Fighting fake content – How you can help

Cybersecurity snake-oil – it’s high time we put a stop to it!

If the media player above doesn’t work in your browser,

try clicking here to listen in a new browser tab.

Find TALES FROM THE SOC on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Spotify, Podbean, or via our RSS feed if you use your own audio app. Or download this episode as an MP3 file and listen offline in any audio or video player.

[FX: PHONE DIALS]

[FX: PHONE RINGS, PICKS UP]

ETHEREAL VOICE. Hello, caller.

Get ready for TALES FROM THE SOC.

[FX: DRAMATIC CHORD]

DUCK. Welcome back, everybody, to TALES FROM THE SOC.

I’m Paul Ducklin, joined by David Emerson, CTO and Head of Operations at SolCyber.

Hello, David.

DAVID. Hey there.

DUCK. A potentially controversial/rant-strewn episode this month, David!

Let’s hope neither of us get too carried away, because I know we both feel quite strongly about this issue.

The title is: Fighting fake content – how you can help.

There seems to be more fake cybersecurity nonsense than ever on social media sites, LinkedIn being just one of several examples, where people are being pitched security solutions that they don’t need, because that threat died out 10 years ago.

And all they’re doing is distracting themselves from doing things that really could help.

So, how do you prevent yourself from falling into scams and malware treachery?

How do you protect your colleagues, friends and family if you think they’re at risk?

How do we pressurize content sellers for higher standards?

And how do we push vendors and so-called experts to sell more on truth and less on fear, uncertainty, and doubt?

DAVID. [LAUGHING] I like how you promised everyone a rant up front․․․

[LOUD LAUGHTER]

A lot of these are deliberate dishonesty, and a lot of them are *profitable* deliberate dishonesty,

And I think that they essentially consist of a vendor or an entity (it’s not necessarily always a vendor, but I think, more often than not, that’s who benefits)․․․

They basically are going to pick some kind of profitable conclusion.

They’re going to then subsequently kind of invent a hypothesis that, if true, would justify that conclusion.

And then they’re going to backfill, with fake authority, what it is that they’re proposing.

“Coffeeshop Wi-Fi is middled,” for example.

With WPA3 and modern standards, it’s not impossible, but it’s highly unlikely, and it probably isn’t how you’re losing your information.

And neither is a VPN an invisibility cloak.

DUCK. Yes.

DAVID. But if those things were true, you could easily have a sort-of expert authority filling that void created by the logical dissonance of, “Coffeeshops exist. They have convenient Wi-Fi, and I need to get something done. So how do I do anything?”

And that’s the opportunity to sell.

I blame this mostly on vendors, and on the profitability of essentially inventing that deliberately dishonest information.

DUCK. So, what can consumers, and companies, for that matter, do to get more access to the truth, and to be less distracted by advice that isn’t the magic bullet that’s promised?

What should we be doing to push back against this kind of “FUDification”?

DAVID. The number one thing that we can do lies within us, and it is *critical thinking*.

Cybersecurity is complex; no one likes complexity.

People want definitive answers, and easy fixes, and guarantees that don’t exist.

And that demand creates the market for this nonsense.

As long as the public prefers comforting fiction over inconvenient reality, these vendors are just never going to run out of customers.

So, step one, look within yourself.

Critically analyze the things that you are being told.

I think that some of that is beyond some people’s ability, because it’s hard to know, for some people, that WPA3 has more or less obviated our concern for coffeeshop Wi-Fi.

DUCK. And HTTPS in almost every browser connection we use these days.

DAVID. Right.

Some people might not realize how boring it is to sniff a public network at this point.

DUCK. [LAUGHS] Yes!

DAVID. I mean, it really is.

It isn’t hard, though, to expect certain things in the information that you’re being given.

It isn’t hard to sniff out transparency.

The likelihood that a product solves 90% of all kinds of attacks is of low likelihood, so use your critical thinking, even if you don’t know what those attacks are.

Ask the vendor what they actually *do*, not what their marketing implies.

Realistic threat models – that isn’t something that’s beyond your reach, either.

