the text Cybersecurity Awareness Month, if you judge by the number of paid or sponsored links your favorite search engine has recently been showing you if you search for exactly those words.

In the words of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, better known as CISA:

“Over the years, [Cybersecurity Awareness Month] has grown into a collaborative effort between government and industry to enhance cybersecurity awareness, encourage actions by the public to reduce online risk, and generate discussion on cyber threats on a national and global scale.”

If you keep up with cybersecurity news, you’d be forgiven for assuming that ‘cyber threats on a global scale’ inevitably involve what are known in the jargon as advanced persistent threats (APTs) from so-called nation-state attackers or state-sponsored actors.

The term ‘state-sponsored actors’ in this context doesn’t refer to students of film and drama who are attending government-funded schools or colleges. It is a metaphorical term for cybercriminals who work for, or who are in some way associated with, the government of a country. Those who are not obviously or officially on the government’s payroll may nevertheless avoid investigation or prosecution, and may be able to keep and even to flaunt their ill-gotten gains, apparently without attracting the attention of their local financial authorities.

As we’ve pointed out in numerous previous articles, almost all cybercrime is global in nature, and largely unaffected by international borders.

Even in countries with strict internal censorship or network restrictions, cybercriminals inside those countries can comparatively easily prey on victims outside their country (whether those criminals are ‘state-sponsored’ or not), and cybercriminals outside those countries can target victims inside them.

Cloud services make it easy for anyone who is (or who can pretend to be) in one part of the world to set up a fast and efficient online presence such as a web server or a blogging site, perhaps for just a few dollars, that can be accessed by visitors from almost anywhere else on the planet.

These cloud services often come with a domain name of your choice plus an HTTPS certificate that’s created for you automatically to give the site an aura of proper security.

Sometimes, hosted websites may even be available for a promotional ‘try-before-you-buy’ period that makes the service free if you decide to cancel your account within a day or two.

Sadly, a day or two is more than enough for cybercriminals to conduct a scam campaign that presents a realistic-looking but bogus login page masquerading as a well-known site such as a webmail service, a file-sharing utility, a payroll system, and so on.

In many cases where I have analyzed phishing emails that link to malicious websites, the domain names used for those lookalike sites had been allocated by a domain registrar for the first time earlier the same day, or late the previous evening, ready for immediate use by the cybercriminals who registered them.

The fake domain names used for cybercrime are often surprisingly realistic, as in the case of a scam I wrote about last year in which a malware-tainted WordPress plugin was distributed via the legitimate-looking domain en-gb-wordpress.org, which wasn’t considered misleading enough to be denied registration, despite its obvious similarity to the official name en-gb.wordpress.org.

As you know, phishing sites of this sort aim to lure impatient or incautious users to enter their login details, often including their username, password and current multi-factor authentication (MFA) code, into a web form that gets transmitted directly to the criminals.

Those criminals generally re-use the personal data they just harvested as quickly as they can, either using software to automate the process, or by having humans on standby in a ‘service center’ to work their way past any anti-automation tools that the genuine site might use to detect inauthentic logins.

If the criminals do catch you off-guard and get into your account without you spotting the subterfuge, they then have numerous lines of attack open to them, including:

Troublingly, getting started as a cybercriminal who phishes for passwords and then sells them online requires very little technical knowledge or skill, so that almost anyone can do it.

As we mentioned above, a ready-to-go web server with a domain name and a security certificate can be purchased in a few minutes for a few dollars.

And Github, for example, hosts several free, open-source tools, created ‘for research purposes’, that almost entirely automate the process of creating a realistic but evil copy of a legitimate site.

These click-to-phish tools generally include features including: automatically cloning the content of a third-party site to create a pixel-perfect replica; inserting booby traps into the fake site to to harvest any uploaded data; forwarding visitors to the real site after the phish to increase realism; generating scam emails for a list of targeted users, each with a uniquely trackable link; and providing a ‘campaign dashboard’ for viewing who clicked through and what personal data they gave away in the process.

In the screenshots below, I used a popular phishing ‘research toolkit’, downloadable from GitHub in ready-to-run form, to clone the Hire me to write for you page of my own website, complete with a web form that captures details from prospective customers.

The entire process, including downloading the software, cloning the page, generating a scam email template, ‘spamming’ it out to myself (the software allows CSV lists with any number of victim recipients to be imported), automatically hosting and serving up the fake page, and retrieving the stolen data via the dashboard, as shown below, took about five minutes.

