Remember the WannaCry virus, which took the world by surprise just over eight years ago?

Very swiftly summarized, the story goes something like this:

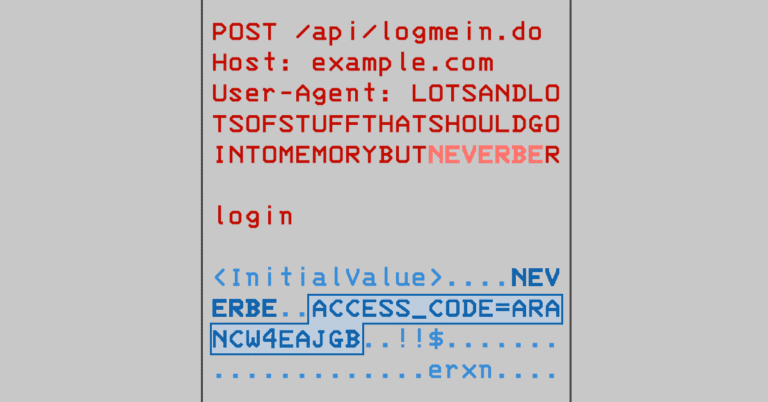

ETERNALBLUE. Microsoft became aware of this bug, among others, and quietly patched against it in the March 2017 Patch Tuesday. Sysadmins who updated promptly therefore immunized themselves against future abuse of this vulnerability.ETERNALBLUE to spread itself automatically on and between Windows networks.By very good fortune, a British cybersecurity researcher spotted an as-yet-unregistered internet domain name that the virus code tried to contact, and quickly registered it, hoping to prevent the attackers from using it later on as a command-and-control channel to implant new malware, a common malware scenario then and now.

(Controlling a malware domain and thereby actively capturing any call-home activity can also provide actionable insight into the prevalence and distribution of that malware.)

In fact, this special domain name had been coded into the worm as an emergency “kill switch,” perhaps so that the worm operators could turn the malware off abruptly if it spread so far and fast that it backfired and started harming the attackers themselves.

The fortuitous activation of the kill switch certainly made the damage done by WannaCry much less dramatic that it would otherwise have been, but even in the short time window during which it was able to spread unnoticed and unregulated, it is estimated to have hit more than 200,000 computers across the globe.

The British National Health Service (NHS), one of the world’s biggest employers, was particularly badly hit, with non-emergency health care affected; other victims apparently included the German railway network, French automotive factories, Spanish telecommunications companies, and service stations in China.

The malware outbreak, and the risk of subsequent attacks using the same exploit, was sufficiently severe that Microsoft followed up its Patch Tuesday updates by publicly releasing patches for old, out-of-support Windows versions, including Windows XP.

Even eight years ago, you might have hoped that IT teams with any sense of malware history and cybersecurity risk would make sure they rolled out patches for critical remote code execution (RCE) vulnerabilities within two months.

Unauthenticated RCE bugs that work at the network packet level – such that almost any user within “network reach” of an at-risk computer can trigger the bug without needing to login or to show their hand first – are well-known to be high-risk vulnerabilities.

If you’re a LinkedIn user and you’re not yet following @SolCyber, do so now to keep up with the delightfully useful Amos The Armadillo’s Almanac series. SolCyber’s lovable mascot Amos provides regular, amusing, and easy-to-digest explanations of cybersecurity jargon, from MiTMs and IDSes to DDoSes and RCEs.

Even if you know all the jargon yourself, Amos will help you explain it to colleagues, friends, and family in an unpretentious, unintimidating way.

Anyone who has read anything about super-quick network spreading malware of the past, such the Morris worm of 1998 or the Slammer worm of 2003, will know that unauthenticated network RCE bugs have frequently been associated not merely with intrusions, but with so-called wormable exploits.

A wormable exploit means that a system, once attacked, can automatically be turned against other vulnerable systems to spread the attack further, typically without further human intervention.

As it happens, self-spreading malware of this sort is unusual these days, not least because it generally draws more attention to itself than it needs to.

Wormified or not, however, unauthenticated network-based exploits that lead to RCE or to unauthorized access are still a favored vehicle for attackers, especially if the exploit exists in a device that is directly exposed to the internet on purpose, such as a web server, a VPN access point, or a network security firewall.

With this in mind, therefore, it’s disappointing to see articles such as a recently-updated warning from the Dutch National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) about attacks involving various vulnerabilities in Citrix NetScaler products that were identified and patched back in June 2025.

Reports suggest that the security holes CVE-2025-5777 and CVE-2025-6543 can be used against NetScaler ADC and NetScaler Gateway products as a stepping stone to break into unpatched networks.

Between them, these vulnerabilities apparently allow unauthenticated outsiders to steal existing authentication credentials and to run untrusted code without any credentials.

This is a considerable security risk given that NetScaler Gateway devices are meant to be exposed to the internet, and may even act as a primary access control mechanism (a VPN, or virtual private network), the first port of call, for remote users.

It’s fair to criticize vendors for having bugs of this sort in the first place.

But be careful that your own customers don’t get a chance to criticize you in turn if you’re still vulnerable long after the vendor has disclosed, warned you about, and patched security holes of this sort.

The lessons from this anecdote are simple:

Why not ask how SolCyber can help you do cybersecurity in the most human-friendly way? Don’t get stuck behind an ever-expanding convoy of security tools that leave you at the whim of policies and procedures that are dictated by the tools, even though they don’t suit your IT team, your colleagues, or your customers!

Paul Ducklin is a respected expert with more than 30 years of experience as a programmer, reverser, researcher and educator in the cybersecurity industry. Duck, as he is known, is also a globally respected writer, presenter and podcaster with an unmatched knack for explaining even the most complex technical issues in plain English. Read, learn, enjoy!

By subscribing you agree to our Privacy Policy and provide consent to receive updates from our company.