Most people don’t need nation-state defenses; what they need is to stop clicking phishing emails and running unpatched software.

I guess that’s why I say it’s almost a critical thinking matter, right?

If you really believe that anyone’s after you․․․

․․․do the basics!

And then there are other things that people can do, as well, that fall into this sort of critical thinking.

Layered defenses.

That’s a concept that almost everyone can understand, even if they don’t necessarily know what those specific defenses are.

Defense in depth actually does work; any single miracle tool probably doesn’t, for numerous reasons.

So, this trope of the ‘silver bullet,’ or the modern paradigm of the consolidated tool stack?

It’s unlikely to be the best at all of the things it does.

And people can detect a company that is overselling its functionality, because a tool that is a ‘silver bullet’ probably is less competent than an aggregate of other tools, or other procedures, that would be more pragmatic.

DUCK. So what do you have to say about what you might call a counter-argument, namely that individuals, consumers, can’t be expected to sniff this stuff out.

Because, hey, even some of the biggest and wealthiest institutional investors in the world fell for Elizabeth Holmes (now serving, what is it, 11 years in prison?), and Theranos.

This whole idea that, “We’ve come up with a whole new way of doing blood tests,” and we’re going to, if you like, confect the science or the research that makes it look as though it works.

Didn’t Walgreens even get drawn into that, to the point that they were going to start installing these machines in their pharmacies as part of a public-facing service that people were supposed to trust?

DAVID. Well, the Theranos idea as a grift․․․

DUCK. [LOUD LAUGHTER] Yes.

DAVID. I mean, that’s what it was, right?

You start by assuming that the miracle exists, and then you kind of, I don’t know, market like hell until people believe that it does.

And you see that in cybersecurity, too.

I think that, thankfully, you see it on things that are more obviously unlikely.

I don’t know that the average person on the street could be expected to know that a drop of blood is simply not enough blood to perform the number of labs [LABORATORY TESTS] that Theranos was purportedly performing on that drop of blood.

DUCK. Yes, I guess the average person does have a computer at home; they do have a mobile phone; they do know roughly what a phishing attack is.

But they probably have never worked with a gas chromatograph, for example.

DAVID. Yes, that’s exactly my point.

There are some people in the general population․․․

In fact, I’m going in to get labs done in January, and I’m doing one of those panels [OF MANY DIFFERENT TESTS] where it’s just everything.

Everything – I’m going to have 16 vials of blood drawn!

I am going to be a different-sized creature by the time they’re finished with me, it sounds like.

DUCK. The thing I love about this bloodletting, when you need those kind of tests, is the job title of the person who takes the blood from you, which is phlebotomist.

DAVID. [LAUGHS] They know all the tricks; they know all the misdirection; all the needle insertion angles.

Yes, they know how to do it!

DUCK. And practice definitely makes perfect.

DAVID. I actually can see why the Theranos grift is harder to detect.

Because you’re picking information that is just very difficult to relate to for the average person.

Somebody who had just done a giant bloodletting in order to get a giant panel of results would be able to say, “No, actually, there’s a reason I gave 16 vials of blood.”

Because it went off to five different labs, and it becomes obvious pretty quickly that a drop isn’t going to cut it.

But the average person at most has given one or two, and maybe never, and that would be a hard claim to evaluate.

The cybersecurity realm, thankfully, really isn’t that sophisticated, actually.

It’s not that much of an unverifiable claim.

And so, people can start doing things like self-regulating – not sharing things just because they sound spicy, but checking for evidence first.

That’s entirely possible in a way that may be a little bit harder to do with a drop of blood.

In cybersecurity, we *do* have a sense of what you should be doing in the workplace, and it’s not clicking on emails that ask you to buy gift cards.

That’s a pretty relatable, simple thing.

DUCK. With cybersecurity, you can help your friends and family; you can help your colleagues.

We can look out for each other, and avoid what I think you’ve referred to as the “tragedy of the commons.”

That’s where people suddenly aren’t looking out for one another, because it’s easier not to, and just to go with the popular view (or the populist view) that pops up on social media.

Would you agree with that?

DAVID. Yes.