From here, setting up as an Initial Access Broker is as easy as creating an anonymous account on an underground forum.

Some of these forums have been active for up to 20 years, and can be found with search engines on the regular web, thanks to front-end sites that operate in plain sight.

These publicly visible sites often present an illusion of legitimacy by publishing real-world cybersecurity news or offering genuine-looking services, but also provide handy dark web links that visitors can use with the Tor browser to teleport anonymously from the regular site to its underworld counterpart.

Here’s a long-running example, showing a cybercrime brokerage site with a main page on the regular web, offering Новости (news), Контакты (contact), Форум (forum), TOR (teleport to the dark web site), and Хранилище (storage):

The storage link provide a free cloud-based file sharing service, with an English-language front-end that almost mockingly warns you to “make sure you trust your recipient when sharing sensitive data”:

Initial Access Brokers don’t just sell passwords, but also traffic in ‘attack directories’ that provide ready-to-use lists of unpatched servers with the corresponding exploitable vulnerability for breaking into each one.

Just as with phishing, numerous open-source toolkits exist that make it easy for anyone with a fast network connection, or with a bunch of innocent computers that they control remotely via malware they implanted earlier, to scour the internet for vulnerable servers.

These tools automatically find and keep a record of servers that are open for business, but not yet patched against security holes that are exploitable using already-known vulnerabilities.

In other words, attackers such as ransomware criminals or data thieves (and remember that many contemporary ransomware criminals steal data immediately before they scramble files in order to double up on their blackmail leverage) don’t need to spend their own time, or to risk giving themselves away, in order to acquire a list of prospective victims.

Some data-stealing and ransomware attacks are targeted very specifically, with the attackers deciding in advance that they are going to go after government department X or global business Y, and then explicitly buying up or finding for themselves a way into those exact organizations.

In other cases, attacks may be targeted much more loosely, with criminals buying up a list of vulnerable networks in a general category, such as ‘companies with 200 to 2000 Windows computers that rely on online sales’ or ‘hospitals with Accident & Emergency departments in major cities’, and then picking off victims from their shortlist one by one.

The publicity-grabbing ‘nation-state attackers’ and ‘state-sponsored actors’ we mentioned at the top of the article do exist, and represent a clear and present danger to our cybersecurity.

But the underlying message from everything we’ve talked about so far is that these so-called ‘advanced’ attackers are not the only danger we face, and probably aren’t even the primary threat we should be addressing.

The precautions promoted by Cybersecurity Awareness Month 2024, in its 21st annual incarnation, may feel as though they are old-fashioned, and obvious, and unexciting, and even unimaginative…

…but they are nevertheless profoundly important, because it is vital that none of us balk at the basics.

Blunders relating to phishing, passwords and patching are still the major underlying cause of the ever-expanding number of serious data breaches.

Fortunately, as CISA’s own social media tiles remind us, the basics are surprisingly easy to remember:

CAPS, and at least 1 digit, and a few $%^* wacky characters. Use that sort of trick if you like, but blindly obeying those complexity rules can lead to predictably weak passwords like P4ssWord! being judged stronger than a genuinely random choice such as RNTUMNSSXHINRVZZMAKUMOUKYXQKANXQ.We still haven’t collectively built a cybersecurity culture in which we routinely Get The Basics Right.

So why not use Cybersecurity Awareness Month 2024 as a reason to set that as a goal to aim for in the year ahead?

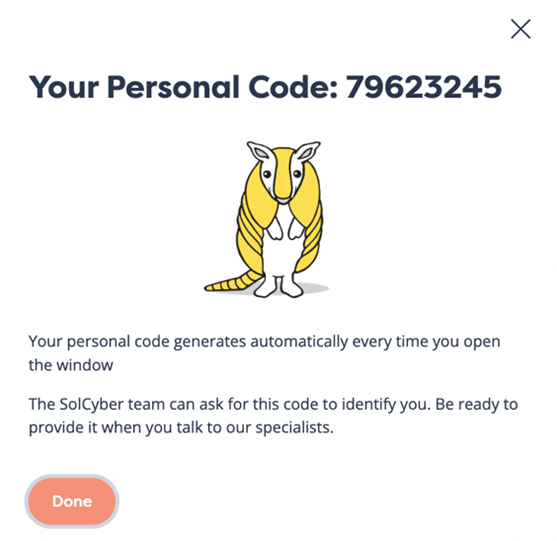

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.