It’s also because the signal-to-noise ratio has gotten so skewed that any amount of pushback, or any amount of calling out this phenomenon, is at best ineffectual, if not entirely lost in the discussion.

DUCK. Yes.

DAVID. There are so many simplified narratives out there that are easily called out, or so many fear-based marketing campaigns that are easily called out, that many people would know are total BS.

DUCK. There’s also the problem, isn’t there, that I’ve heard from very many people when I’ve tried to fight back on social media about claims that are either specious or, to my mind, clearly fraudulent․․․

They’re aiming to get somebody to spend money that they don’t need to spend, and more importantly (because it’s often only a modest amount of money) will *not* provide the protection they think.

The problem is that people say, “Yes, but what’s the harm in advising my buddies to spend $22 on a fancy USB cable that *might* protect them, and probably won’t do any harm?”

DAVID. Yes, it feeds into so many rather menacing constructs, like over-consumption and snake-oil.

We’re not the only industry, we’re not even close to the only industry – it runs the gamut from household appliances to audio equipment.

DUCK. [LAUGHING] Do you remember those special pens to write around the edge of a CD, that stopped the light escaping?

DAVID. [AMUSED DISMAY] Oh God, no.

DUCK. Oh dear, yes.

DAVID. I don’t doubt it.

The audiophile community is baffling․․․

DUCK. [MOCK ALARM] $25,000 amplifiers!

DAVID. Yes, it’s crazy.

The whole thing is a menace.

I actually like good audio gear a lot, and I’m also super-distressed by what is sold as good audio gear, and the under-emphasis, the de-emphasis even, of truth.

DUCK. And for the money that they charge, you could buy a top-end digital oscilloscope and measure it all for yourself, which would be much more fun.

DAVID. Yes.

DUCK. *And* a gas chromatograph! [LAUGHTER]

DAVID. Yes, so you could test the claims of Theranos *and* the claims of Pass Labs all at once. [LAUGHS]

DUCK. I’ve looked on eBay and you can get decent second-hand gas chromatographs between about £1000 and £2000. [ABOUT $1300 TO $2600]

DAVID. Oh, that’s information I didn’t need to know.

[WORRIED BY TEMPTATION] Oh dear.

DUCK. The only hassle is, “Owner must collect.” [LAUGHS]

DAVID. [BRIGHTENING MOOD] Yes, that might save me a bit.

If it’s in the middle of North Carolina, and I have to drive seven hours, there’s no way.

DUCK. Yes, you’re not the first person I’ve mentioned that to who’s gone, “Hey, that’s an *idea*,” when I intended it as a joke.

DAVID. Yeah, actually, there’s kind of a sidebar – but CNC machines are the same way.

You would be shocked at how inexpensive CNC machines and lathes, like old-school metal lathes․․․

․․․they can be surprisingly inexpensive, as long as you’re willing to tow a 6000lb object somehow. [2700KG, OR 2.7 TONNES]

DUCK. Yes.

So maybe we shouldn’t be so surprised that people go, “Well, I’ll spend money on things that might help, and probably won’t do any harm.”

But when it comes to cybersecurity, as we’ve established, they *can* do harm because they’re sort of informing you of all these things that you think are protecting you, where in fact you have mitigated your risk not one jot.

DAVID. They do harm in the cybersecurity realm – the culture of over-consumption; the culture of quick fixes.

That is fundamentally the harm.

DUCK. Yes.

“More tools, more tools,” to quote Amos The Armadillo. [SOLCYBER’S LOVABLE MASCOT.]

DAVID. Yes, exactly.

I hate that we keep coming back to this, because it’s not the intent of the podcast, but it is absolutely true.

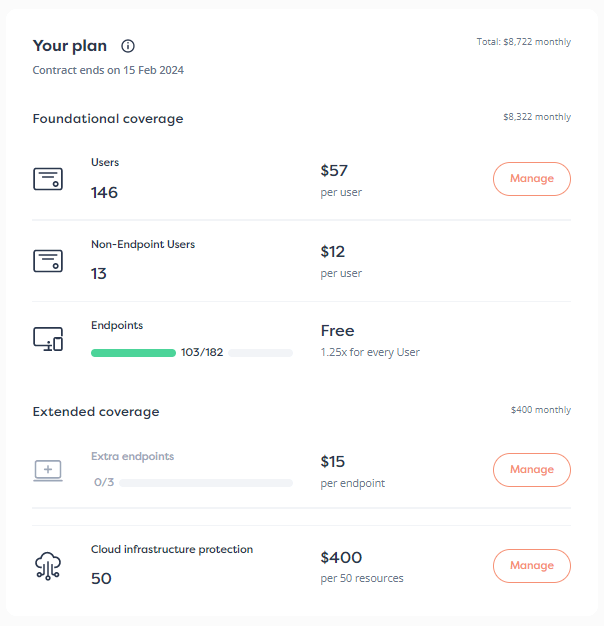

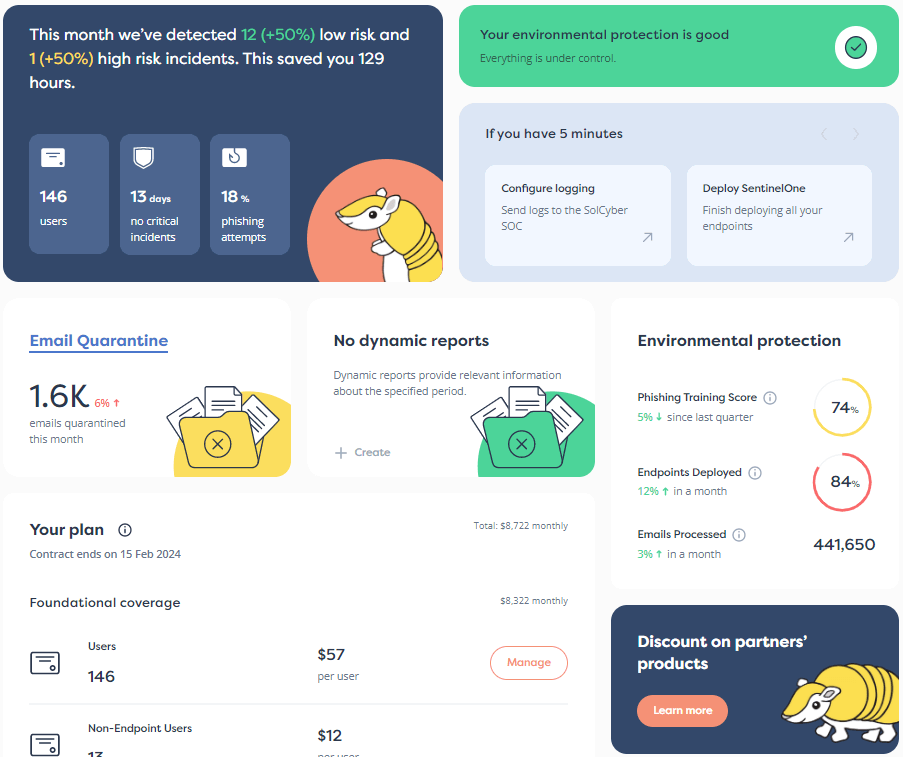

There’s a reason SolCyber’s marketing looks like it does.

Because it’s an unhealthy construct where you just “buy *something* and that fixes *everything*.”

It’s not how things work.

How things work is actually much more humane, and social, and expert based than any given automation or tool just plugging away at an esoteric problem that is likely not your problem.

DUCK. So David, how much pressure should be brought to bear on social media platforms to control, or to regulate, or to prevent this fake science from being taken seriously?

Now, I know they like to fall back on First Amendment stuff, and “It’s free speech,” but free speech doesn’t mean they’re allowed to get away with it.

Today, when we’re supposed to have higher cybersecurity standards, it’s easier than ever for rogues, and cybercriminals, and state-sponsored actors, and tricksters to publish content that not only doesn’t get regulated, but actually ends up making money for the people who are hosting it.

So what should we be doing about that?

Is there something we can do to make those organizations a bit more accountable?

DAVID. Yes.

[LAUGHS]. But I like your invocation of the word ‘trickster.’

That’s exactly how I imagine most of these people on the other end of these attacks.

In the 1990s, that was happening, but in the 1890s, people were drinking motor oil in the hopes that it would solve their leprosy.

And that kind of snake-oil mentality was overcome with a culture of empirical skepticism.

Say what you will about what’s happening acutely․․․ for the most part, the long-term trend is that people believe medical science.

And people believe some of the regulatory bodies that have cropped up around medical science, such that we are no longer permitting, really, or at least no longer as vulnerable to (where it is permitted), the marketing of false cures.

DUCK. And that really started in the 1960s, didn’t it, when the FDA said, “You know what? Food labeling regulations? We are going to make you tell the truth about the ingredients that are in your product.”

So that if somebody actually wants to check, they have some chance of doing so, and you’re not allowed to put in stuff that you don’t declare.

DAVID. It’s very specific to an industry, but if you look at what happened prior to that, it isn’t to say that all cures for all things prior to that were falsehood.

There absolutely were some products that did something, maybe even that did something that would be impressive in a modern sense.

But the reality is the market was deciding.

People were saying, “OK, well, I don’t believe *this* snake oil. I’m going to buy *that* snake oil.”

And so I think that we are essentially, in the cybersecurity industry, prior to that regulatory pinch-point from which everything else will expand again into a trustworthy paradigm.

I think that people have to not only expect there to be some governance around the marketing of these things, but also, culturally, we need to build an empirical culture of awareness and critical thinking about whether or not something really is what we want to ingest․․․ or buy, in the case of a cybersecurity product.

DUCK. So you’re saying we basically need a 21st century Age of Enlightenment all over again?

DAVID. Yes, but specific to the industry.

[LAUGHTER]

And the industry does need to recognize that it’s really squandering resources, across the board, for the limited benefit of a few.

This is not unique to cybersecurity, but it’s a hot topic that concerns us and actually does concern many of our customers.

DUCK. Yes.

DAVID. These vendors need to be called out on their BS.

They need to be called out on their narratives which are fear-based.

And we need to, likewise, at the same time reward vendors – largely with profits and purchases – that explain those trade-offs.

Those that give a balanced view of what they can do, what they can’t do, what you should be doing, and who your attackers are, rather than just, “We solve 90% of attacks, and nation-states are after you.”

The cybersecurity industry, because it is more fertile ground, has chosen the approach of fear.

We’ve chosen to put people in this mood of fear and aversion, and then to exploit that mood of fear and aversion.

DUCK. Do you think that it just boils down to voting with your checkbook?

Is it really that simple?

Favor cybersecurity companies that are not averse to the truth; that sell you things on the basis of what they can probably do for you; and more importantly, how they can help you achieve the results you want?

Instead of favoring those who publish reports that, as you say, confect the hypothesis that just happens to come to the conclusion they want?

DAVID. I do think that at a personal level, it comes down to: checkbook; critical thinking; culture of aversion to comforting fictions.

So I think, at a personal level, that’s about what you can expect.

Outside of the personal level, I do think that there’s a role for governance and regulation here.

“Truth in advertising,” let’s say.

And we don’t really see a lot of that in the software industry.

I don’t have a ton of hope that it’s coming anytime soon․․․

․․․but it’s something that is worth calling out.

It has been successful in the past in life-critical sorts of industries, like medicine.

And I think cybersecurity could be, in some contexts, a life-critical sort of industry.

DUCK. Well, cybersecurity (or perhaps I mean cyber-insecurity) can certainly cause what are effectively life-changing injuries, if you like, even after apparently minor attacks.

If you think of individuals who lose sufficient money from their savings that the rest of their life is in turmoil.

DAVID. Right.

DUCK. Folks who have a permanent wedge driven between them and their family, because the cybercriminals benefit from the fact that they keep things secret.

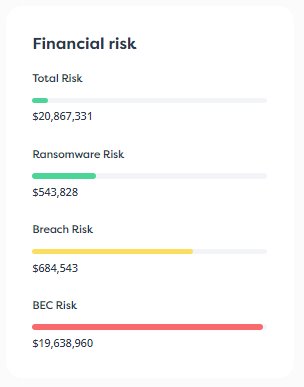

Or businesses that go bust because some simple precautions could have prevented either a ransomware attack or a business email compromise attack, or something like that, where basically money went south and there’s no realistic hope of getting it back.

DAVID. Yes.

DUCK. David, I’m conscious of time.

So, if I ask you to come up with two or three tips that people can provide, as we said at the beginning, to protect themselves; to protect their friends and family if they think they are vulnerable; and to promote companies that tend to tell the truth, rather than FUD․․․

․․․what would they be?

DAVID. Well, we’d start with, “The truth is harder to explain than fiction.”

So, analyze the things that you’re being bombarded with.

If you’re in the position of being consulted by your friends and family and whatnot, remember your place in the social order of protection, because social protection is real.

DUCK. Yes.

DAVID. Keep in mind that you are part of this defense in depth that I’m talking about.

DUCK. Absolutely.

And so many technologists in cybersecurity want us to forget that, don’t they?

“Oh, AI will solve it, or the automated tools will solve it, or 72 layers of this behavior-blocking protection will solve it.”

DAVID. Yes.

DUCK. Although all of those things help, and help significantly, at the end of the day, it’s still the human context and the human involvement that really helps, and provides us with the most vigorous final defense.

Would you agree with that?

DAVID. Yes, I absolutely would agree with that.

Sometimes SentinelOne, for example, won’t stop something – it’s not perfect; no system is.

And then, what stops the thing is the vigilance of the people around you.

That will be occasionally called into question with, “Oh, well, SentinelOne didn’t stop that one thing that we then had to manually remediate. What good is it anywhere? Let’s rip it all out. Let’s stop paying SentinelOne.”

DUCK. Yes, and then some other vendor might come along and say, “Hey, well, try our product against that particular threat,” because they happen to know in advance what the result will be.

DAVID. Right.

DUCK. They use that as a slightly devious way of convincing you that the other product is superior.

When in fact, you may be talking about the difference, in an automotive analogy, between 8.3 liters/100km and 8.25 liters/100 km. [28.34 MPG (US) AND 28.51 MPG (US)]

DAVID. Yes.

DUCK. In practical terms, no significant difference at all.

DAVID. Yes, and it’s important to remember that’s the case.

Because that allows the acceptance of that kind of marketing, which allows vendors to drive a wedge between you and the products that you presently use with this assertion that there’s greener grass and lower payroll counts on the other side.

That just isn’t the case.

Social protection is real.

It’s part of defense in depth.

And all products have their limits, and they are also part of defense in depth.

I just think that those are probably the main takeaways for people who are in a position of being consulted.

DUCK. Look before you leap.

Think before you act.

And don’t begrudge your friends and family the help that they may need, even if it’s hard to convince them.

Because as you say, sometimes the truth is harder to explain than fiction, or fantasy, or lies.

Don’t give up, because we can surely get there in the end if we all pull in the same direction!

DAVID. Don’t give up. [LAUGHS]

Life goes on, no matter what you try to do.

DUCK. [LAUGHING] Indeed!

David, thank you so much for your time.

I don’t think this came out as too ranty.

I think we were reasonably critical of the industry of which we are part, but we’re certainly at a point where just spending more money on tools and automation, and waiting for the machines to fix it all․․․

․․․is clearly not going to have the results we really need.

Thanks to everybody who tuned in and listened.

Please subscribe to the podcast; that way you’ll know when each new episode drops.

Please also visit solcyber.com/blog, where you will find very little sales schpiel, and a lot of community-focused advice that can help you, your friends, your family, your colleagues and your company.

So once again, thanks for listening, and․․․

Until next time, stay secure.

[FX: CALL ENDS]

Catch up now, or subscribe to find out about new episodes as soon as they come out. Find us on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Spotify, Podbean, or via our RSS feed if you use your own audio app.

Learn more about our mobile security solution that goes beyond traditional MDM (mobile device management) software, and offers active on-device protection that’s more like the EDR (endpoint detection and response) tools you are used to on laptops, desktops and servers:

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.